|

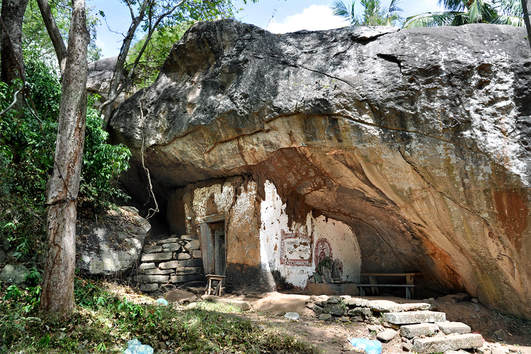

a less-kown large excavation site in the Deep South of Sri Lanka - not far from Tangalle Though it is situated at the A18 main road, which is connecting the southern beach resorts such as Tangalle and Kirinda with the "elephant national park" Udawalawe and the "gem city" Ratnapura, the Rambha Viharaya (also transcribed "Ramba Vihara") is rarely visited by foreign travellers. To be honest, this archaeological site is not as amazing as the nearby rock and cave temple of Mulgirigala. And Situlpawwa in the Yala area might earn the fame of being a more fascinating ancient site, just due to its environmental settings. However the Rambha Viharaya is one of the largest excavated temple complexes in the southern plains of Sri Lanka, although not many Sri Lankans and foreign guests seem to be aware of this fact. What is now called the Rambha Viharaya once served as the main monastery of an ancient city named Mahanagakula, which was an important trading center in antiquity and became the capital of Sri Lanka's Deep South during the Polonnaruwa period. Even the nation's famous Tooth Relic is said to have been kept here for a while during the period of Indian Chola hegemony over the northern half of the island. The reputation of the "banana monastery" - which actually the literal meaning of "Rambha Viharaya" - remained to be far-reaching after the Polonnaruwa period, when even monks from Myanmar's world-famous temple-town Bagan sought advice from the monks residing here in southern Sri Lanka.

0 Comments

The ruins of the Barandi Kovil in a suburb of Seethawaka (formerly known as Avissawella) are rarely visited by foreigners, though many travel along the close-by main road from Kitulgala to the coast. To be honest, what can be seen of the former state temple of the 16th century is not quite imposing. However, the Barandi Kovil archaeological site is worth a short break, as the location is quite charming and the temple is of some historical significance, as it was the main building of the former Seethawaka kingdom, which was the most important principality of the island in the second half of the 16th century. Furthermore, this is the only major state temple of a Sri Lankan monarchy that was dedicated to Shiva and thereby Hindu instead of Buddhist. Actually, Hinduism seems to have replaced Buddhism as the Sinhalese state religion in the Seethwaka period. This is the reason why the Seethawaka kingdom, though the major proponent of Sinhalese independence against Portuguese overlordship, has not a good reputation in Buddhist historiography.

Learn more about the Barandi Kovil of Seethwaka here... The north gate of the 20th century main temple in Kelaniya is flanked by quite spectacular Gajasimha sculptures. Gajasimhas are hybrid anmimals, a lion's body is depicted with the head of an elephant. Gajasminhas do not play a role in Hindu mythology. Probably, they are not a twist of the Narasimha incarnation of Lord Vishnu, as this Avatar has a lion's head. Nonetheless, Gajasimhas are a quite common sight at historical temples of southern India. Gajasimhas signify strength and sovereignty, particularly the might and wealth of a kingdom. Gajasimha sculptures are not known from Sri Lanka's Anuradhapura period, although some Indian specimens date back to the first millenium A.D. Gajasimhas are quite popular in the art of Southeast Asia in the second millennium. Depictions are found in Cambodia's Khmer temples in Banteay Srei and Roluos as well as in central Vietnam Cham culture and in various periods of Thai history. In Southeast Asia, Gajasimhas are portrayed as guardians of temples or as a mount for human warriors. In Sri Lanka, Gajasimhas are characteristic of the medieval Yapahuwa and Gampola periods.

Though Trincomalee is famous for the Koneshvaram Shiva Temple on the Swami Rock in the first place, there are some more Hindu temples of interest in the town. The largest one is devoted to Kali. In contrast to Vishnu, who is venerated by Sinhalese Buddhists and Tamil Hindus alike, worship of Kali is exclusively Tamil in Sri Lanka. Kali is the most powerful and violent form of Shakti, the female energy of male deities. She is venerated as destroyer of evil forces in the first place. But in Bengal, where tantric practices became dominant in the 7th to 9th century, Kali is held in high esteem as the mother of the universe, too. Kali plays a role in some Buddhist traditions, too, namely in Buddhist tantric schools, particularly in Nepal and Tibet. However, Kali is of no significance for Sinhalese devotees. Among Tamil temples in Sri Lanka, Kovils dedicated to Kali are not as common as those for her husband and sons, Ishvara (Shiva), Kataragama (Murugan) and Pilliyai (Ganesha). Most temples of the mighty and often furious Kali in Sri Lanka are dedicated to one of her more delightful incarnations, the helpful and curing Amman, known as Mariamman among Tamils.

