Dambadeniya was Sri Lanka’s capital in the 13th century. Many tourists cross Dambadeniya, when travelling from Negombo to Anuradhapura or Dambulla via Kurunegala. Most travellers don’t know that Dambadeniya is of historical significance and that there are two rewarding attractions in only a few hundred metres distance from the B308 mainroad crossing the otherwise inconspicuous village. Foundations of the royal palace can still be seen on a quite impressive monadnock. The rock is accessible via a stairway, which is partly from the Middle Ages. The vistas are rewarding. The main temple of the Dambadeniya kingdom, which once served as the Tooth Temple, is located in the plains 500 m west from the palace rock and 500 m southeast from the mainroad. Though some original pillars and carved stones from the Dambadeniya period are still in situ, what can be seen today is mainly the result of a restoration in the 18th century. Hence, the temple’s architecture and decoration style is typical of the Kandy period. Particularly the murals of the upper storey shrine room are excellent examples of Kandyan paintings.

Besides our overview section for your quick information,

you can also find detailed descriptions, by clicking the light-blue tabs "temple" or "rock"

you can also find detailed descriptions, by clicking the light-blue tabs "temple" or "rock"

-

overview

-

history

-

temple

-

rock

<

>

What to see in Dambadeniya

|

The first of two must-sees in Dambadeniya is the Buddhist temple known as Vijayasundarama (Weejayasundaramaya). The pivotal structure of this monastic compound is the image house, which is commonly considered to be a former Tooth Temple of the mid 13th century (or at least a Kandyan period building at the exact place of that Dambadeniya period Tooth Temple). However, it's questionable if the Tooth Temple was within the major temple compound of Dambadeniya at all. Usually, a Tooth Temple is situated closer to the royal palace than to the largest monastery of a capital.

|

|

Some stone elements of the Dambadeniya temple date back to the Dambadeniya period in the late Middle Ages indeed. However, the wooden superstructure is mainly from the Kandyan period. The type of construction as well as the style of decoration are typical of the Kandyan art. For example, four dangling lotus flowers are the typical ornamentation of Kandyan style column capitals. Remarkably, the column is made of stone. It's older than the wooden chapiter. The wooden roof of the front hall (Mandapa) of the temple building is moderate in size but of noteworthy quality.

|

|

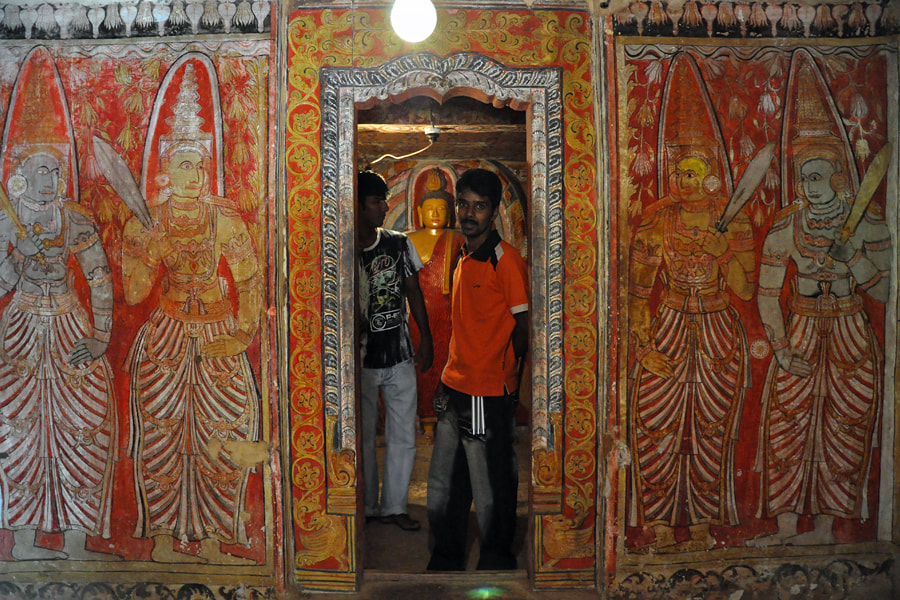

Just like the famous Tooth Temple in Kandy, the main temple building in Dambadeniya has an upper floor. Access can be provided by monks or assistants of the Vijayasundarama. The small chambers of the upper storey are richly decorated with murals in the typical style of Kandy paitings. Doorkeepers, so-called Dvarapalas, flank the passage to the shrine room.

|

|

There is only one statue in the shrine room of the upper storey. Not surprisingly, it depicts a Buddha. A standing position of the main idol, however, is rare in temples of the Kandyan period. What's quite common in Kandyan temples is the large number of stylized lotus blosssoms decorating the ceiling.

|

|

The image house is surrounded by other temple buildings such as a stupa (under a roof) and a Bo-tree (on an ancient terrace) and further image houses, one containing a large modern Buddha in recumbent posture. The postcolonial style of Sri Lanka's Buddha statues is extremely gaudy, not convincing lovers of Buddhist art. But you should be aware, that also in historical times the very most Buddhas sulptured in Sri Lanka were coloured and not showing a stone surface as they do today.

|

|

The second attraction of Dambadeniya is the rock known as Maliga Gala. Maybe, this former royal residence and fortress is even more appealing than the temple, at least to those who like to see historical sites in charming natural settings. Though there is not much left of the former royal residence, because it was made mainly of wood, the archaeological site atop the Dambadeniya Rock is of historical significance for Sri Lanka, undisputably. One of the most interesing features is the original stairway to the summit. The stairway was designed as a military defence system.

|

|

Remnants of the former royal palace are partly restored. Of course, climbing to the top of Dambadeniya is not only recommendable for those studying excavations at archaeological sites but also for lovers of nature. Lots of birds can be heard and spotted here. And the vistas to the green surroundings are rewarding the little strains of climbing the historical stairway.

|

Dambadeniya’s history in short

At the time when Polonnaruwa was hit by the invasion of King Magha from Kalinga, one of his Sinhalese adversaries chose Dambadeniya as his new stronghold. He became the most important Sinhala ruler of his time and was able to repel invaders in his area, which was to the southwest of the heartland of the ancient Sinhaelse civilisation, which remained under foreign occupation. He called himself Vijayabahu III and is counted as the first Dambadeniya king. From Dambadeniya, he reigned only a few years (1220-24) but started effectively reorganizing the Buddhist Order during this short period.

His son and successor Parakramabahu II (1224 or 1234 till 1269) became the most important figure of this so-called Dambadeniya period, which saw a renaissance of Sinhala culture, in particular a golden age of historical literature. Parakramabahu transferred the tooth relic to Dambadeniya, as a symbol of legitimacy of his rule. He also was engaged in a reform of the Buddhist Order, the code of conduct set up around the mid of the century is still extant.

His son and successor Parakramabahu II (1224 or 1234 till 1269) became the most important figure of this so-called Dambadeniya period, which saw a renaissance of Sinhala culture, in particular a golden age of historical literature. Parakramabahu transferred the tooth relic to Dambadeniya, as a symbol of legitimacy of his rule. He also was engaged in a reform of the Buddhist Order, the code of conduct set up around the mid of the century is still extant.

Dambadeniya’s history in some more detail

Dambadeniya is situated in Sri Lanka's Northwestern Province, which is known as Wayamba Pattala in Sinhala. In the early Anuradhapura period, this region and that of the neighbouring Western Province together (more precisely: the region between the rivers of Deduru Oya aund Kalu Ganga) were called Mayarata, with Kelaniya as the capital. In the later Anuradhapura period, the name Dakkhinadesa is more common in Pali chronicles. "Dakkhinadesa" means "southern country", the name refers to the location in a southern direction when seen from the ancient capital Anuradhapura. In the later Anuradhapura period, the Dakkhinadesa was often ruled by the crown prince of the Anuradhapura king. In the Polonnaruwa beriod, it became a more separate political uniot, at least prior to Parakrambahu I, who reigned Dakkhinadesa from Panduwasnuwara, before coming to the throne in Polonnaruwa, using Dakkhinadesa as his powerbase.

