The Ritigala Archaeological Site comes close to what can be called picture-book ruins in the jungles, though you should neither expect large structures overgrown by roots of trees as in Cambodia. Ritigala differs from most other archaological sites from the Anuradhapura period. Neither Buddha statues nor stupas nor Bo-tree terraces can be seen here. Instead of this, Ritigala is the best example representing an alternative style of classical Sinhalese monastic architecture, which is called Padhanagara Pirivena. Padhanagaras are double platforms connected by a bridge. Probably, they served as meditation terraces. Such Padhanagaras and their interconnecting paved meditation pathes plus a special structure for Ayurvedic treatments and compartively large ponds with stepped ghats are typical features of monasteries of a somewhat enigmatic reform fraternity called Pansukilikas. Pansukulika means “rag-robes” and refers to a vow taken by these specific monks to wear only garments made from rags found at cremation sites. Monasteries of this Pansukulika or Padhanagara type are also known from Western Anuradhapura, Arankale, Manakanda and Kirilagala, Ritigala being the largest and best specimen. Remarkably, the monasteries of this austere monks living in forests are quite elobarate stone structures, built of huge slabs that are carefully ciselled to fit to each other. Apart from the architectural quality of the buildings, no other works of art are seen in Padhanagara Pirivenas of the Pamsukulika brotherhood. But there is one remarkable exception from this rule: Ornate carvings are seen only at urinal stones of the ancient monasteries’ toilets.

The ruined complex of Ritigale is situated at the eastern base and slope of the highest mountain in the Northwestern Province. The isolated forested hills of Ritigala rise out of the plains and can be seen from far distance, for example from Sigiriya Rock or from Lake Kalawewa. The Ritigala Kanda, known for its quite unique vegetation, must not be climbed by visitors without special permission, as this unique biotop is a strict nature reserve. However, the archaeological site at the westen slope, close to the foot of the hill, is accessible for all travellers.

Ritigala, surrounded by legends and folk tales, is situated right in the centre of the Cultural Triangle, the heartland of the ancient Sinhalese civilization then known as Rajarata. Though not overcrowded, Ritigala is not an off-the-beaten-path location any more, since it is mentioned in many pocket guides and it’s not far away from major tourist destinations. Due to the cluster of hotels and guesthouses in the Habarana and Dambulla and Minneriya area, Ritigala can be reached easily on half-day excursions from almost every hotel in the central region of the Cultural Triangle around Sigiriya. Those tourists who travel from Anuradhapura to Polonnaruwa can include a retour to Ritigala conveniently, too. The distance from First House Mihintale is 51 km via Galenbindunuwewa.

The ruined complex of Ritigale is situated at the eastern base and slope of the highest mountain in the Northwestern Province. The isolated forested hills of Ritigala rise out of the plains and can be seen from far distance, for example from Sigiriya Rock or from Lake Kalawewa. The Ritigala Kanda, known for its quite unique vegetation, must not be climbed by visitors without special permission, as this unique biotop is a strict nature reserve. However, the archaeological site at the westen slope, close to the foot of the hill, is accessible for all travellers.

Ritigala, surrounded by legends and folk tales, is situated right in the centre of the Cultural Triangle, the heartland of the ancient Sinhalese civilization then known as Rajarata. Though not overcrowded, Ritigala is not an off-the-beaten-path location any more, since it is mentioned in many pocket guides and it’s not far away from major tourist destinations. Due to the cluster of hotels and guesthouses in the Habarana and Dambulla and Minneriya area, Ritigala can be reached easily on half-day excursions from almost every hotel in the central region of the Cultural Triangle around Sigiriya. Those tourists who travel from Anuradhapura to Polonnaruwa can include a retour to Ritigala conveniently, too. The distance from First House Mihintale is 51 km via Galenbindunuwewa.

Location of Ritigala - in the centre of the Cultural Triangle

|

The Archeological Site of Ritigala is situated at the eastern slopes of the Ritigala mountain range, the car park and entrance of the excavation site is 20 km to the northwest of Habarana by road. It can be reached from a turn-off at the Habarana-Anuradhapura Road (A11) at a distance of 12 km from Habarana. An 8.5 km along a graveled road leads to the car park of Ritigala at the foot of the mountain range. The distance from Anuradhapura New Town is 55 km, from Polonnaruwa Archeological Site 63 km, from Kandy 113 km, and from Trincomalee 105 km.

|

It’s not recommendable to walk the 8.5 km from the bus station at Galapitagala at the A11 mainroad to the Archaeological Site, since the plains surrounding Ritigala are elephant wildlife area. Along the graveled road you will see numerous small tree houses, they serve as safe resting places of farmers but also as refuges when elephants approach to their paddy fields. Locals have been attacked by wild elephants in this area and fatal incidents occured.

Below, you find an overview article, providing an intro and short descriptions of the ancient buildings of Ritigala.

The Attractions tab is about the same places of interest, but offering detailed explanations.

The Nature tab contains information about the Strict Natural Reserve of Ritigala.

Ramayana tales about Hanuman and Sanjeewani drop surrounding Ritigala are part of the Legends tab.

The History tab, in its second part, has detailed information on the Pamsukulika branch of Buddhism .

The Attractions tab is about the same places of interest, but offering detailed explanations.

The Nature tab contains information about the Strict Natural Reserve of Ritigala.

Ramayana tales about Hanuman and Sanjeewani drop surrounding Ritigala are part of the Legends tab.

The History tab, in its second part, has detailed information on the Pamsukulika branch of Buddhism .

-

Overview

-

Nature

-

Legends

-

History

-

Attractions

<

>

Sri Lanka's Cultural tourist destination Ritigala - an overview

Ritigala, situated half-way between Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa and in 35 km km distance from Sigiriya by road, is the highest elevation of the northern half of Sri Lanka. It's somewhat the Sacred Mountain of the Cultural Triangle, rising just in it's very centre.

Ritigala Mountain shrouded in mystery

The altitude of the highest point of the isolated Ritigala ridge is 766 m above sea level. The uppermost parts are wrapped in clouds most of the time. Due to the humid climate, some plants can grow here that otherwise only inhabit the Sri Lankan highlands. Due to ist extraordinary biodiverity, the higher altitudes of the range are protected as a strict nature reserver. This means, climbing the very top is prohibited, except for biologists with special permissions. Ritigala is famous for ist abundance of medicinal plants in particular.

A famous legend from the Indian Ramayana epic represents the origin of this wealth in herbs. When the hero of the epic, Rama, was almost fatally wounded, there were only very special herbs with very long Sanskrit names from the Himalayas that could cure him. Hanuman flew to the air to northern India, but after arrival at the snow mountains, he had forgotton the complicated designations of those herbs. Thus he cut out an entire massif of the Himalayas to bring it to Sri Lanka. However, on his flight through the air back to Rama, chunks of the massif fell down on the earth, one of them now forming Ritigala. In Hindu mythology, these chunks are called ‚Sanjeewani drops‘, Sanjeewani being the mythical herb that cures all diseases.

Sinhalese legends, partly historical, refer to the wilderness of Ritigala, the ancient Arittha Pabbata, as hideout af various rebellious members of royal families, starting campaigns from this remote jungle to seize the throne in Anuradhapura. However, the namegiving hero, Arittha himself - though being of royal descent, too, namely the nephew of the island’s first Buddhist king, Devamampiya Tissa – was a completely peaceful hermit. He is believed to have settled down in this area after becoming the very first native monk of Sri Lanka and also the first saint (arahant) who had found enlightenment on the island.

