The lonesome Buddhist Temple of Thambalagollewa in the remote northern part of Anuradhapura District is one of the sites almost never visited by foreign tourists, though it's a quaint place and of some historical importance. The temple is also known as Kuda Dambulu or Little Dambulla. However, it's not to be confused with the Kuda Dambulu Raja Maha Viharaya of Walahawiddawewa, which is situated 11 km (8 miles) further east, closer to Horowupotana.

Kuda Dambulu cave temple

The name Kuda Dambulu of the Thambalagollewa Temple refers to the existance of a cave shrine decorated in the typical Kandyan style. The small cabe has a Buddha statue in Samadhi Mudra, flanked on either side by two standing sculptures of disciples showing the Anjali Mudra, the gesture of adoration. These sculptures depict the two main disciples of the Buddha who, unlike Sariputta, survived their master and played a leading role in the Sangha after the Parinirvana. Moggallana, the closest friend of Sariputta, is known as the great teacher. He is credited by legendary accounts to have made the first Buddha image. Kassapa is the the disciple shown with a dark skin. He is the master of spirtitual powers and led the first general council soon after the demise of the Buddha in order to save his teachings and monastic rules. The other standing statues at the sides of the small cave depict the Buddha in Abhaya Mudra, the gesture of fearlessness and reassurance. In contrast to the disciple statues, all Buddha statues in the cave of the Thambalagollewa Temple have curled hair and, sprouting from it, the flame called Siraspata, indicating supreme enlightenment by burning the desires and emotion to free the mind from delusions. The ceiling of the cave shows the Kandyan flower-carpet design. The arch above the entrance door is a typical Makara Torana, known from ancient India as well an found at almost every late medieval and early modern temple in Sri Lanka.

A second cave, usually hidden behind a curtain, is deucated to a Hindu deity also venerated by Sinhalese Buddhists. The large modern chart beside the entrance to this small Devalaya shows Vishnu, who is identified with the Sinhalese god Upulvan, who is a major guardian deity protecting the island as well as the Buddhist faith. The third cave has a large reclining Buddha.