Dambadeniya's name

The historical Pali name of Dambadeniya is Jambudoni. Actually, this is not a different name, only a different spelling in only a different language. Similarly, the modern Sinhalese word for the port and temple of the ancient Jambukola is Dambakola. The ending “deniya” is a very common in Sinhalese toponyms. The original meaning is “village in paddy fields”. “Jambu” in Pali means Malabar Plum (Syzygium cumini, also known as black plum or also rose apple) The tree is native to the Indian peninsula and the Indian name is the origin of the modern English name “Jambul”. It’s related to the rose apple (Syzygium jambos) of Southeast Asia, the scientific Latin name of which is derived from the Indian “Jambu”. The Jambu tree is somewhat an iconic tree of India. And one of the ancient autochthon names of India (besides “Bharat”) is “Jambudvipa” in Sanskrit or “Jambudipa” in Pali. More specifically, this is a mythological name of the central continent of the earthly part of the universe. In Sri Lanka’s Pali chronicles, however, “Jambudipa” often is used as the geographical name of India.

Vijayabahu III, founder of the Dambadeniya kingdom

Vijayabahu III, the first king in Dambadeniya, had been a chieftain known as Vanniraja, before he ascended the throne in Dambadeniya, thereby establishing a new Sinhalese dynasty. The name “Vanniraja” (“Vanni-king”) indicates that he originally was from the Vanni region, forested or scrubland areas, most of them situated to the north of Anuradhapura.

Most probably, Vijayabahu III had no kinship ties with the previous king, but he managed to take effective control in the west and southwest, a region then known as Mayarata. Due to his reputation as a reliable Buddhist ruler in a time of turmoil in Polonnaruwa and maybe even persecution of the Buddhist faith, Vijayabahu was rewarded by the Buddhist clergy by entrusting him the national Palladium, the Tooth Relic, which had been kept in hiding in Kotmale in the central highlands, to protect it from the foreign invaders ruling in Polonnaruwa. Vijayabahu III built a temple for the Tooth relic in Beligala, halfway between Dambadeniya and the highlands.

Vijayabahu’s ambition was to strengthen Buddhism in his small empire. The king is said to have taken care that sacred Pali texts were translated into Sinhala to become more popular among common people. He is also credited with having restored many temples and having built the "Vijayasundarama" in Dambadeniya. Following the example set by Ashoka and some highly relevant Sinhalese kings, Vijayabahu III held a convent to purify the Order from secularised elements. Like the convent under Parakrambahu I of Polonnaruwa, the monks layed down new rules to strengthen the observation of canonical rules and again introduced the position of a religious leader, a "Sangharaja", to secure monastic discipline. When Vijayabahu III ascended the throne in Dambadeniya in 1232, the two divisions of the Sangha known as village-monks (Gamavasins) and forest-monks (Arannavasins or Vanavasins) had already emerged. The leaders of both factions presided the convocation of Buddhist monks. The aim was to purify the Order by expelling monks who had offended monastic rules. Establishing a kind of supraregional administrational hierarchy, however, in itself is a concept that was absent from the canonical Vijaya rules. The chief monk of the forest-monks was a cleric called Medhankara from Dimbulagala. The new code of conduct drawn up by the congregation is sometimes attributed to as Dambadeni Katikavata. But this name is somewhat misleading, as the well-known Dambadeniya Katikavata dates from the reign of Vijayabahu’s son and successor Parakramabahu II. A purging of the Sangha was again conducted around 1266 under this most renowned Dambadeniya king. Several monks were expelled from the Buddhist Order and a new formal code of conduct was promulgated. It is the latter document that is still extant and known as Dambadeni Katikavata (also transliterated “Dambadeniya-Kathikawatha”. This Dambadeni Katikavata reserves a royal title (“Maharajano”) only for Parakramabhu II. His father’s title is given as “Vat-himi”, the meaning of which is not entirely clear but almost certainly not referring to kingship. Nevertheless, Vijayabahu deserves to be called the founder of the Dambadeniya kingdom.

Most probably, Vijayabahu III had no kinship ties with the previous king, but he managed to take effective control in the west and southwest, a region then known as Mayarata. Due to his reputation as a reliable Buddhist ruler in a time of turmoil in Polonnaruwa and maybe even persecution of the Buddhist faith, Vijayabahu was rewarded by the Buddhist clergy by entrusting him the national Palladium, the Tooth Relic, which had been kept in hiding in Kotmale in the central highlands, to protect it from the foreign invaders ruling in Polonnaruwa. Vijayabahu III built a temple for the Tooth relic in Beligala, halfway between Dambadeniya and the highlands.

Vijayabahu’s ambition was to strengthen Buddhism in his small empire. The king is said to have taken care that sacred Pali texts were translated into Sinhala to become more popular among common people. He is also credited with having restored many temples and having built the "Vijayasundarama" in Dambadeniya. Following the example set by Ashoka and some highly relevant Sinhalese kings, Vijayabahu III held a convent to purify the Order from secularised elements. Like the convent under Parakrambahu I of Polonnaruwa, the monks layed down new rules to strengthen the observation of canonical rules and again introduced the position of a religious leader, a "Sangharaja", to secure monastic discipline. When Vijayabahu III ascended the throne in Dambadeniya in 1232, the two divisions of the Sangha known as village-monks (Gamavasins) and forest-monks (Arannavasins or Vanavasins) had already emerged. The leaders of both factions presided the convocation of Buddhist monks. The aim was to purify the Order by expelling monks who had offended monastic rules. Establishing a kind of supraregional administrational hierarchy, however, in itself is a concept that was absent from the canonical Vijaya rules. The chief monk of the forest-monks was a cleric called Medhankara from Dimbulagala. The new code of conduct drawn up by the congregation is sometimes attributed to as Dambadeni Katikavata. But this name is somewhat misleading, as the well-known Dambadeniya Katikavata dates from the reign of Vijayabahu’s son and successor Parakramabahu II. A purging of the Sangha was again conducted around 1266 under this most renowned Dambadeniya king. Several monks were expelled from the Buddhist Order and a new formal code of conduct was promulgated. It is the latter document that is still extant and known as Dambadeni Katikavata (also transliterated “Dambadeniya-Kathikawatha”. This Dambadeni Katikavata reserves a royal title (“Maharajano”) only for Parakramabhu II. His father’s title is given as “Vat-himi”, the meaning of which is not entirely clear but almost certainly not referring to kingship. Nevertheless, Vijayabahu deserves to be called the founder of the Dambadeniya kingdom.