A famous legend from the Indian Ramayana epic represents the origin of this wealth in herbs. When the hero of the epic, Rama, was almost fatally wounded, there were only very special herbs with very long Sanskrit names from the Himalayas that could cure him. Hanuman flew to the air to northern India, but after arrival at the snow mountains, he had forgotton the complicated designations of those herbs. Thus he cut out an entire massif of the Himalayas to bring it to Sri Lanka. However, on his flight through the air back to Rama, chunks of the massif fell down on the earth, one of them now forming Ritigala. In Hindu mythology, these chunks are called ‚Sanjeewani drops‘, Sanjeewani being the mythical herb that cures all diseases.

Sinhalese legends, partly historical, refer to the wilderness of Ritigala, the ancient Arittha Pabbata, as hideout af various rebellious members of royal families, starting campaigns from this remote jungle to seize the throne in Anuradhapura. However, the namegiving hero, Arittha himself - though being of royal descent, too, namely the nephew of the island’s first Buddhist king, Devamampiya Tissa – was a completely peaceful hermit. He is believed to have settled down in this area after becoming the very first native monk of Sri Lanka and also the first saint (arahant) who had found enlightenment on the island.

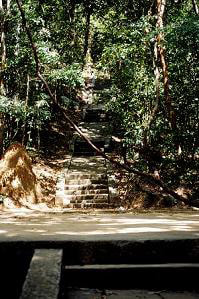

Ritigala Archeologigical Site – largest excavation of a Padhanagara monastery

At the eastern foot of the Ritigala range, there is one of Sri Lanka’s most fascinating archaeological sites. Some caves in this area date back to pre-christian centuries. However, the monastery the remains of which are Ritigala’s main attraction now is from the late Anuradhapura period, the last centuries of the first millennium AD. Ritigala – in ancient times known as Arittha Pabbata – was the largest monastery of an enigmatic Buddhist fraternity called Pansukulikas. They formed the most ascetic faction of Sri Lanka’s Buddhist order. The architecture of their settlements differs sifnificantly from the island’s ordinary monasteries. There were no stupas, no Buddha images and even no Bo-trees inside a monastic complex of Pansukulikas. Instead, Padhanagara meditation platforms are the main edifices, besides artificial ponds and Ayurvedic hospitals and plastered meditation pathes. Climbing the ancient stairways can be a little bit strenuous but will be rewarding. Though the Archaeological Site is said to be safe, be aware that the immediate surroundings are wild elephants‘ roaming area.

1. Bathing pond

|

Close to the ticket office at the very foot of the hill are the partly restored Ghats of the Banda Pokuna. ‚Pokuna‘ is an artificial ponds für bathing, Ghats are the wide steps flanking the pool. In comparison to monastic bathes found in other ancient monasteries of Sri Lanka, the Banda Pokuna was extraordinarily large. The reason for the size may have been that it was not used by monks exclusively but also was a holy bath for pilgrims. Due to ist reputation as a place of healing power and as a dwelling of austere holy men, Ritigala was a quite popular pilgrimage destination in ancient times.

|

2. Reception Hall

|

When climbing the ancient path through the large monastic complex half way, the visitor will arrive at a group of quite plain platforms. They are assumed to have carried a kind of wooden reception hall marking the entrance to the sacred area of the monks. Presumably, visitors were allowed to visit monks behind the reception hall but were not allowed to enter the core complex without invitation or permission or guiding.

|

3. Ayurvedic Hospital

|

One of the most striking structures in the sea of debris of Ritigala ist the so-called hospital. Actually, the function of the building that was surrounding a rectangular shallow pond on all four sides is not entirely clear. Most likely, it was not a refectory but a place for therapeutical treatments indeed, but more a spa than a hospital. Grindstones are still in situ. They were used to prepare the herbs for medicinal bathes. Hot water facilities were included, too. Buildings such as this one are found in all Pansukulika monasteries. They are called Janthagaras, ‚jantha‘ referring to the warmed water, ‚gara‘ simply meaninf ‚house‘.

|

4. Meditation Path

|

Particular behind the level of the reception hall and the nearby Janthagara, the path crossing the upper monastic comped is extraordinarily elaborate. Stone slabs of enourmous size are hewn to fit together precisely. Like Janthagaras, such plastered pathes are typical of Pansukulika monasteries. They served not only as lines of communication but also as meditation pathes, as walking can be one method of Buddhist practice focusing the mind.

|

5. Library

|

One of the most picturesque parts of the Ritigala Archaeological Zone can be reached by leaving the paved meditation path and taking a jungle path to the left. After a few hundred meters it reaches the remains of a building atop a boulder. It is presumed to have served as a kind of sacistry, safekeeping scriptures and other precious ritual objects. The most impressive feature of this ensemble is the monolothic bridge crossing a small chasm.

|

6. Meditation-Platforms

|

The most typical feature of a monastery of the Pansukulika fraternity was the double platform called Padhanagara. The more elaborate of the two platforms was reserved for monks meditating in seated position. The rules of the Buddhist Order known as Vinaya and forming part of the Holy Scriptures recommend that the place of mediation should make sure that the monk will remain undisturbed by snakes and beasts. A clean platform helped to fulfil this purpose. The second platform was provided for lay people visiting the monks but keeping respectful distance. They came here to ask for advice but also venerated the monks, presumably by circumambulations of the monks‘ platform. This is why the largest Padhanagara is surrounded by a courtyard. The bridge between the platforms has lateral steps allowing visitors to climb down to this courtyard.

|

7. decorated urinal stones

|

The most striking feature within a Padhanagara courtyard is the urinal stone. Remarkably, this is the only part of the entire monastery that bears artistic reliefs. All other buildings of the Pansukulikas lack any kind of ornamental decoration. The reason is their intention to lead a life without any distracting luxury. Actually, Pansukulikas were showing their contempt to works of art in this special way: urinating on it.

|

Ritigala Kanda - highest mountain in Sri Lanka's dry zone

Ritigala Kanda, seen from Anuradhapura-Polonnaruwa road A11

Ritigala Kanda, seen from Anuradhapura-Polonnaruwa road A11

Ritigala Kanda, an inselberg made of Precambrian sedements, reaches a height of 766 m above sea level and more than 600 m above the suroounding plains. It’s the highest mountain in Sri Lanka’s plains to the north of the central highlands. Thereby, it’s also the highest peak in the Cultural Triangle. Not surprisingly, Ritigala is part of the main watershed of the island. The spring of the Malwattu Oya is situated near Ritigala. Malwattu Oya, known as Kadamba-nadi in the chronicles, was the main river for irrigation of the Anuradhapura Kingdom, the classic Sinhalese civilization.

The entire Ritigala mountain range consists of four peaks covered by dense forest. The forested mountain massif measures about 6 km from north to south and 3 km from east to west. An area of about 1,500 hectare was declared a Strict Nature Reserve, administered by both the Forest Department the Department of Wildlife of Sri Lanka, as threatened species such as leopards and sloth bears also occur in the sanctuary.