The Kali temple in the very centre of Trincomalee is dededicated to Bhadrakali in particular. A separate Kovil for Ganesha is attached. The Kovil is built in the typical stlye of Dravidian architecture of south India. The most eye-striking feature of the Dravidian style is the large gatetower known as Gopuram, which is adorned with plenty of sculptures. Colourful sculptures of deitie and other celestial beings are fond in the interior of the Kovil, too. Just as in the case of Kataragama shrines, it is a comon practice of praying for needs by breaking coconuts in front of the temple oentrance. Access is allowed to foreigners, if they respect the local dress code. Pooja is celebrated trhee times a day, at 7.00am, 12.00 noon and 5.00 pm. Most locals venerate Kali n Tuesdays and Fridays in particular. The temple feast of this Kovil is usually the fortnight in the second half of March. Tamil temples in India and Sri Lanka are called Kovils. Both photos taken in Colombo show two characteristic features of Kovils, namely the gateway tower called Gopuram and the chariot called Ratha. Gateways carrying the highest towers are not found in temples in northern India. Gopurams have been a feature of Dravidian (Tamil) temples since the classical Pallava period and have surpassed the other temple towers (Shikharas) in height since the Nayak period of the early modern age.

In contrast to Gopurams, Rathas are actually not found at Tamil temples exclusively, Rathas are the cariots of temple feasts all over India. During the festival season, they are richly decorated and pulled through the streets. The name 'Ratha' is of Sanskrit origin and etymologically related to the Spanish word 'rueda', meaning 'wheel', and more obviously to the Latin and English term "radius", indicating a circular form. Though this may appear to be somewhat odd, the origin of Gopuram architecture is actually the Ratha. How can this be? Rathas are made of wood and Gopurams are stone buildings. However, the Pallava architecture of the 7th century imitated wooden chariots by stone constructions of almost the same shape and size, as can be seen at the famous Pancha Rathas ('Five Rathas') in World Heritage Site Mahabalipuram near Chennai in India's state of Tamil Nadu. Actually, these Pancha Rathas of the Narasimhavarman period of Pallava architecture, though not completed afterthe king's death, became prototypes of Tamil tower architecture in general - and in the course of the centuries their original shape developed into those giant towers known as Gopurams or Gopuras.

|

AuthorNuwan Chinthaka Gajanayaka, Categories

All

Archives

June 2020

Buddhism A-Z

|

|

Find a list of 270 Sri Lanka travel destinations & attractions: CLICK HERE Our illustrated list of places of interest is sorted by travel regions, more precisely: by 22 most recommendable places for overnight stays. All 270 sights are within day-trip distance from one of those 22 major locations. (Please understand: Loading 270 images requires more seconds than usual.) |

Why travel with Lanka Excursions Holidays?

+ We are a local agency owned and run by Sri Lankans, not part of international holdings

+ We are well known for our direct and personal relationships with travellers

+ We facilitate authentic meetings with locals who are not from the tourism sector

+ We follow a strict policy not to push guests to visit shops and shops and shops

+ We have an unrivalled expertise to show you places off the beaten path

+ We provide genuine information instead of clichés and tourism industry slogans

+ We are a local agency owned and run by Sri Lankans, not part of international holdings

+ We are well known for our direct and personal relationships with travellers

+ We facilitate authentic meetings with locals who are not from the tourism sector

+ We follow a strict policy not to push guests to visit shops and shops and shops

+ We have an unrivalled expertise to show you places off the beaten path

+ We provide genuine information instead of clichés and tourism industry slogans

Our ambition is to provide high-quality information in preparation of your Sri Lanka holidays

... and even more superb travel experiences

... and even more superb travel experiences

we also run our own guesthouse near Anuradhapura:

First House Mihintale

87, Missaka Mawatha, Mihintale 50300, Sri Lanka.

0094 71 6097795

87, Missaka Mawatha, Mihintale 50300, Sri Lanka.

0094 71 6097795

|

Lanka Excursions Holidays

Registration Number SLTDA/SQA/TA/02179

255/24, "Green Park" Dawatagahawatta, Thimbirigaskatuwa, Mahahunupitiya East, Negombo, Sri Lanka

Office: +94 31 223 991 Hotline: +94 71 6097795 [email protected] Lanka Excursions Holidays office hours 8.00 to 6.00 p.m. daily (except from June Fullmoon Day)

|

if not stated otherwise, texts and photos provided by Ernst A. Sundermann, sales manager of Lanka Excursions Holidays

all rights reserved, © 2016 Lanka Excursion Holidays

all rights reserved, © 2016 Lanka Excursion Holidays

RSS Feed

RSS Feed