Dambadeniya’s power struggle with Polonnaruwa

The 13th century saw the decline not only of the Polonnaruwa kingdom but of the entire agricultural heartland of the ancient Sinhalese civilization, namely in the regions of Rajarata (today’s Cultural Triangle) and Rohana (southern and eastern coastal plains). A trigger of this “fall of Polonnaruwa” was the tyrannical rule of Magha in Polonnaruwa and the entire northern half of the island. Magha conquered Polonnaruwa in 1215. He was a foreigner, a chieftain or prince from Kalinga, which is roughly corresponding modern-day Odisha in the eastern part of the Indian Peninsula. The Kalingas, besides the South-Indian Tamil dynasty of the Pandyas, had been playing a role as the two major branches within the Sinhalese royal family of Sri Lanka since the beginnings of the Polonnaruwa kingdom. It might well be, that Magha’s claim to the throne in Sri Lanka had some legitimacy. Though it is disputable whether he was actually an uduroper, in Sri Lanka’s historiography he is - appropriately - considered to have been as a cruel and destructive foreign invader and a Hindu fanatic. The last part of the so-called Chulavamsa, a sequel of the Mahavamsa, was layed down in the Dambadeniya period, it portraits Magha as a heretic, who looted Buddhist sanctuaries, and as an oppressor of the local population, forcing them to convert to his “false religion”. Be aware, Magha was the main opponent of the Parakramabahu II, on whose behalf this part of the Mahavamsa-Chulavamsa was composed by panegyrists. The reason for emphasizing the evil character of Magha is the hostility of the newly established Dambadeniya dynasty against the mighty ruler of Polonnaruwa. However, there can be little doubt that Magha’s rule was reckless against the island’s Buddhist institutions. Nonetheless, one should be cautious not to identify Magha with Tamil invasions too quickly, although the chronicles call him “Damila” and he was actually a prince of the Eastern Gangas, who possibly were descendents of the Western Gangas, who were of South Indian origin indeed. More importantly, the Eastern Gangas were intimately connected to the Tamil dynasty of the Cholas by marriage. Nevertheless, Odisha (Orissa) is not part of the Tamil and Dravidian south of India. The Eastern Gangas of Kalinga were rivals of the Tamil Pandyas, particularly in their strife for control over Sri Lanka. Tellingly, the mercaneries recruited by Kalinga Magha were not Tamils in the narrow sense of the word, but Malayalas (Drawidians from the territory of today’s Kerala state in southwest India).

Magha’s mercanery army was not the only foreign force on the island in the decades of the mid 13th century. Another invasion took place at almost the same time, namely by an naval force under the leadership of Chandrabhanu, who, despite his Indian royal name, was almost certainly of Southeast Asian origin, namely a former king in Tambralingha in today’s southern Thailand. Chandrabhanu and the Dambadeniya king, though soon afterwards enemies due to Chandrabhanu’s attempts to gain the Tooth Relic, attacked Magha at the same time, thereby weakening and soon terminating the predominance of Magha’s rule in Sri Lanka. The result of Magha’s defeat, however, was not a restitution of the ancient powerhouses (Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Rohana), but a division of the northern part of the country between the spheres of influence of the Sinhalese kings reigning further southwest from now on and the very north, which was first under the control of Chandrabhanu and later on under the Aryachakravartins, a Tamil dynasty of Indian origin.

On the other hand, the dynasty reigning in Dambadeniya was not the only Sinhalese family of chieftains fighting wars against Magha and Chandrabhanu. Other - and maybe rivalling - Sinhalese strongholds in the very beginning of the Dambadeniya period (under Vijayabahu III) were Yapahuwa (under a general named Subha) and Gangadoni (near modern-day Minipe at the Mahaweli River, under general Sankha). The Govindamala mountain (later nicknamed “Westminster Abbey”, near Gal Oya) under Rohana’s Prince Bhuvenaikabahu was a Sinhalese stronghold controlling the southeast of the island. However, of those only Dambadeniya still played a major role some decades later on, when Magha was finally expelled by other foreign invaders. Despite all regionalism and international interventions in the 13th century, the Dambadeniya kings were significant enough to issue their own coins, the so-called Dambadeni Kasi.

Another centre of power – aready mentioned above – was heavily influencing the events in Sri Lanka. The Pandya power arose in Madurai in neighbouring southern India during the founding period of the Dambadeniya kingdom in Sri Lanka. The Pandyas had managed to get rid of Chola overlordship in India at the time of Kalinga Magha’s invasion in Sri Lanka and within a few decades became the new hegemonic power in the entire Tamil area and beyond, terminating the Chola rule forever. It is known from their own inscriptions in southern India, not as much from Sri Lanka’s chronicles, that the Pandyas intervened on the island several times in the mid of the 13th century. According to the University of Ceylon History of Ceylon (Vol 1.2) it is most likely, that it was Sundara Pandya’s invasion that caused Magha to leave Polonnaruwa. This campaign of the Pandyas indirectly assisted the Sinhalese monarch, Pasrakramabahu, though presumably the Dambadeniya king was regarded more as a subordinate than an allie by the Pandyas.

Magha’s mercanery army was not the only foreign force on the island in the decades of the mid 13th century. Another invasion took place at almost the same time, namely by an naval force under the leadership of Chandrabhanu, who, despite his Indian royal name, was almost certainly of Southeast Asian origin, namely a former king in Tambralingha in today’s southern Thailand. Chandrabhanu and the Dambadeniya king, though soon afterwards enemies due to Chandrabhanu’s attempts to gain the Tooth Relic, attacked Magha at the same time, thereby weakening and soon terminating the predominance of Magha’s rule in Sri Lanka. The result of Magha’s defeat, however, was not a restitution of the ancient powerhouses (Anuradhapura, Polonnaruwa, Rohana), but a division of the northern part of the country between the spheres of influence of the Sinhalese kings reigning further southwest from now on and the very north, which was first under the control of Chandrabhanu and later on under the Aryachakravartins, a Tamil dynasty of Indian origin.

On the other hand, the dynasty reigning in Dambadeniya was not the only Sinhalese family of chieftains fighting wars against Magha and Chandrabhanu. Other - and maybe rivalling - Sinhalese strongholds in the very beginning of the Dambadeniya period (under Vijayabahu III) were Yapahuwa (under a general named Subha) and Gangadoni (near modern-day Minipe at the Mahaweli River, under general Sankha). The Govindamala mountain (later nicknamed “Westminster Abbey”, near Gal Oya) under Rohana’s Prince Bhuvenaikabahu was a Sinhalese stronghold controlling the southeast of the island. However, of those only Dambadeniya still played a major role some decades later on, when Magha was finally expelled by other foreign invaders. Despite all regionalism and international interventions in the 13th century, the Dambadeniya kings were significant enough to issue their own coins, the so-called Dambadeni Kasi.

Another centre of power – aready mentioned above – was heavily influencing the events in Sri Lanka. The Pandya power arose in Madurai in neighbouring southern India during the founding period of the Dambadeniya kingdom in Sri Lanka. The Pandyas had managed to get rid of Chola overlordship in India at the time of Kalinga Magha’s invasion in Sri Lanka and within a few decades became the new hegemonic power in the entire Tamil area and beyond, terminating the Chola rule forever. It is known from their own inscriptions in southern India, not as much from Sri Lanka’s chronicles, that the Pandyas intervened on the island several times in the mid of the 13th century. According to the University of Ceylon History of Ceylon (Vol 1.2) it is most likely, that it was Sundara Pandya’s invasion that caused Magha to leave Polonnaruwa. This campaign of the Pandyas indirectly assisted the Sinhalese monarch, Pasrakramabahu, though presumably the Dambadeniya king was regarded more as a subordinate than an allie by the Pandyas.

Sirisanghabo Dynasty of Dambadeniya

There could have been an additional kinship tie between the Tamil Pandyans and the strongest Sinhalese ruler at that point in time, Parakramabahu II of Dambadeniya. But this is disputed. The reason for the assumption of a kindredship between the new Sinhalese kings and the Tamil Pandyans is found in contemporary records. The background is as follows: The historiography composed at the court of Parakramabahu II depicts the Dambadeniya rulers as legitimate immediate successors of the kings of Polonnaruwa. The chroniclers’ ambition is obviously to leave the impresssion that a branch line of the old royal family now has established a new rule of Sinhala kings in a newly founded capital, Dambadeniya. In his own famous work of poetry, known as Kavsilumina, Parakramabahu II claims to be of Pandu origin (a hero from the Indian Mahbharata epic), just like the Pandyas. Actually, the Pandyas are said to have been named after Pandu. There is also epigraphical evidence for this claim of Parakramabahu II: His inscription at Devundara (Dondra, southern cape of Sri Lanka) states that he was from the lunar race, a designation that applies to the Pandyas of South India, too. The Pandyan lineage had played an important role in the royal family of the Polonnaruwa kingdom anyway. The Pandus, as they were called, had been the rivals of the Kalinga branch at the court in Polonnaruwa already long before the interference of Kalinga Magha. This is why it may come to a surprise – and raise some suspicion - that there is a second and quite contrary claim of royal origin from Polonnuruwa stressed for the legitimisation of the Dambadeniya dynasty. Instead of referring to the Pandus, several works composed in the Dambadeniya period claim Kalinga ancestry for Parakramabahu II. Both contradictory claims, however, serve the same purpose: indicating a kinship tie to the Polonnaruwa kings, though actually the Dambadeniya kings had in fact not been closely related to the former royal family.