Three neighbouring peaks to the east of Ritigala Kanda form Andiyakanda-henne group. The valley in between is called Veval-thenne. It is home to a spring never drying up. Further north are three more peaks, all of which reach more than 700 m. The steep chasm that separates them from the Ritigala Kanda collects plenty of water during the local rainy season in late autumn and early winter of the northern hemisphere. The stream from this chasm is one of the two tributaries of the Banda Pokuna in the monastic area at the western base of the mountain range. Being the coolest and area in the northern plains of the island and rich in water, Ritigala was a place chosen by the British to establish a sanatorium in the late 19th century.

Ritigala receives more rainfall from the anti-monsoon than any other region in Sri Lanka. From December to February, which correspond to the North-East monsoon and its aftermath, Ritigala experiences the highest rainfalls of Sri Lanka’s dry zone, about 125 mm per month. Clouds can often be seen clinging at the peak during every season of the year. This contributes to a wet microclimate near the summit, which is the reason why many rare species occur in the hills of Ritigala, also some species otherwise only found in the highlands. The high vapor condensation keeps the soil moist even when the plains are in drought in August and September.

The entire Ritigala mountain range consists of four peaks covered by dense forest. The forested mountain massif measures about 6 km from north to south and 3 km from east to west. An area of about 1,500 hectare was declared a Strict Nature Reserve, administered by both the Forest Department the Department of Wildlife of Sri Lanka, as threatened species such as leopards and sloth bears also occur in the sanctuary.

Three neighbouring peaks to the east of Ritigala Kanda form Andiyakanda-henne group. The valley in between is called Veval-thenne. It is home to a spring never drying up. Further north are three more peaks, all of which reach more than 700 m. The steep chasm that separates them from the Ritigala Kanda collects plenty of water during the local rainy season in late autumn and early winter of the northern hemisphere. The stream from this chasm is one of the two tributaries of the Banda Pokuna in the monastic area at the western base of the mountain range. Being the coolest and area in the northern plains of the island and rich in water, Ritigala was a place chosen by the British to establish a sanatorium in the late 19th century.

Ritigala receives more rainfall from the anti-monsoon than any other region in Sri Lanka. From December to February, which correspond to the North-East monsoon and its aftermath, Ritigala experiences the highest rainfalls of Sri Lanka’s dry zone, about 125 mm per month. Clouds can often be seen clinging at the peak during every season of the year. This contributes to a wet microclimate near the summit, which is the reason why many rare species occur in the hills of Ritigala, also some species otherwise only found in the highlands. The high vapor condensation keeps the soil moist even when the plains are in drought in August and September.

Flora of Ritigala

strangler fig in Ritigala

strangler fig in Ritigala

As the climate in heights of more than 600 m is in sharp contrast to that at the base of the Ritigala mountain range, with an intermediate vegetation at the slopes, the variety of plant species in the Ritigala forests is extraordinarily high. 400 species have been recorded, more speciea occur near the summit than near the plains. Particularly the upper reaches of the mountain are home to an extraordinarily vigorous flora rich in unusual plants and herbs, making the Ritigala range a bio diversity hot spot. This is why a Strict Nature Reserve was declared by the British colonial administration in 1941.

Wild orchids are kind of landmark plants of Ritigala’s forests. Few places in the Island can boost such a wealth of orchids as the summit of Ritigala. About 200 species of Ayurvedic herbs are found in abundance in higher elevations. Three plant species are said to be endemic to Ritigala, namely Madhuca clavata, Coleus elongatus, and Thunbergia fragrans var-parviflora. Some more species are extremely rare and almost extinct in other areas.

In 1889, Henry Trimen became the first modern botanist to investigate Ritigala. He published his record “Note on the Botany of Ritigala” in Journal Vol. XL, No. 39, 1889 of the Royal Asiatic Society, Ceylon Branch. The same volume also contained the papers “A Visit to Ritigala, in the North-Central Province” by Mr. A. P. Green and “Etymo-logical and Historical Notes on Ritigala” by Mr. D. M. de Zilva Wickremasinghe. His visit to Ritigala inspired Heny Trimen to do more research on the botany of the island, the result of which was the then standard reference “Handbook to the Flora of Ceylon”, published in 1893.

Particularly, the mini-plateau has a pocket of vegetation that is quite distinct from flora of the surrounding dry-zone and even of the forests at the slopes. Like in Sri Lanka’s montane cloud forest, there are stunted trees festooned with hanging moss. In 1906, the botanist J. C. Willis recorded 144 plant species within the small range of 30 meters from the summit, of which only 41 species occur typically in Sri Lanka’s dry zone, whereas the other 103 were wet-zone species. A small tree endemic to Sri Lanka and common otherwise in wet lowland and montane zones is Pittosporum zeylanicum, known as Ketiya or Ketuwa in Sinhala also occurs on the small summit plateau of Ritigala. A rather rare but typical tree of Sri Lanka’s rocky dry zone occuring at the bottom of the Ritigala Forest is the Hill Mango (Commiphora caudata), a deciduous tree growing about 15 meters tall. This tree is sometimes harvested from the wild for local Ayurvedic use and can occasionally be seen as ornamental or avenue tree in populated areas.

In order to protect the biodiversity of this highly sensitive ecosystems, cooperation with inhabitants of peripheral villages of the Ritigala Strict Nature Reserve is of utmost importance. There are 14 villages in the vicinity of Ritigala, inhabited by 6000 people, many belonging to the Tamil and Muslim minorities. 80% of the villagers are farmer families, who can harvest rice only once a year, which means that they are without work and income during a few months every year. They are tempted to be engaged in ecological depletion or exploitation of the “green gold” of Ritigala. Precious timber growing at the western slopes of the Ritigala range has fallen victim to illegal logging. Some medicinal herbs achieve high prices, too. That’s why state-funded projects of the nature conservation authorities provide opportunities, especially for women, to engage in sustainable income-generating activities, by cultivate Ayurvedic plants at village centres instead of collecting them from the sanctuary. The authorities also helped to reactivate ancient irrigation tanks in order to enhance the paddy production. In ancient times, much more tanks were in use than today, The surroundings of Ritigala seem to have been more densely populated in antiquity.

Wild orchids are kind of landmark plants of Ritigala’s forests. Few places in the Island can boost such a wealth of orchids as the summit of Ritigala. About 200 species of Ayurvedic herbs are found in abundance in higher elevations. Three plant species are said to be endemic to Ritigala, namely Madhuca clavata, Coleus elongatus, and Thunbergia fragrans var-parviflora. Some more species are extremely rare and almost extinct in other areas.

In 1889, Henry Trimen became the first modern botanist to investigate Ritigala. He published his record “Note on the Botany of Ritigala” in Journal Vol. XL, No. 39, 1889 of the Royal Asiatic Society, Ceylon Branch. The same volume also contained the papers “A Visit to Ritigala, in the North-Central Province” by Mr. A. P. Green and “Etymo-logical and Historical Notes on Ritigala” by Mr. D. M. de Zilva Wickremasinghe. His visit to Ritigala inspired Heny Trimen to do more research on the botany of the island, the result of which was the then standard reference “Handbook to the Flora of Ceylon”, published in 1893.