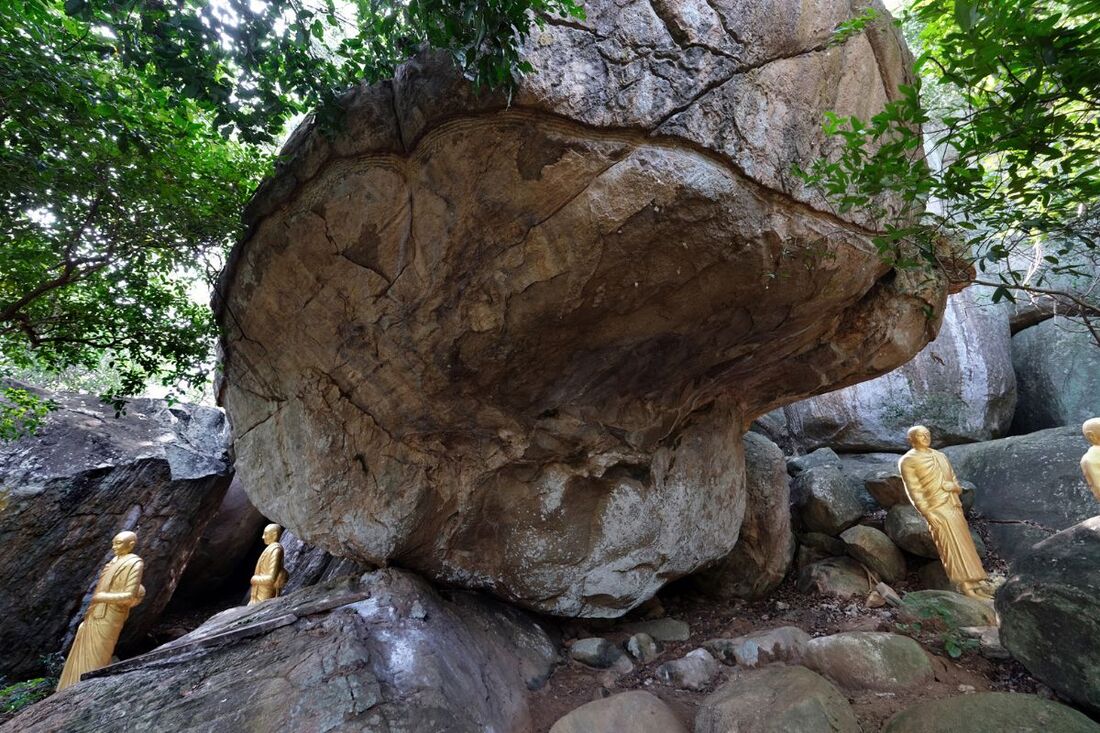

Rocky hill of Thambalagollewa

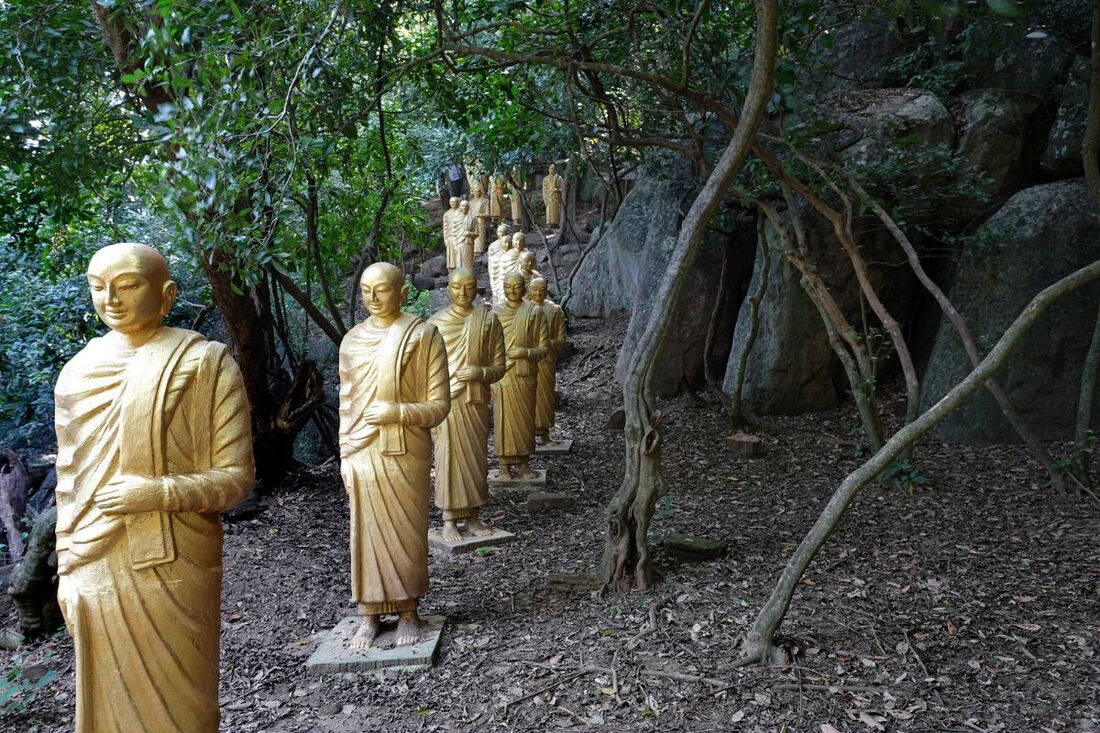

The rock of the Thambalagollewa Kuda Dambula Vihara can be climbed. Rock shelters once used as abodes of forest monks and an excellent vantage point with views to the Wewalketiya tank and the hills of Handagala to the north are well worth the short climb. For the most part, the trail runs along a newly erected long row of monk statues. There have been constructed several lines of statues like this in Sri Lanka in the last decade, but this one is exceptional insofar as the statues are placed in an otherwise untouched jungle. In this idyllic setting, the shimmmering statues come as an eyecatching surprise.