This lack of a royal bloodline is actually the main reason why the Dambadeniya kings introduced a new name for their dynasty: Sirisanghabo. Many Sinhalese today think this name was meant to be a reference to the most popular king of Sri Lanka’s history, namely King Sirisanghabo, who reigned in the 3rd century. This association might be deliberately intended indeed. The story of King Sirisanghabo and his self-sacrifice was largely expanded in a chronicle composed in the Dambadeniya period. Many details told about the life of King Sirisanghabo are actually from this chronicle, which is titled Hatthavanagalla-Viharavamsa, and not yet reported in the Mahavamsa. The reference to King Sirisanghabo I, who lived one millennium earlier than the Dambadeniya kings, is also emphasized by the fact that King Vijayabahu III chose Atthanagala (Hatthanagala), then believed to be the site of Sirisanghabo’s seld-sacrifice, as his own burial place, where a stupa carries his ashes. But the chronicles (Chulavamsa chapter 71) trace the lineage of the Dambadeniya kings back to an even earlier period. “Sirisanghabo” is not only a personal name of a famous ancient king, it’s also a family name. The respective clan is said to have been named after the Siri-Sangha-Bo (Holy Buddhist-community Tree) of Anuradhapura, which was brought to Sri Lanka on order of Emperor Ashoka, accompanied by members of a noble family from Ashoka’s court, a clan or family then named after the tree: Sirisanghabo. However, a dynasty named Sirisanghabho has ascended the throne in Sri Lanka not before the founding of the Dambadeniya kingdom.

A symbol of continuity, connecting the Dambadeniya rulers to the previous Polonnaruwa kings, is not only the alleged Pandu or Kalinga kinship. The first act of Parakramabahu II as successor of Vijayabahu III was to transfer the Tooth Relic from Beligala to Dambadeniya, for safekeeping near his residence. The most important emblem of royalty was possession of the Tooth Relic. Ever since the Dambadeniya period, Sri Lanka's chroniclers always recognized that ruler or nobleman or prince as king of the entire island who was in possession - and played effectively the role of the armed custodian - of this national palladium of the Sinhalese.

In conclusion, the following should come close to the truth: The Dambadeniya kings were regionally confined rulers. They were not much more powerful or legitimate than other Sinhalese noble families in other regions in those early days after the fall of Polonnaruwa. The power base of the Dambadeniya kings might have been slightly larger than that of other Sinhalese princes, but the Dambadeniy kings themselves were not strong enough to be the main adversaries of the invaders. They were not capable to effectively fight the foreign rulers then controlling the Polonnaruwa area. But for this purpose, control over Polonnaruwa, they were strongly allied with the new hegemonic superpower in the south of the subcontinent, the Tamil Pandyas, who took control over the diverse regional powers on the island Sri Lanka during and after the decline of the Cholas in mainland India.

This lack of a royal bloodline is actually the main reason why the Dambadeniya kings introduced a new name for their dynasty: Sirisanghabo. Many Sinhalese today think this name was meant to be a reference to the most popular king of Sri Lanka’s history, namely King Sirisanghabo, who reigned in the 3rd century. This association might be deliberately intended indeed. The story of King Sirisanghabo and his self-sacrifice was largely expanded in a chronicle composed in the Dambadeniya period. Many details told about the life of King Sirisanghabo are actually from this chronicle, which is titled Hatthavanagalla-Viharavamsa, and not yet reported in the Mahavamsa. The reference to King Sirisanghabo I, who lived one millennium earlier than the Dambadeniya kings, is also emphasized by the fact that King Vijayabahu III chose Atthanagala (Hatthanagala), then believed to be the site of Sirisanghabo’s seld-sacrifice, as his own burial place, where a stupa carries his ashes. But the chronicles (Chulavamsa chapter 71) trace the lineage of the Dambadeniya kings back to an even earlier period. “Sirisanghabo” is not only a personal name of a famous ancient king, it’s also a family name. The respective clan is said to have been named after the Siri-Sangha-Bo (Holy Buddhist-community Tree) of Anuradhapura, which was brought to Sri Lanka on order of Emperor Ashoka, accompanied by members of a noble family from Ashoka’s court, a clan or family then named after the tree: Sirisanghabo. However, a dynasty named Sirisanghabho has ascended the throne in Sri Lanka not before the founding of the Dambadeniya kingdom.

A symbol of continuity, connecting the Dambadeniya rulers to the previous Polonnaruwa kings, is not only the alleged Pandu or Kalinga kinship. The first act of Parakramabahu II as successor of Vijayabahu III was to transfer the Tooth Relic from Beligala to Dambadeniya, for safekeeping near his residence. The most important emblem of royalty was possession of the Tooth Relic. Ever since the Dambadeniya period, Sri Lanka's chroniclers always recognized that ruler or nobleman or prince as king of the entire island who was in possession - and played effectively the role of the armed custodian - of this national palladium of the Sinhalese.

In conclusion, the following should come close to the truth: The Dambadeniya kings were regionally confined rulers. They were not much more powerful or legitimate than other Sinhalese noble families in other regions in those early days after the fall of Polonnaruwa. The power base of the Dambadeniya kings might have been slightly larger than that of other Sinhalese princes, but the Dambadeniy kings themselves were not strong enough to be the main adversaries of the invaders. They were not capable to effectively fight the foreign rulers then controlling the Polonnaruwa area. But for this purpose, control over Polonnaruwa, they were strongly allied with the new hegemonic superpower in the south of the subcontinent, the Tamil Pandyas, who took control over the diverse regional powers on the island Sri Lanka during and after the decline of the Cholas in mainland India.

Indian allies against Kalinga Magha’s rule in Polonnaruwa

From their inscriptions we know that these Pandyan kings from Madurai in southern Tamil Nadu carried out several interventions on the island. The first one was against Kalanga Magha, the most powerful ruler in Sri Lanka, who was of East Indian origin. Soon afterwards, the Pandyas also defeated Chandrabhanu, the invader from today's Malay Peninsula. The Tamil Pandyas considered both the Tamil principality they newly established in the very north of Sri Lanka and the Sinhalese local princes further south as their vassals. The Dambadeniya kings gained importance through good relationships with this new Indian superpower, whereas the Jaffna principality was more rebellous against Pandya overlordship.

By the way, the Tamil Pandyans later on also helped the Sinhalese kings to regain the Tooth Relic. Though many guides in Sri Lanka believe, that the Pandyans had stolen the Tooth Relic in the second half of the 13th century, it’s much more likely that quite the opposite is true. When the Tamils in northern Sri Lanka managed to come into possession of the Sinhalese national palladium, the Pandyas in South India did not tolerate that ambition of overlordship over the island. Hence, they took away the Tooth Relic from the Tamils of northern Sri Lanka. From there, not from Dambadeniya or Yapahuwa, it was brought to Madurai, only for safekeeping. Soon afterwards, the Sacred Tooth was given back to the Sinhalese kings without them having to fight for it. This was meant as a reward for them by the Pandyans, not a forced concession.