Particularly, the mini-plateau has a pocket of vegetation that is quite distinct from flora of the surrounding dry-zone and even of the forests at the slopes. Like in Sri Lanka’s montane cloud forest, there are stunted trees festooned with hanging moss. In 1906, the botanist J. C. Willis recorded 144 plant species within the small range of 30 meters from the summit, of which only 41 species occur typically in Sri Lanka’s dry zone, whereas the other 103 were wet-zone species. A small tree endemic to Sri Lanka and common otherwise in wet lowland and montane zones is Pittosporum zeylanicum, known as Ketiya or Ketuwa in Sinhala also occurs on the small summit plateau of Ritigala. A rather rare but typical tree of Sri Lanka’s rocky dry zone occuring at the bottom of the Ritigala Forest is the Hill Mango (Commiphora caudata), a deciduous tree growing about 15 meters tall. This tree is sometimes harvested from the wild for local Ayurvedic use and can occasionally be seen as ornamental or avenue tree in populated areas.

In order to protect the biodiversity of this highly sensitive ecosystems, cooperation with inhabitants of peripheral villages of the Ritigala Strict Nature Reserve is of utmost importance. There are 14 villages in the vicinity of Ritigala, inhabited by 6000 people, many belonging to the Tamil and Muslim minorities. 80% of the villagers are farmer families, who can harvest rice only once a year, which means that they are without work and income during a few months every year. They are tempted to be engaged in ecological depletion or exploitation of the “green gold” of Ritigala. Precious timber growing at the western slopes of the Ritigala range has fallen victim to illegal logging. Some medicinal herbs achieve high prices, too. That’s why state-funded projects of the nature conservation authorities provide opportunities, especially for women, to engage in sustainable income-generating activities, by cultivate Ayurvedic plants at village centres instead of collecting them from the sanctuary. The authorities also helped to reactivate ancient irrigation tanks in order to enhance the paddy production. In ancient times, much more tanks were in use than today, The surroundings of Ritigala seem to have been more densely populated in antiquity.

Fauna of Ritigala

Besides leopards and sloth bears, also wild elephants occur in the hills of Ritigala, not only in the surrounding plains. Wildlife department rangers have been fatally wounded in the forests by the wild elephants. That’s another reason, why tourists visiting the archaeological site are not allowed to climb the mountain.

However, some other animals can be spotted within the archeological area, too. Ritigala is rich in bird species, some of them are endangered.

The mountain is home to birds of prey such as the Black eagles (Ictinaetus malaiensis), a common Southasian raptor, the flight silhouette of which is easily identified by a narrowing at the base of wing. Other common large birds typical of South Asia and often seen in Ritigala are the Indian grey hornbill (Ocyceros birostris) and Malabar pied hornbill (Anthracoceros coronatus). Quite common birds endemic to the island are the Sri Lanka spurfowl (Galloperdix bicalcarata) and the Spot-winged thrush (Geokichla spiloptera).

However, some other animals can be spotted within the archeological area, too. Ritigala is rich in bird species, some of them are endangered.

The mountain is home to birds of prey such as the Black eagles (Ictinaetus malaiensis), a common Southasian raptor, the flight silhouette of which is easily identified by a narrowing at the base of wing. Other common large birds typical of South Asia and often seen in Ritigala are the Indian grey hornbill (Ocyceros birostris) and Malabar pied hornbill (Anthracoceros coronatus). Quite common birds endemic to the island are the Sri Lanka spurfowl (Galloperdix bicalcarata) and the Spot-winged thrush (Geokichla spiloptera).

|

Typical reptiles are Agamas, often mistakenly called “iguanas”, the latter occuring only in the Americas. Though chameleons occur in India and Sri Lanka, too, one being endemic to Sri Lanka (Chameleo zeylanica), they are not as frequently seen as in Africa and much less common than Agamas. Colourful reptiles in Sri Lanka are almost always Agamas, which form a distinct family. Usually, agamas are smaller and leaner than chameleons. Like chameleons, they are able to change their colours. Indeed, some Agama species are even more opalescent and can change the colour more quickly than chameleons.

|

Legends surrounding Ritigala

Ritigala, the isolated mountain amidst the plains of the former heartland of the ancient Sinhalese civilization, is surrounded by legends.

For instance, the Ritigala ridge is believed to be haunted by the island’s most-feared demon, Maha Sona, chief of 30,000 demons, who is the surviving spirit of Ritigala Jayasena, a famous giant who was 37 m tall. The name Maha Sona simply translates to “big demon”. Maha Sona is said to kill people by crushing their shoulders or striking them between them and to cause numerous diseases by posessing people and to be able to influence the afterlife in an evil way. When Maha Sona had been a giant in his human form as Ritigala Jayasena, he once was drunken and offended one of the ten heroic Giant Warriors of King Dutugemunu, The offended giant then decapitated him in a duel. When a god tried to revive the body, he was not able to find the correct head in time and had replace it. Ritigala Jayasena, coming to life again as Maha Sona, hence found himself with the head of an animal. Usually he is portrayed with the head of a bear.

One main theme of the legends surrounding Ritigala is the abundance of medicinal herbs occuring on the mountain. A specific herb known as Sansevi is believed to have the power of curing all human pain, corresponding the Sanjeevani known from Indian mythology. All vegetation of Ritigala is protected by demons called Yakkhas in Sri Lankan mythology. One story has it that a peasant once went astray in the forest and climbed higher and higher, because he was surprised to hear the sounds of a village in the mountain region of Ritigala, He was able to hear barking dogs and playing children. But when he approached the the settlement, it turned out to be inhabited by demons instead of human beings. One of the demons gave him food, Out of fear, the peasant did not dare to touch the meal. He started eating only after the demon had disappeared. The demon was one of the guardians of the Ritigala mountain. And he had said: The visitor is allowed to eat but not allowed to remove anything from the mountain. When the peasant returned home, he told his story to the villagers. And ever since, the herbs growing on the mountain and all anmils living thera have been considered to be taboo.

The foot of the Ritigala mountain is also believed to have been the battlefield where Prince Pandukhabaya once defeated and killed his maternal uncles except from Abhaya, who was a righteous person who had protected him, and his own wife’s father. Pandukabhaya afterwards was crowned and was the first Sinhalese king to choose Anuradhapura as his capital.

For instance, the Ritigala ridge is believed to be haunted by the island’s most-feared demon, Maha Sona, chief of 30,000 demons, who is the surviving spirit of Ritigala Jayasena, a famous giant who was 37 m tall. The name Maha Sona simply translates to “big demon”. Maha Sona is said to kill people by crushing their shoulders or striking them between them and to cause numerous diseases by posessing people and to be able to influence the afterlife in an evil way. When Maha Sona had been a giant in his human form as Ritigala Jayasena, he once was drunken and offended one of the ten heroic Giant Warriors of King Dutugemunu, The offended giant then decapitated him in a duel. When a god tried to revive the body, he was not able to find the correct head in time and had replace it. Ritigala Jayasena, coming to life again as Maha Sona, hence found himself with the head of an animal. Usually he is portrayed with the head of a bear.

One main theme of the legends surrounding Ritigala is the abundance of medicinal herbs occuring on the mountain. A specific herb known as Sansevi is believed to have the power of curing all human pain, corresponding the Sanjeevani known from Indian mythology. All vegetation of Ritigala is protected by demons called Yakkhas in Sri Lankan mythology. One story has it that a peasant once went astray in the forest and climbed higher and higher, because he was surprised to hear the sounds of a village in the mountain region of Ritigala, He was able to hear barking dogs and playing children. But when he approached the the settlement, it turned out to be inhabited by demons instead of human beings. One of the demons gave him food, Out of fear, the peasant did not dare to touch the meal. He started eating only after the demon had disappeared. The demon was one of the guardians of the Ritigala mountain. And he had said: The visitor is allowed to eat but not allowed to remove anything from the mountain. When the peasant returned home, he told his story to the villagers. And ever since, the herbs growing on the mountain and all anmils living thera have been considered to be taboo.