Location of Thambalagollewa

The abovementioned Handagala Kanda is 5 km (3 miles) distance, as the crow flies, but driving distance is 9 km (almost 6 miles). Both lonesome monateries in the northern part of Anuradhapura District border the bushlands of the historical Vanni region, which mainly belongs to Vavuniya District today. Be aware, that not only in ancient times the Vannis were famous for elephants. Wild elephants still frequent this area. Encounters with wild elephants sholud be avoided, they always entail a risk of danger to human life.

As said, Thambalagollewa is situated in a very remote rural and partly wild area. The nearest town is Kahatagasdigiliya at the Anuradhapura-Trincomalee Road (A12), it's in 17km (10.5 miles) driving distance to the south. Horowupotana, also crossed be the said A12 road to Trinco, is in 23 km (14 miles) distance, whereas Medawachchiya at the Mihintale-Vavuniya road (A 9) is 20 km (12.5 miles) to the west of Thambalagollewa. Road distances from Anuradhapura and Mihintale to the Little Dambulla of Thambalagollewa are 42 km (26 miles) resp. 32 km (20 miles).

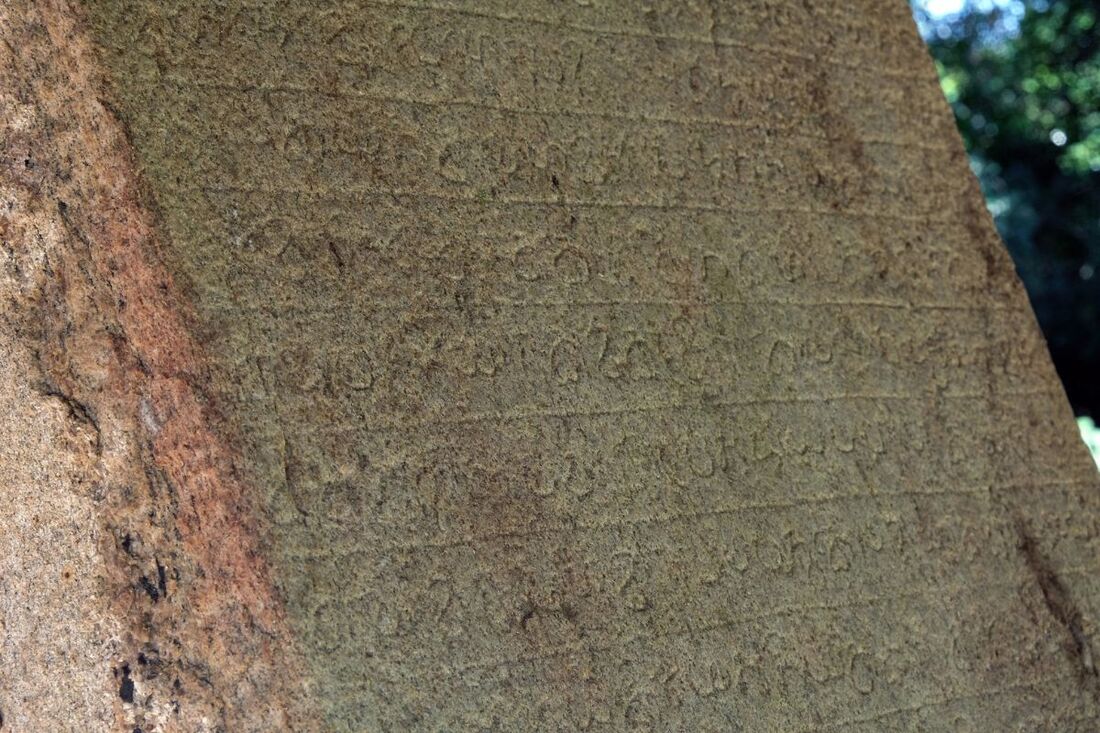

Wewelketiya Slab Inscription

A few hundred meter to the west of the Kuda Dambulu temple, just at the opposite side of the rocky hill, is a significant document of the islan history, a large pillar inscription from the late Anuradhapura period. It's named after the location, Wewelketiya, which is sometimes transcribed Wewalketiya or Vevalketiya. The wide shape of the so-called Wewelketiya Pillar Inscription resembles more a tablet, so slab inscription would be a more appropriate term for it. The Wewelketiya Slab Inscription measures almost 2 m (6 feet, 6 inches) in height and 50 cm (1 foot 8 inches) in width. The text is arranged in 45, the letters are engraved between horizontal lines.