As said, the Dambadeniya rulers, in the eyes of the Buddhist chroniclers, were destined to be the island’s supreme kingss by the possession of this most venerated Buddhist relic. This is why the return of the Tooth Relic by the Pandyans is of high symbolic significance to strengthen the reputation of their most loyal allies on the island, the Sirisanghabo dynasty. Not surprisingly, a Dathavamsa ("Tooth Relic Chronicle"), was composed in this period (13th century) aiming to link the history of Sri Lanka to the fate of this national relic.

By the way, the Tamil Pandyans later on also helped the Sinhalese kings to regain the Tooth Relic. Though many guides in Sri Lanka believe, that the Pandyans had stolen the Tooth Relic in the second half of the 13th century, it’s much more likely that quite the opposite is true. When the Tamils in northern Sri Lanka managed to come into possession of the Sinhalese national palladium, the Pandyas in South India did not tolerate that ambition of overlordship over the island. Hence, they took away the Tooth Relic from the Tamils of northern Sri Lanka. From there, not from Dambadeniya or Yapahuwa, it was brought to Madurai, only for safekeeping. Soon afterwards, the Sacred Tooth was given back to the Sinhalese kings without them having to fight for it. This was meant as a reward for them by the Pandyans, not a forced concession.

As said, the Dambadeniya rulers, in the eyes of the Buddhist chroniclers, were destined to be the island’s supreme kingss by the possession of this most venerated Buddhist relic. This is why the return of the Tooth Relic by the Pandyans is of high symbolic significance to strengthen the reputation of their most loyal allies on the island, the Sirisanghabo dynasty. Not surprisingly, a Dathavamsa ("Tooth Relic Chronicle"), was composed in this period (13th century) aiming to link the history of Sri Lanka to the fate of this national relic.

Literary heritage of the Dambadeniya period

The literary productivity of the Dambadeniya period can also be seen in this context of substantiating legitimacy. The ancient chronicles were updated to include the present Dambadeniya period, in order to demonstrate continuity with the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa kingdoms. It was the famous monk Dhammakitti who wrote a large part of the so-called Chulavansa under the reign Parakramabahu II. It’s first and foremost historiography that was compiled at his court. Apart from the late parts of the Chulavamsa and the abovementioned chronicles (Hatthanagalla-Viharavamsa and Dathavamsa), the literary works composed by monks of the Dambadeniya period include the Pujavaliya, which contains tales related to the Buddha as well as some accounts on the history of the island, the Thupavamsa, which narrates the history of stupa constructions, the Jinacarita, a purely religious poem telling the life of the Buddha, the Rasavahini, collecting 103 stories from India and Sri Lanka, and by the same author the Samantakuta Vannana, a praise of Siri Pada alias Adam’s Peak. Also the Nikayasangraha, a short but nevertheless very important account on the history of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, is sometimes attributed to the Dambadeniya period, though it’s usually considered to be one century younger, this is to say: from the Gampola period.

Compared to earlier periods - that lasted many centuries longer and saw the heydays of the Sinhalese irrigational culture and military strength - the amount of works of literature from the - much shorter and weaker and regionally confined - Dambadeniya kingdom is surprisingly large. Actually, concerning works of historiography, the Dambadeniya period is definitely the culmination of this kind of literary activity in Sri Lanka prior to the invention of the printing press. Only the Kotte period two centuries later can stand comparison with the Dambadeniya period, as another golden age of literary activities in Sri Lanka, but with a different focus: works of poetry.

Compared to earlier periods - that lasted many centuries longer and saw the heydays of the Sinhalese irrigational culture and military strength - the amount of works of literature from the - much shorter and weaker and regionally confined - Dambadeniya kingdom is surprisingly large. Actually, concerning works of historiography, the Dambadeniya period is definitely the culmination of this kind of literary activity in Sri Lanka prior to the invention of the printing press. Only the Kotte period two centuries later can stand comparison with the Dambadeniya period, as another golden age of literary activities in Sri Lanka, but with a different focus: works of poetry.

Parakramabahu II, most significant king of Dambadeniya

However, already King Parakramabahu II himself is held in high esteem as a poet. The famous Dambadeniya king is even considered one of the classic authors of Sinhala literature. He is credited with having translated the most important textbook of Theravada Buddhism, Buddhaghosas Visuddhimagga, into Sinhala. He is also said to be the author of Kavsilumina, an epic poem in Sinhala that makes use of the story of Kusa-Jataka from the Pali canon. His literary activity is only one reason why Parakramabahu II, the longest-reigning and most influential of the kings of Dambadeniya, earned the title “Panditha” (“scholar”). It also became part of his own full royal name, Sanghita Sahitya Sarvagna Panditha Parakrambahu.

Parakramabahu II took care of the restoration of Buddhism on the island even more intensely than his father. For this purpose, he invited monks from the Chola region in southern India- The monks from South India were invited to facilitate a restoration of the ordination line. Parakramabahu II held a big festival for the introduction of a new lineage in monastic consecration ceremonies. It was on this occasion that he issued the Dambadeni Katikavata (Dambadeniya Code) for securing monastic discipline, finalizing or reviving the project of Sangha reform that his father had started. It’s questionable if all rules of the Dambadeni Katikavata are in accordance with the basic rules they intend to reinforce, namely the Vinaya, the canonical rule of the Holy Scruptures. For instance, the Dambadeniya rules restricted access to the order by allowing only those of higher castes to be ordained, which became a tradition in Sri Lanka. But it’s in violation of the Buddha’s intention to abolish the caste system within his Sangha.

Parakramabahu II also established Pirivenas as educational institutions for better education of the monks, based on the classic Mahavihara model of scholarship. The king invited Indian monks for these training purposes, too. He made his own brother a teacher for local monks.

Parakramabahu II took care of the restoration of Buddhism on the island even more intensely than his father. For this purpose, he invited monks from the Chola region in southern India- The monks from South India were invited to facilitate a restoration of the ordination line. Parakramabahu II held a big festival for the introduction of a new lineage in monastic consecration ceremonies. It was on this occasion that he issued the Dambadeni Katikavata (Dambadeniya Code) for securing monastic discipline, finalizing or reviving the project of Sangha reform that his father had started. It’s questionable if all rules of the Dambadeni Katikavata are in accordance with the basic rules they intend to reinforce, namely the Vinaya, the canonical rule of the Holy Scruptures. For instance, the Dambadeniya rules restricted access to the order by allowing only those of higher castes to be ordained, which became a tradition in Sri Lanka. But it’s in violation of the Buddha’s intention to abolish the caste system within his Sangha.

Parakramabahu II also established Pirivenas as educational institutions for better education of the monks, based on the classic Mahavihara model of scholarship. The king invited Indian monks for these training purposes, too. He made his own brother a teacher for local monks.

Vijayabahu IV and Bhuvenaikabahu I

The glory of the Dambadeniya kingdom was not to survive Panditha Parakramabahu for long. Due to to health issues, King Parakramabahu II abdicated in favour of his eldest son, who started to reign as Vijaya Bahu IV around 1268. The new king sought to earn a reputation as the restorer of the historical capitals, Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa. Emphasizing his claims as the rightful dynastic regent in the tradition of the ancient Sinhalese kings, Vijayabahu invited his father for a second coronation ceremony in Polonnaruwa. Furthermore, Vijayabahu IV constructed a wide road between Polonnaruwa and Dambadeniya. For this purpose he hired a large number of people from various parts of the island. This is reported in Chulavamsa 89,13-14.