The foot of the Ritigala mountain is also believed to have been the battlefield where Prince Pandukhabaya once defeated and killed his maternal uncles except from Abhaya, who was a righteous person who had protected him, and his own wife’s father. Pandukabhaya afterwards was crowned and was the first Sinhalese king to choose Anuradhapura as his capital.

Excursus: Pandukabhaya

Pandukhabya’s mother was Ummada Chitta. The meaning of her name is "overwhelming beauty”. She was the daughter of Sri Lanka’s second ruler, King Panduvasudeva. The couple had ten sons. When a sage prophesied that Ummada Chitta’s son would kill nine of his uncles and claim the throne, nine brothers pledged King Panduvasudeva to kill his daughter. However, But Abhaya opposed this ambition, and Ummada Chitta was spared and hidden in a tower to prevent her from intercourse with males. As the story must unfold, a young man managed to get access to her and they had a son, who was named Pandukabhaya. To prevent him from being killed, Ummada Chitta claimed to have born a daughter and exchange babies with another woman who ideed had given birth to a girl that very same day. When the hidden prince grew up among villagers, the fame of his noble attitudes came to the ears of his uncles, whose suspicion was risen. Several times they attempted to kill that noble young men, Pandukabhaya. Once he was old enough to become king, he started to fight against his uncles to gain the Sinhalese throne. Eight of his ten uncles were killed in the long-lasting war, the decisive battle took place near Labugamaka (present-day Labunoruwa) on the north-west slope of the Ritigala ridge. Local legends have it that Pandukhabaya was assisted by the Yakkha demons of the Ritigala mountain during his battles against his uncles.

Hanuman's leap to the Himalayas

There is a famous legend explaining Ritigala's abundance in plants used in Ayurvedic treatments. This local legend, though not completely identical with the story line of the Indian epic, ties the origin of the mountain to an episode of the Ramayana epic. This legend is appealing and of course cannot remain untold in our Ritigala article:

In the battle against the demon army of the demon king Ravana on the island of Lanka, in which Rama and his entourage fought for the liberation of his wife Sita, Rama's brother Lakshmana, the second great hero of the epic, was severely injured by a magic arrow. Lakshmana was unconscious and about to die, as the wound could not be healed. His death threatened to be a disaster for the outcome of the entire campaign: The imminent death of his brother Lakshmana already plunged Rama so deeply into grief that he saw his powers dwindling, becoming unable to continue the fight.

Preventing this terrible end of the story of the liberation fight for Sita - which too would habe been disastrous for the restoration of the entire world's Dharma - proved to be extremely difficult, because no helping medicine was available on the entire island of Lanka. Just four herbs that can only be found in the Himalayas were said to have the power to heal Lakshmana's injuries.

Therefore, the monkey leader Hanuman was sent to bring these medicinal herbs from the Himalayas to Lanka. Hanuman makes a giant leap through the air into the Himalayas, no problem for him. However, arriving there, he faces an almost insurmountable problem: He simply cannot find the herbs, even though they are actually in this mountain area he is visiting. Hanuman finally solves this problem by breaking out of the Himalayas the entire mountain range, along with all the medicinal herbs, to bring him, trapped under his tail, through the air to the island of Lanka. As far as told here, this is the same story in the Indian Ramayana epic and in the Sri Lankan mythology of Ritigala.

But local tradition has it: On the way to Rama and Lakshmana on the battlefield in Lanka, a piece of the Himalaya slips away and falls into the sea onto the island, where it is broken into three parts. One of these three Himalaya rocks now, not surprisingly, is believed to be Ritigala.

In the battle against the demon army of the demon king Ravana on the island of Lanka, in which Rama and his entourage fought for the liberation of his wife Sita, Rama's brother Lakshmana, the second great hero of the epic, was severely injured by a magic arrow. Lakshmana was unconscious and about to die, as the wound could not be healed. His death threatened to be a disaster for the outcome of the entire campaign: The imminent death of his brother Lakshmana already plunged Rama so deeply into grief that he saw his powers dwindling, becoming unable to continue the fight.

Preventing this terrible end of the story of the liberation fight for Sita - which too would habe been disastrous for the restoration of the entire world's Dharma - proved to be extremely difficult, because no helping medicine was available on the entire island of Lanka. Just four herbs that can only be found in the Himalayas were said to have the power to heal Lakshmana's injuries.

Therefore, the monkey leader Hanuman was sent to bring these medicinal herbs from the Himalayas to Lanka. Hanuman makes a giant leap through the air into the Himalayas, no problem for him. However, arriving there, he faces an almost insurmountable problem: He simply cannot find the herbs, even though they are actually in this mountain area he is visiting. Hanuman finally solves this problem by breaking out of the Himalayas the entire mountain range, along with all the medicinal herbs, to bring him, trapped under his tail, through the air to the island of Lanka. As far as told here, this is the same story in the Indian Ramayana epic and in the Sri Lankan mythology of Ritigala.

But local tradition has it: On the way to Rama and Lakshmana on the battlefield in Lanka, a piece of the Himalaya slips away and falls into the sea onto the island, where it is broken into three parts. One of these three Himalaya rocks now, not surprisingly, is believed to be Ritigala.

Variants of the Ramayana's story

As said, the local legends of Sri Lanka are somewhat different from the story of the Indian Ramayana epic. Already within the original Sanskrit version of the Ramayana composed by Valmiki, there are two versions of the story how parts of the Himalayas were brought to Sri Lanka.

Both can be found in the Yuddha Kanda, the "war book", which is the story of the battle on the island of Lanka, the climax of the entire epic. In Chapter 102 of the Yuddha Kanda, the avovementioned episode is told in which Lakshmana is almost killed. However, a very similar episode can already be found in Chapter 74. In this part of the story, it's not just Lakshmana who is terminally injured and unconscious, but Rama himself, too. Both "sons of Raghu" and furthermore almost their entire army of monkeys, all great heroes among them, who had been fighting on Rama's side, are almost incurably injured. In this case it is Jambavan, the leader of the bears, who sends Hanuman to fetch the only helping herbs from the Himalayas, while in chapter 102, Sushen, a leader of the monkeys, instructs Hanuman to get them from there.

Apart from the crucial supplement that chunks of the Himalayan massif fell down and remained on Sri Lanka, the local legends also differ in yet another respect from the original Ramayana story. And this aspect of the Ritigala legend actually is worth telling:

The reason for the absence of the four herbs in the Himalayas, which the Ramayana of the Valmiki indicates, is that they hide from the eyes of Hanuman or are hidden by the gods, probably because the supernatural powers of these plants shall be reserved solely for the gods. However, Ritigala's local legend knows another reason why Hanuman cannot find the herbs, one that may be somewhat more charming: The names of the four herbs that Hanuman had to fetch were exceptionally long and complicated. So not surprisingly, a slip-up occurs: Arriving in the Himalayas, Hanuman was not able to remember those difficult names any more. Hence, out of embarrassment, he took with him an entire mountain range, on which he knew the medicinal plants were growing.