The Wewelketiya Slab Inscription, just like the famous large Jetavanarama inscriptions and the Mihintale Tablets, is ascribed to King Mahinda IV (956-972) and dated to his second regnal year. The eoyal name given in the inscription is Sirisangbo Abha. It's often the case that the names of a Sri Lankan king can differ in inscriptions and chronicles and that personal names continued to be used besides a regnal name.

The language of the inscription is an ancient form of Sinhalese. The historical information value of the Wewalketiya Slab Inscription is that it deals with criminal law, whereas the other 2 large slab inscriptions of the same king discuss donations for the maintenance of monasteries or rules of monastic self-administration. However, contemporary large inscriptions mainly concerned with crime and punishment are known from several regions of the island. In such penal code inscriptions mentioning examplary crimes and punishments, the king grants the power to implement the laws to local rulers in charge of administrational units that consist of ten villages. Such units, also of relevance in Indian history, are known as Dasagamas in Sri Lanka.

The language of the inscription is an ancient form of Sinhalese. The historical information value of the Wewalketiya Slab Inscription is that it deals with criminal law, whereas the other 2 large slab inscriptions of the same king discuss donations for the maintenance of monasteries or rules of monastic self-administration. However, contemporary large inscriptions mainly concerned with crime and punishment are known from several regions of the island. In such penal code inscriptions mentioning examplary crimes and punishments, the king grants the power to implement the laws to local rulers in charge of administrational units that consist of ten villages. Such units, also of relevance in Indian history, are known as Dasagamas in Sri Lanka.

Some other aspects of such royal edicts from the late Anuradhapura period might be worth considering here:

- The term for "granting" in the context of conferring the right to carry out justice is a derivation from "pamanu", the same term that is otherwise used in inscriptions for granting entitlements to income from land. One could say, in ancient Sri Lanka judicial self-rule on a regional level was handled as a kind of privilege to be affirmed in decrees that literally were set in stone by the king.

- Regarding the content, the crimes quoted in the Wewelketiya Slab Inscription comprise not only felonies such as murder and mugging, but also killing of cattle and gaots. However, it would go too far to interpret this as an early example of animal right protection inforced by the laws, though this was known in South Asia indeed. Concerning our specific case from the late Anurahapura period, however, parallels in the Jewish Bible indicate that the reason for punishing the killing of animals is usually that these specific animals served as means to earn the livelihood of human beings.

- The penalty for murder and mugging and killing of cattle or goats that are provided in the Wewelketiya Slab inscription is capital punishment. Pertaining to the killing of animals, this is rigid anyway. It's all the more remarkable as critique of the death penalty was well known in Buddhism and as capital punishment had already veen abolished by previous kings in Sri Lanka (and contemporary India), particularly in the mid Anuradhapura period (first half of the first millennium AD).

- The term for "granting" in the context of conferring the right to carry out justice is a derivation from "pamanu", the same term that is otherwise used in inscriptions for granting entitlements to income from land. One could say, in ancient Sri Lanka judicial self-rule on a regional level was handled as a kind of privilege to be affirmed in decrees that literally were set in stone by the king.

- Regarding the content, the crimes quoted in the Wewelketiya Slab Inscription comprise not only felonies such as murder and mugging, but also killing of cattle and gaots. However, it would go too far to interpret this as an early example of animal right protection inforced by the laws, though this was known in South Asia indeed. Concerning our specific case from the late Anurahapura period, however, parallels in the Jewish Bible indicate that the reason for punishing the killing of animals is usually that these specific animals served as means to earn the livelihood of human beings.

- The penalty for murder and mugging and killing of cattle or goats that are provided in the Wewelketiya Slab inscription is capital punishment. Pertaining to the killing of animals, this is rigid anyway. It's all the more remarkable as critique of the death penalty was well known in Buddhism and as capital punishment had already veen abolished by previous kings in Sri Lanka (and contemporary India), particularly in the mid Anuradhapura period (first half of the first millennium AD).