The ambitious young king, however, died very soon after his father’s demise. Vijayabahu IV was assassinated by his general, who thereby usurped the throne. But Vijayabahu‘s younger brother, Bhuvanaikabahu I, succeeded in escaping the coup and later on defeated and killed the usurper. The new king stayed only a few years at Dambadeniya, before shifting the capital to the newly fortified Yapahuwa.

The ambitious young king, however, died very soon after his father’s demise. Vijayabahu IV was assassinated by his general, who thereby usurped the throne. But Vijayabahu‘s younger brother, Bhuvanaikabahu I, succeeded in escaping the coup and later on defeated and killed the usurper. The new king stayed only a few years at Dambadeniya, before shifting the capital to the newly fortified Yapahuwa.

Vijayasundarama temple in Dambadeniya

Most of the buildings of the main Buddhist temple in Dambadeniya are modern. But the main shrine is from the Kandy period and some parts are even older, particularly the stone foundations and pillars and steles. Not surprisngly, a temple existed at this place already in the Dambadeniya period. The temple was founded already by the first Dambadeniya king, Vijayabahu III. Actually, the name of the temple, "Vijayasundarama” literally translates to "Vijaya's beautiful sanctuary". The temple is really worth visiting when travelling from Negombo to the Cultural Triangle (Dambulla or Anuradhapura) via Kurunegala.

So-called Tooth Temple of Dambadeniya

This main temple in today's village of Dambedeniya is also considered to have been the site of the tooth temple of the capital of the 13th century. Apart from the fact that the building has been significantly redesigned afterwards, it should also be noted that this assumption is debatable. It’s more likely that the tooth temple of the Dambadeniya period was closer to the rock and palace. The reason for this hypothesis is that most of the well-known tooth temples of previous and later periods were not parts of a monastery but attached to the royal residence or located in between the palace and the monastery.

In the case of Anuradhapura, the tooth temple was under the supervision of the Abhayagiri monastery, but it was not located within the precincts of this very large monastery. Rather, it was within the fortified city now called citadel. in the neighbourhoods of court officials and traders. It is known from the travel report of the famous Chinese scholar Faxian (Fa Hsien) that an annual procession was held in which the tooth relic was transferred into the monastery only for the period of the festival. This means, usually it was not kept within the monastery. In Polonnaruwa, the Tooth Temple wasn’t situated in the monastic complex, either. Rather, it was placed halfway between the royal palace (citadel) and the main monastery (Alahena Parivena). Later on, in Kandy, the Tooth Temple almost formed a part of the royal residence and was in a larger distance to the main monastery, which was on the opposite side of a swamp in the river bassin that later on was stowed and now is known as Lake Kandy. Even more importantly, in the case of Yapahuwa, built only half a century later than Dambadeniya, the Tooth Temple was close to the city walls. It’s disputet whether the Tooth Temple was a building at the foot of the rock or part of the imposing complex in a saddle of the rock, halfway to the top. Anyway, it was attached to the secular quarter. The reason for a Tooth Temple’s closer proximity to a royal residence than to a monastic complex is that the king’s ambition was to gain the reputation of being the custodian of this relic, which actually became the national palladium. This development of identifying possession of the Tooth Relic with highest secular power on the island came to a climax in the Dambadeniya period. Thus it seems quite likely that the Tooth Temple of this specific period of Sri Lankan history was attached to the royal residence, too, this means closer to the rock than to the monastic complex of the Vjiayasundarama.

However, the Vijayasundarama could have been a kind of "second tooth temple" for festival days, smilar to the function of the Abhayagiri monastery in Anuradhapura. This is to say: Though not including the permanent shrine of the Sacred Tooth, the main temple of Dambadeniya must have had an intimate ceremonial connection to the cult of the Tooth Relic and may also have harboured the national palladium on special occasions.

Image House (Pilimage) of the Vijayasundarama

Let’s now turn to the current appearance of this central building within the temple compound of the Vijayasundarama. It’s not an imposing edifice but remarkable for several reasons. As with the palaces of the Polonnaruwa period, only the substructure was built of stone. It’s highly likely that the original main shrine from the Dambadeniya period (13th century) also followed this pattern. This building plan then was not changed in later centuries, though most of the structure that can be seen now is from the second half of the Kandy period (18th century). In the religious architecture of Sri Lanka, this type of building - stone foundations with wooden superstructure - was quite common. The groundplan follows the scheme of ordinary Indian temples. A closed shrine room containing the main object of worship has an attached porch or hall (Madapa) for lay visitors joining ceremonies. It is not by accident that the layout resembles that of a Hindu temple. Actually, the Buddhist doctrine and cult and architecture alike incorporated more and more Hindu elements since the Polonnaruwa period, particularly in the late Middle Ages.

Similar double-buildings, consisting of the porch or vestibule and the main tower, are known already from the Anuradhapura period, for example at the Tantric Nalanda Gedige. Hindu temples from the Polonnaruwa period have the same layout. Some other temples of the Polonnaruwa had been Hindu originally, before being transformed into Buddhist image houses, for example at the Ridigama monastery. An increasing Hinduisation of Buddhist buildings and the increased use of wood are characteristics of temple architecture until the late Kandy period.

Wooden superstructures

The wooden roof of this Mandapa-like vestibule is noteworthy. Though it has not the silhouette of a Kandyan-style roof, it is somewhat typical of the Kandyen period, as the beams supporting the roof extend almost radially from the top. This is often seen at wooden constructions in the Kandyan style.

Part of a Hindu building plan is that the roof of the main shrine (Sikhara) is higher than that of the Mandapas. This can also be seen in the case of the main shrine (Pilimage) of Dambadeniya. The building is said to have had even two upper floors originally. But this cannot be taken for granted. Today, there is only one upper storey. It's wooden ceiling is painted not only in the interior of the rooms but also in the loggia in front of the shrine rooms.

Upper storey with Kandyan-style murals

The most interesting part of the main sanctuary of the Vijayasundarama complex is the upper floor. A small and steep staircase leads there. The key for access to the upper storey can sometimes be obtained in the nearby museum building, where the chief monk of Dambadeniya also resides. The superstructure of the Vijayasundarama has two small rooms. The main cult image, a standing Buddha, is placed centrally at the back wall of the second room. The door leading from the antechamber to the second room is flanked by paintings depicting four lifesize guardians, corresponding Davarapala sculptures of Indian temples. They doorkeepers are armed with clubs.

The ceilings are adorned with a quite simple ornamental pattern of floral motifs. This lotus ceiling is otherwise often seen at overhanging rocks in painted cave temples. In Dambadeniya, the ceiling decoration is painted on wood. It’s typical of Kandyan art, that very similar images are painted on very different materials, such as natural rock surfacess, plastered walls or wooden planks.

The side walls of the anterchamber are decorated with typical reddish Kandyan paintings from the 18th or early 19th century. The theme is a common one, scenes from the canonical “birth tales” (Jatakas) are depicted, illustrating the good deeds of the later Buddha Shakyamuni in his previous lives. The individual scenes are arranged like in rows, similar to a comic strip. Whenever children are depicted, it’s quite certain that this is a representation of the most beloved of all Jatakas, namely the story of Prince Vessantara.

The type of illustration is - like the reproduction of biblical scenes in medieval painting - borrowed from the artists own epoch and environment. Elephant processions, being the most magnificent events in a religious year in Kandy or other towns, are a quite popular sujet of Kandy paintings, included in the scenes even if the story line does not really require it. Architectural features such as wooden halls and the dresses in particular correspond to those of Kandy around 1800. The paintings in the temple Dambadeniya are not of the highest quality and they are not as well preserved as in Ridigama or Degaldoruwa and they are probably from a more recent date. However, they allow to study almost the entire spectrum of typical motifs of Kandyan art, gathered in only two small rooms.