Yet another variant of the same story is worth mentioning: Rama's army was too decimated in the battle to win the campaign for Sita's liberation. But, it is said, some Himalayan herbs could even bring the dead back to life. Since no one knows which specific herbs these are, Hanuman brings a whole segment of the Himalayas to Lanka. And there, fortunately, everyone recognizes the medicinal plants very easily, because the fallen ones are resurrected by already their smell, even before the entire chunk of the Himalayas has arrived. Incidentally, this version of the story can be linked to one specific aspect of chapter 74 of the Yuddha Kanda: there too it is the smell of the approaching medicinal plants alone that makes the wounded and unconscious heroes, including the monkey army, recover their strength.

Both can be found in the Yuddha Kanda, the "war book", which is the story of the battle on the island of Lanka, the climax of the entire epic. In Chapter 102 of the Yuddha Kanda, the avovementioned episode is told in which Lakshmana is almost killed. However, a very similar episode can already be found in Chapter 74. In this part of the story, it's not just Lakshmana who is terminally injured and unconscious, but Rama himself, too. Both "sons of Raghu" and furthermore almost their entire army of monkeys, all great heroes among them, who had been fighting on Rama's side, are almost incurably injured. In this case it is Jambavan, the leader of the bears, who sends Hanuman to fetch the only helping herbs from the Himalayas, while in chapter 102, Sushen, a leader of the monkeys, instructs Hanuman to get them from there.

Apart from the crucial supplement that chunks of the Himalayan massif fell down and remained on Sri Lanka, the local legends also differ in yet another respect from the original Ramayana story. And this aspect of the Ritigala legend actually is worth telling:

The reason for the absence of the four herbs in the Himalayas, which the Ramayana of the Valmiki indicates, is that they hide from the eyes of Hanuman or are hidden by the gods, probably because the supernatural powers of these plants shall be reserved solely for the gods. However, Ritigala's local legend knows another reason why Hanuman cannot find the herbs, one that may be somewhat more charming: The names of the four herbs that Hanuman had to fetch were exceptionally long and complicated. So not surprisingly, a slip-up occurs: Arriving in the Himalayas, Hanuman was not able to remember those difficult names any more. Hence, out of embarrassment, he took with him an entire mountain range, on which he knew the medicinal plants were growing.

Yet another variant of the same story is worth mentioning: Rama's army was too decimated in the battle to win the campaign for Sita's liberation. But, it is said, some Himalayan herbs could even bring the dead back to life. Since no one knows which specific herbs these are, Hanuman brings a whole segment of the Himalayas to Lanka. And there, fortunately, everyone recognizes the medicinal plants very easily, because the fallen ones are resurrected by already their smell, even before the entire chunk of the Himalayas has arrived. Incidentally, this version of the story can be linked to one specific aspect of chapter 74 of the Yuddha Kanda: there too it is the smell of the approaching medicinal plants alone that makes the wounded and unconscious heroes, including the monkey army, recover their strength.

Quotations from the Ramayana

from Yuddha Kanda chapter 74"The shades of falling night concealed

The carnage of the battle field, Which, hearing each a blazing brand, Hanúmán and Vibhíshan scanned, Moving with slow and anxious tread Among the dying and the dead. Sad was the scene of slaughter shown Where'er the torches' light was thrown. Here mountain forma of Vánars lay Whose heads and limbs were lopped away Arms legs and fingers strewed the ground, And severed heads lay thick around. The earth was moist with sanguine streams, And sighs were heard and groans and screams. There lay Sugríva still and cold, There Angad, once so brave and bold. There Jámbaván his might reposed, There Vegadars'í's eyes were closed; There in the dust was Nala's pride, And Dwivid lay by Mainda's side. Where'er they looked the ensanguined plain Was strewn with myriads of the slain; They sought with keenly searching eyes King Jámbaván supremely wise. His strength had failed by slow decay, And pierced with countless shafts he lay. They saw, and hastened to his side, And thus the sage Vibhíshan cried: 'Thee, monarch of the bears, we seek: Speak if thou yet art living, speak.' Slow came the aged chief's reply; Scarce could he say with many a sigh: 'Torn with keen shafts which pierce each limb, My strength is gone, my sight is dim; Yet though I scarce can raise mine eyes. Thy voice. O chief. I recognize. O, while these ears can hear thee, say, Has Hanumán survived this day?' 'Why ask,' Vibhíshan cried,' for one Of lower rank, the Wind-God's son? Hast thou forgotten, first in place, The princely chief of Raghu's race? Can King Sugríva claim no care, And Angad, his imperial heir?' 'Yea, dearer than my noblest friends Is he on whom our hope depends. For if the Wind-God's son survive, All we though dead are yet alive. But if his precious life be fled Though living still we are but dead: He is our hope and sure relief.' Thus slowly spoke the aged chief: Then to his side Hanúmán came, And with low reverence named his name. Cheered by the face he longed to view The wounded chieftain lived anew. 'Go forth,' he cried, 'O strong and brave, And in their woe the Vánars save. 'No might but thine, supremely great, May help us in our lost estate, The trembling bears and Vánars cheer, Calm their sad hearts, dispel their fear. Save Raghu's noble sons, and heal The deep wounds of the winged steel. High o'er the waters of the sea To far Himálaya's summits flee. Kailása there wilt thou behold, Aud Rishabh, with his peaks of gold. Between them see a mountain rise Whose splendour will enchant thine eyes; His sides are clothed above, below, With all the rarest herbs that grow. Upon that mountain's lofty crest Four plants, of sovereign powers possessed, Spring from the soil, and flashing there Shed radiance through the neighbouring air. One draws the shaft: one brings again The breath of life to warm the slain; One heals each wound; one gives anew To faded cheeks their wonted hue. Fly, chieftain, to that mountain's brow And bring those herbs to save us now.' Hanúmán heard, and springing through The air like Vishnu's discus 1b flew. The sea was passed: beneath him, gay With bright-winged birds, the mountains lay, And brook and lake and lonely glen, And fertile lands with toiling men. On, on he sped: before him rose The mansion of perennial snows. There soared the glorious peaks as fair As white clouds in the summer air. Here, bursting from the leafy shade, In thunder leapt the wild cascade. He looked on many a pure retreat Dear to the Gods' and sages' feet: The spot where Brahmá dwells apart, The place whence Rudra launched his dart; Vishnu's high seat and Indra's home, And slopes where Yama's servants roam. There was Kuvera's bright abode; There Brahma's mystic weapon glowed. There was the noble hill whereon Those herbs with wondrous lustre shone. And, ravished by the glorious sight, Hanúmán rested on the height. He, moving down the glittering peak, The healing herbs began to seek: But, when he thought to seize the prize, They hid them from his eager eyes. Then to the hill in wrath he spake: 'Mine arm this day shall vengeance take, If thou wilt feel no pity, none, In this great need of Raghu's son.' He ceased: his mighty arms he bent And from the trembling mountain rent His huge head with the life it bore, Snakes, elephants, and golden ore. O'er hill and plain and watery waste His rapid way again he traced. And mid the wondering Vánars laid His burthen through the air conveyed. The wondrous herbs' delightful scent To all the host new vigour lent. Free from all darts and wounds and pain The sons of Raghu lived again, And dead and dying Vánars healed Rose vigorous from the battle field." |