In the second room, large vases of abundance can be seen next to the door. In Indian art, such vessels overflowing with foliage are, named Purnagatas , are common symbols of fertility. On the opposite side of the door is an image of a richly decorated nobleman or a king, dressed in the courtly style of the Kandy period. He is carrying a large flower as an offering for the Buddha.

Another typical theme of Kandyan murals can be seen to both sides of the Buddha sculpture. The back room has depictions of lifesize "Buddhist saints" (enlightened beings, Arahants in Pali, Arhats in Sanskrit). They are arranged in rows and columns, most of them show no individual faces, except from one: Moggallana, is usually depicted with dark or even blue skin. Mogallana (Maudgalyayana in Sanskrit) is one of the two foremost disciples, the other one being his friend and counterpart Sariputta (Saruputra), both often depicted next to the Buddha. Moggallana is representing psychic powers, whereas Sariputta represents wisdom and scholarship. Arahants in Kandyan art are easily recognized by two featues, the halo around the head and the lotus flowers in the hand. In the case of the Dambadeniya temple, as an exception from the typiyal arrangement of a seated Buddha flanked by two standing Buddhas, the only Buddha sculpture is standing and flanked by two paintings of Buddhas of almost the same size and also in the posture known as Abhaya Mudra (right hand raised).

Further buildings on the terrace of the Vijayasundarama

Most of the other buildings within the temple compound, a wide courtyard surrounding the central main shrine (which, as said, is sometimes called the “Tooth Temple”), are much later additions. Only some stone fundations and carved stones at the terrace of the Bo-tree are from the Kandyan period or even older. A typical new image house will be opened for a tip to take a look at a garishly colourful reclining Buddha. As in the case of many other recumbent Buddhas, hid favourite disciple Ananda is at his feet.

Remarkably, the stupa on the main terrace of the Vijayasundarama temple is roofed. This Chetiyagara (stupa house) is modern but could well resemble ancient roofed stupas, which were typical of Sinhalese art in the Anuradhapura period.

Apart from image house and stupa, the Bo tree is one of the three objects of veneration that belong to almost every Buddhist temple in Sri Lanka. The Bo tree terrace is situated in the east of the terrace, facing the entrance of the main shrine. As mentioned above, some stone carvings of this terrace are ancient.

Open buildings resembling pavilions are used for teaching purposes, not only for delivering sermons but also as Sunday schools. Futhermore the central terrace of the Vijayasundarama is surrounded by the residential buildings for monks. About half a dozen monks live in this temple, which is a comparatively large number for a village temple, at least in the case of the Syam Nikaya (Siamese Order), to which branch of the Buddhist Sangha this temple belongs, although most Syam Nikaya temples are found in the highlands and North Central Province. Some of the monks residing in Dambadeniya worked as teachers. For organising Sunday school classes, also monks from other monasteries in the surroundings sometimes come for a visit to Dambadeniya.

Museum of the Vijayasundarama

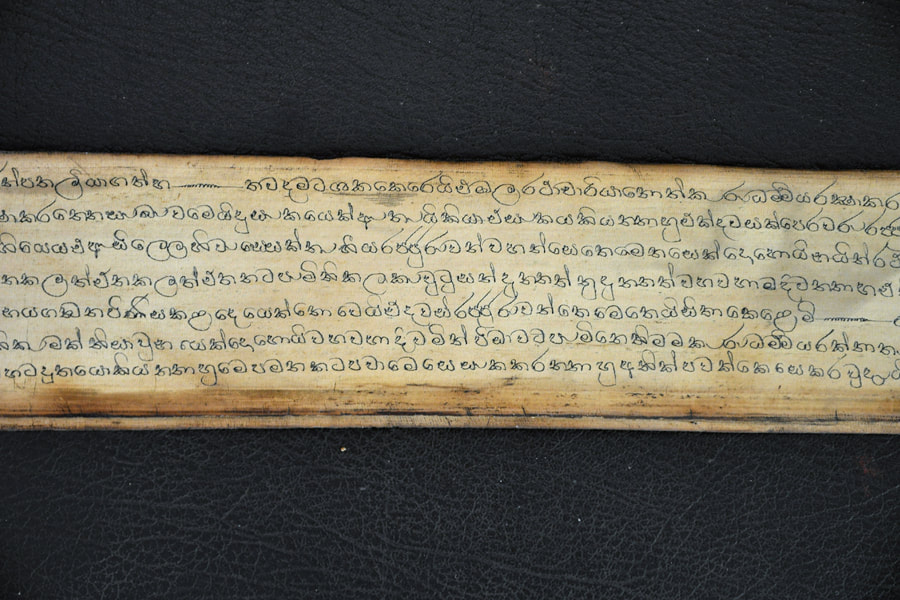

To the northwest of the main courtyard of the temple, some steps further down, is a new building where the chief monk of Dambadeniya resides and welcomes his guests. Also foreigners can have good luck to be welcomed by him personally. Thick stacks of palm-leaf manuscripts hang at the walls of an antechamber. These manuscripts are 500 years old, they contain a part of the Pali canon known as Tiptiaka, more specifically: the 550 Jataka stories, which form a part of the Kuddhaka Nikaya, the so-called “short texts”, that are one of the five sections of the Sutta Pitaka, the “basket of Sutras”. Younger bundles of ola leafs, also containing Jataka tales, are sometimes opened for visitors, allowing them to study the Sinhalese letters (also used for texts written in Pali), which were carved and afterwards blackened, Sinhalese letters are .

An adjoining room serves as a small museum. There is usually no entry fee, but the efforts of the friendly monks taking their time to invite curious foreign guests should be rewarded with a donation. Dambadeniya is not a tourist hub. This is why foreigners are ususlly not treated as a mere business opportunity in the Vijayasundarama. Apart from further palm leaf manuscripts, there are also volumes of Buddhist scriptures in bound books. Some archaeological finds are kept in the cabinets, especially coins from the Dambadeniya period, including a Chinese one, which is punched in the centre. Coins from later periods are collected in a separate cabinet. The small museum also serves as a kind of sacristy, safekeeping ancient ritual objects. The charm of this very small museum is, as I said, the helpfulness of the monks to see various objects of interest.

Maliga Gala - Dambadeniya's Castle Rock

|

Royal residences in Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa had been fortified or were part of a fortified city. But in the times of war in the period of the decline of Polannaruw and afterwards the new royal residences in the new capitals further south were fortified in a completely different manner: The new royal palaces were built on isolated rocks. It is debated if in antiquity already Sigiriya had been a rock palace of this kind rather than a very normal fortified royal city just including a rock that served more as a place of worship than a royal palace. However, the larger part of the royal residence of Sigiriya had steen bill on ground level. The military protection of royal residences in the 13th and early 14th was definitely the elevated location on a steep inselberg or monadnock. This is the case in the subsequent capitals of Yapahuwa and Kurunegala alike. The first example of this kind of royal stronghold in the Middle Ages is Dambadeniya. In the case of Dambadeniya, the fortification system was changed completely, from artificial walls to natural vertical slopes. Maybe, there were no city walls at the Dambadeniya Rock at all, although they again were included in the fortification of Yapahuwa Rock (100 km further north) some decades later on. In the case of Dambadeniya, only few traces of walls can be seen when climbing the rock, but it’s uncertain if they are from the Dambadeniya period or much later additions. The city walls of Dambadeniya might have encompassed a much larger area, including the settlements of subordinates.

|

Dambadeniya's main attraction is the palace rock, not the structure in itself but the natural setting in which it is embedded. The Sinhala name of the monadnock is Maliga Gala, which literally translates to “palace rock”.