from Yuddha Kanda chapter 102"But Ráma, pride of Raghu's race,

Gazed tenderly on Lakshman's face, And, as the sight his spirit broke, Turned to Sushen and sadly spoke: 'Where is my power and valour? how Shall I have heart for battle now, When dead before my weeping eyes My brother, noblest Lakshman, lies? My tears in blinding torrents flow, My hand unnerved has dropped my bow The pangs of woe have blanched my cheek. My heart is sick, my strength is weak. Ah me, my brother! Ah, that I By Lakshman's side might sink and die Life, war and conquest, all are vain If Lakshman lies in battle slain. Why will those eyes my glances shun? Hast thou no word of answer, none? Ah, as thy noble spirit flown And gone to other worlds alone? Could thou not let thy brother seek Those worlds with thee? O speak, O speak! Rise up once more, my brother, rise, Look on me with thy loving eyes. Were not thy steps beside me still In gloomy wood, on breezy hill? Did not thy gentle care assuage Thy brother's grief and fitful rage? Didst thou not all his troubles share, His guide and comfort in despair?' As Ráma, vanquished, wept and sighed The Vánar chieftain thus replied: 'Great Prince, unmanly thoughts dismiss, Nor yield thy soul to grief like this, In vain those burning tears are shed: Our glory Lakshman is not dead. Death on his brow no mark has set, Where beauty's lustre lingers yet. Clear is the skin, and tender hues Of lotus flowers his palms suifuse. O Ráma, cheer thy trembling heart; Not thus do life and body part, Now, Hanumán, to thee I speak: Hie hence to tall Mahodaya's 1 peak Where herbs of sovereign virtue grow Which life and health and strength bestow Bring thou the leaves to balm his pain, And Lakshman shall be well again.' He ceased: the Wind-God's son obeyed Swift through the clouds his way he made. He reached the hill, nor stayed to find The wondrous herbs of healing kind, From its broad base the mount he tore With all the shrubs and trees it bore, Sped through the clouds again and showed To wise Sushen his woodv load. 2 Sushen in wonder viewed the hill, And culled the sovereign salve of ill. Soon as the healing herb he found, The fragrant leaves he crushed and ground. Then over Lakshman's face he bent, Who, healed and strengthened by the scent Of that blest herb divinely sweet, Rose fresh and lusty on his feet" The English verses of both chapters (Yuddha Kanda 74 and 102)

are cited from: Ralph T. H. Griffith, The Ramayan of Valmiki, London 1870-1874 |

Excursus: Mount Dronagiri

In Hindu mythology, Mount Dronagiri is the home of the Sanjeewani herb. According to chapter 102 of the Yuddha Kanda, the name of mountain in the Himalayas said to be the home of the medicinal herbs is 'Mahodaya', the mountain's location mentioned there is between Kailash and Rishab. Unlike the famous Kailash, the Rishab is not clearly determinable in today's geography. Even less clear is the answer to the question, which mountain in between Hanuman was carried to the island of Lanka? In Indian traditions, the Mahodaya mentioned in the Ramayana is often identified with the mythical mountain Dronagiri (Drongiri). This is said to be today's Dunagiri, a side mountain of Nanda Devi, India's highest peak outside Kashmir. Dronagiri alias Dunagiri is located in the district of Almora in India's Uttarakhand State. However, other regions in the Himalayas also claim to be the mythical Dronagiri, for example Dhauladhar in the state of Himachal Pradesh.

Associated with the name of the mountain as Dronagiri (instead of Mahodaya) is another shift away from the origianl story found in the Ramayana of Valmik. This variant is very common among Hindus. Their mythological beliefs have it that instead of four plants there is only one, which could cure Lakshman, namely the fabled Sanjweewani, known in the Ritigala legend as 'Sansevi', anyway a single plant species that can cure all diseases. Regrettably, the mountain spirits of Ritigala strictly guard this plant, which heals every disease and gives a long life, and deny us access to it. Actually, it's so well protected by them that human researchers have not been able to discover it yet.

However, we definitely know now, why there are so many rare medicinal herbs in Ritigala. They came from the Himalayas as the entire mountain of Ritigala is a fallen piece of the mythical Himalayan mountain Dronagiri

Sanjeewani herb

There are various transliterations of India’s most famous mytholigical herb: Sanjivani, Sanjivini, Sanjiwani, Sanjiwini, Sanjeevani, Sanjeevini and so on. In Hindu mythology, Sanjeewani is a medicinal herb with supernatural powers and glowing in the dark. Sanjeewani is believed to cure all diseases. And some medicines prepared from this herb are said to have so much healing power to reanimate the bodies of the dead.

Sanjeewani is actually used as a name of a specific medicinal plant, Selaginella bryopteris. This non-mythical Sanjeewani herb is a lithophytic plant actually used medicinally in India, particularly by tribes in central India. It is more common in the Arawali Mountains than in the Himalayas. This non-mythical Sanjeewani plant can promote growth and is used as protection against heat shock, ultraviolet rays and oxidative stress.

Sanjeewani drops

According to local legends, Hanuman lost some chunks of Mount Dronagiri during his jump through the air from the Himalayas to the island of Lanka. Those places where fragments of the Himalaya mountain fell down are called “Sanjeewani drops”. Usually five places in Sri Lanka are said to be Sanjeewani drops. Some pious Hindu pilgrims from India like to visit them during a Ramayana Yatra. However, one of them is Kachchateevu island in the Palk Strait, which can usually be visited only during the St Antony's church festival. Four places on Sri Lanka's mainland claim to be Sanjeewani drops and can be reached throughout the year: Thalladi close to the Thiruketeeshwaram temple is near Mannar Island, but on Sri Lanka's mainland, it's not a mountain but a wetland area. Rumassala is a rocky promontory in Unawatuna near Galle. Dolukanda is the hill at the ancient monastery of Arankale, which is quite similar to Ritigala. Sri Lanka's major Sanjeewani drop of course is Ritigala. Though all Sri Lankan Sanjeevani drops do not harbour specific Himalayan fauna, they are known for their remarkable abundance in medicinal herbs.

By the way, Sri Lanka is not the only country claiming to have Sanjeewani drops. In India's southernmost state, Tamil Nadu, there are at least three hills which are also believed to be Sanjeewani drops, namely Sanjeevi Hill near Rajapalayam in Virudhunagar District, Sathuragiri Hills in Madurai District and Sirumalai in Dindigul District.

Name of Ritigala

The etymology of the modern name “Ritigala” is not entirely clear. “Gala” is the common word for “rock”. The modern Sinhala word “Riti” acould refer to the evergreen Upas tree (Antiaris toxicaria, also known as bark cloth tree or false iroko), which occurs at the slopes of the hill. Its Sinhalese name “Riti” means “pole” and is now used for the Upas tree due to its height of over 40 m.

The ancient name known of Ritigala known from the Mahavamsa is Arittha Pabbata, which can be translated to both “dreadful hill” or “safe mountain”. The name could refer to the Yakkha demons believed to live in the Ritigala hills and protecting it. Or it alludes to the fact that Ritigala served as refuge of several princes and kings in the course of the centuries. They often used the forests of Ritigala as a base from where they launched campaigns to gain or regain control of Anuradhapura.