Ancient stairway to Dambadeniya Rock

For visitors, ascent is easier manageable than at the rocks of Sigiriya or Yapahuwa, since the granite monatnock of Dambadeniya is not quite as high and, more importantly, the stairway to the top is more comfortable and almost never frequented by other tourists. Access to the stairway is now from the south, where also an office of the Archaeological Department is situated. However, the historical stairway commenced at the western slope. Both flights of stairs now meet at a point that is of some interest and has to be discussed now.

Actually, the stairway to the top of Dambandeiya Rock is an attraction in itself. It’s from the Dambadeniya period and it was part of the defense system. In a sense, the design of the Damabdeniya stairway is a fortification in itself. It was designed to facilitate a defense without additional fortified gateways. Instead, the stairway has a narrow bottleneck, allowing not more than one person to pass at the same point in time. An invading army was not able to cross this narrow point with more than one person at a time. So only one defending person (or only very few fighters) would have been enough to prevent an advancing group or army from entering the royal residence. But there is another element that facilitated the defense without walls and gates. The said bottleneck of the Dambadeniya stairway is placed just below the steepest and tallest rock surface. This is not by accident or only natural. Rather, the intended purpose of this location was to allow defenders to throw stones and logans from the top of the slope onto the invading forces, thereby striking the troops when they had to wait as long their first fighter was impeded to enter the stairs behind the bottleck. This kind of trap was not an invention of the Dambadeniya period. Actually, logans with a device to tilt them were used at places of strategical importance already in the Anuradhapura period, namely surrounding the capital in all four cardinal directions.

Throne hall on Dambadeniya Rock

The second and most important king residing in Dambadeniya, Parakramabahu II, is believed to be the one who established the new royal residence atop this rock. Despite the strange location on the uneven summit of a rock, the royal palace follows the pattern of the earlier royal residences in Polonnaruwa, built under Parakramabahu I and Nissanka Malla. The royal residence included both a palace and a throne hall side by side. Already in Polonnaruwa most of the upper storeys were wooden constructions. In Dambadeniya, much larger parts of the building were made of perishable materials. This is why only little remains of the medieval structures.

The throne hall is often called an assembly or audience hall, as it served both purposes, holding meetings of the state council and official receptions of guests and subordinates. It was the place of tribunals, too. This throne hall of the Dambadeniya kings actually is not extant any more. However, the location is clearly identifiable. It was on a rock surface to the left, when entering the terraces of the summit of Dambadeniya Rock, it’s close to the upper end of the flight of stairs. A small pool – one of three pokunas on the summit – is in a very small natural ravine nearby. The place of the former wooden structure on this slightly elevated rock surface is easily recognisable, as there are lots of postholes cut into the rock. Such postholes could carry stone and wooden columns alike. In the case of Dambadeniya, however, now stone columns were found in situ. This means, it’s highly likely that the entire structure of the throne hall was made iof perishable materials. The natural elevation in this case also replaced the stone constructions of terraces that had served as substructure of previous assembly or throne halls like those still extant in Parakramabahu’s citadel and at Nissanka Malla’s royal palace in Polonnaruwa. To put it in other words: The different levels on the wide summit of Dambadeniya Rock allowed to place the assembly hall a slightly higher elevation than the royal palace without any additional construction works. The higher elevation served the purpose of highlighting the administrative function of the king. Every visitor of the king during a ceremony had to advance from a lower level.

Royal Palace on Dambadeniya Rock

In contrast to the separate throne hall, which must have been a wooden construction, the royal palace, situated further north, was built partly of brick. This is now the only building that can be seen atop Dambadeniya rock. The foundations and some brick layers of the royal palace have been restored in recent years by the archaeological department. The royal palace consisted of two parts, a hall on a stone foundation and, in front of it, a courtyard. This resembles the layout of the palace of Parakramabahu I in Panduvasnuwara (35 km further north), which was constructed one century earlier on. However, the structure of the Dambadeniya period is much smaller in size.

The courtyard is edged by a wall made of bricks. Two different types of bricks were used. Normal bricks are used for the most layers. However, some layers consist of tiles that are much thinner and wider. These are tiles of a type otherwise used for rooftops and they serve a similar purpose, they remove the water of rainfall. First of all, the additional thin layers protect the other bricks from erosion. Furthermore, there is a drainage system, holes in the brick wall allowing a runoff of water from the courtyard. Rainfall occurs in much larger quantities in the Dambadeniya area than in the former Sinhalese heartlands around Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa. This is why the construction method had to be adapted. This is also one reason why wooden constructions with tiled roofes – more easily restorable and better sealed – were preferred over stone constructions.

The preference of wood as building material can also be seen from the main hall in the back of the courtyard. A large amount of postholes, that are set surprisingly narrow to one another, once bore wooden pillars. In this case, the pillars were not in the interior of a wooden construction carrying a roof as in the case of the throne hall, but they carried an upper storey that was actually the main room (or more than one room) of the royal palace. Living rooms or bedrooms in upper storeys are a well-known feature of earlier royal palaces, particularly in Polonnaruwa.

Pokunas of Dambadeniya

There were three pools on the Dambadeniya rock. Fed by rain water, they can still be recognised as such Pokunas. It's likely that they served different purposes, not only as cisterns providing drinking water for the inhabitants of the royal residence. The larger one could well have served as a bath, as a pokuna in the classical sense. At least one pool seems to be purely natural, whereas at least the largest one is partly stowed, having a small brick dam to increase the capacity. One very narrow pool, largely natural, is a small chasm very close to the platfrom of the former throne hall (see above).

From the chronicles, it is known that King Parakramabahu II constructed six pools in Dambadeniya. However, this does not seem to refer mto the small pokunas within the royal residence but larger pools in the flat surroundings of the pool that served irrigation purposes for paddy cultivation, just in the ancient Sinhalese tradition of royal care for the fertility of the land and the wellbeing of the people.

Behind the small natural rock pool, which can be seen halfway to the right when advancing the royal palace from the throne hall is the highest peak of the rock. Here are many more square postholes cut in the surface of the rock, indicating that apart from the main palace many more rooms existed. Like in the case of many other wooden palaces in tropical Asia, the entire palace complex must have consisted several small open pavilions and huts scattered all over the compound.

View from Maliga Gala to Waduwa Ketu Gala

It’s worth climbing to the very top, as it has a magnificent view to the west, where the neighbouring rock can be seen. It’s known as Waduwa Ketu Gala and known from folk tales.

So the story goes: The craftsman who constructed the chamber for keeping the Tooth Relic was imprisoned on that rock near Dambadeniya in order to prevent him from falling into the hands of the foreign invaders that ravaged the island at that point in time. The way to the top was protected by guardians and noone was allowed to climb to the top. The wife of the imprisoned craftsman brought him meals that were drawn to the top with a rope. But the wife was clever to smuggle the craftman’s toolkit with beater and chisel. He made use of it by carving steps at the opposite side of the rock which was considered to be too steep for anyone to climb up or down there. It took him many month to carve the steps one by one, but finally he escaped and never was captured again. The stunningly steep carved stairway can still be seen at the Waduwa Ketu Gala indeed. It’s an etiological legend explaining the existence of such a long and steep stone ladder to the sky.

In conclusion: worth a break for those interested in off-the-beaten path attractions

The summit of the Dambadeniya Rock is not a extremely spectacular tourist attraction, but it’s not only a historical place of some interest for heritage travellers, it’s actually a quite charming site. The overgrown former palace complex is now forested and therefore pleasantly shady. Some clearings offer vistas to various directions. The surroundings are rich in palm groves here and paddy fields there. On the top of the rock, you rarely hear voices of other human beings but lots of sounds of crickets and birds, leaving the impression of being amidst a forgotten city in the jungle, though not being far away from the village at a main road taken by many tourists to proceed from Negombo to Sigiriya. Most of them don’t take a break to visit this lovely place, and even tour guides rarely recommend it, though it’s really worth seeing.