"Arittha" was also the name of a minister, who after the conversion of Sri Lanka’s Anuradhapura Kingdom to Buddhism, was sent as an envoy to the Indian Emperor Ashoka, in order to gain a sapling of the Sacred Bodhi-tree. One legend has it, that after his return with the Bo-tree to Sri Lanka, Arittha settled down in the remote forests of this hill to live a secluded life. The Mahavamsa, Sri Lanka’s “Great Chronicle” from the 5th century, mentions Arittha Pabbata several times. It’s second part, which was compiled several centuries later on, also mentions the hill. For example, in the ninth century AD, King Sena made endowment of the monastery, a larger complex higher up the slope for a group of Buddhist ascetics called the Pansukulikas.

The name Arishtha denominating a mountain on the island of Lanka is already known from the Indian Ramyana epic, but this name seems not to refer to Ritigala.

The ancient name known of Ritigala known from the Mahavamsa is Arittha Pabbata, which can be translated to both “dreadful hill” or “safe mountain”. The name could refer to the Yakkha demons believed to live in the Ritigala hills and protecting it. Or it alludes to the fact that Ritigala served as refuge of several princes and kings in the course of the centuries. They often used the forests of Ritigala as a base from where they launched campaigns to gain or regain control of Anuradhapura.

"Arittha" was also the name of a minister, who after the conversion of Sri Lanka’s Anuradhapura Kingdom to Buddhism, was sent as an envoy to the Indian Emperor Ashoka, in order to gain a sapling of the Sacred Bodhi-tree. One legend has it, that after his return with the Bo-tree to Sri Lanka, Arittha settled down in the remote forests of this hill to live a secluded life. The Mahavamsa, Sri Lanka’s “Great Chronicle” from the 5th century, mentions Arittha Pabbata several times. It’s second part, which was compiled several centuries later on, also mentions the hill. For example, in the ninth century AD, King Sena made endowment of the monastery, a larger complex higher up the slope for a group of Buddhist ascetics called the Pansukulikas.

The name Arishtha denominating a mountain on the island of Lanka is already known from the Indian Ramyana epic, but this name seems not to refer to Ritigala.

Ritigala jungle as hiding place of kings

The first example of a hero taking refuge at Ritigala ist one of Sri Lanka’s most legendary kings, Pandukabhaya (4th century B.C.), who later on was the first monarch who chose Anuradhapura as his capital. It is in connection with Pandukabhaya that the Arittha mountain is mentioned in the ancient Mahavamsa for the first time. The insurgent Prince Pandukabhaya gathered an army of Yakkha-demons at this place to fight against his uncles, who were the heirs to the Sinhalese throne (see grey box). The historical kernel of the Pandukabhaya legend might be, that indigenous people, usually called demons in the chroncles, soon after the arrival of the Sinhalese played a prominent role in establishing Sinhalese rule in Anuradhapura. Immediately after defeating the uncles’ army and piling up the skulls of the fallen soldiers with the skulls of eight uncles on top, as the 10th chapter of the Mahavamsa narrates, Pansukabhaya proceeded to Anuradhapura, where he built a first tank, a major project for the development of the city and of paradigmatic significance for the hydraulic civilisatition ot the ancient Anuradhapura kingdom. Local legend has it, that Pandukhabhaya also established the Banda Pokuna, the large bathing pond at the foot of the Ritigala mountain, though this tank is actually several centuries younger.

Since the earliest times of the Anuradhapura kingdom, Ritigala as the “Arittha Pabhatha”, the “refuge-hill”, is believed to have been the hiding place of several important conquerers or kings, when they advanced the capital.

Ritigala is also believed to have been a site of recoup during the war of no less than King Dutthagamani, who came from the southern kingdom of Ruhuna (161-136 BC) to regain Sinhalese and Buddhist control of Anuradhapura. However, the mountain mentioned as the army camp of Sri Lanka’s national hero during his campaign against the Tamil King Elara of Anuradhapura is named Kasa in the 25th chapter of the Mahavamsa. The name Arittha does not occur in this context.

Another well known king from Sri Lanka’s history is Mahasena, though not famous as a Buddhist hero but a heretic, because he favoured the Mahayanist school. Mahasena is famed for the construction of several of Sri Lanka’s most significant irrigation reservoirs. He is said to have lived and meditated in the jungles at the slopes of Ritigala during the period of construction of the Minneriya tank

It’s likely that indeed several kings visited Ritigala, due to the legend of King Pandukabhaya, whom they considered to be their progenitor. In a sense, Ritigala was the mountain of origin of the lineage of Anuradhapura kings, similar to the Mihintale hills, which were considered to be the origin of the Buddhist monastic lineage.

The second major part or sequel of the Mahavamsa, sometimes referred to as Chulavamsa, mentions the Arittha mountain in connection with a king of the 7th century. Prince Jetthatissa, also spelt as Jettha Tissa, revolted against his brother, King Aggabodhi III. Sirisangabo. When Aggabodhi III. Became king in Anuradhapura in 623, he appointed his brother Mana vice-king and commander in the southern principality of Rohana (Ruhuna). The other brother, Jetthatissa sojourned in the hillcountry those day and felt overlooked. Chulavamsa 44,86 reports, he advanced to the Arittha mountain and succeded in winning the locals for his campaign. History is being repeated. When the army of Anuradhapura’s king tried to conquer the rebel camp, the locals turned out to be victorious and Prince Jetthatissa captured the capital, wher he was crownd soon afterwards. However, his reign turned out to be short-lived. His brother, King Aggabodhi III Sirisanghabo, had fed to India, where he managed to hire an army of Tamil merceneries. Returning to Sri Lanka after only a few month, Aggabodhi defeated his brother in combat. In his hopeless position, Jetthatissa killed first some more Tamil attackers, before he decapitated himself on his royal elephant. He had advised his ministers, his wife should become a Buddhist nun and with her spiritual merits support the king. But when she heard about the circumstances of her husband’s death, sh died from a broken heart. Remarkably, the Chulavamsa is without taking of sides in this fratricidal war of succession. The chronicle credits both kings with meritoorious deeds, this means, both are praised for contributing to the sustainance of the Buddhist orders..

The entire 7th century saw several insurgencies and wars of succession. The rivalling claimants to the throne used to hire Tamil mercanaries from Southern India. This in turn resulted in Tamil revolts and occupations during this period of unrest. At times, the Tamil generals seemed to have been more powerful than the Sinhalese kings.

Ritigala became a hiding place of rebels again in recent history. In 1971, Sinhalese Marxist insurgents of the JVP youth movement found temporary sanctuary in the jungles of Ritigala during the last stages of their militant campaign. Only after several weeks of guerilla combat, this splinter cell was finally defeated by Sri Lanka’s security forces.

Since the earliest times of the Anuradhapura kingdom, Ritigala as the “Arittha Pabhatha”, the “refuge-hill”, is believed to have been the hiding place of several important conquerers or kings, when they advanced the capital.

Ritigala is also believed to have been a site of recoup during the war of no less than King Dutthagamani, who came from the southern kingdom of Ruhuna (161-136 BC) to regain Sinhalese and Buddhist control of Anuradhapura. However, the mountain mentioned as the army camp of Sri Lanka’s national hero during his campaign against the Tamil King Elara of Anuradhapura is named Kasa in the 25th chapter of the Mahavamsa. The name Arittha does not occur in this context.

Another well known king from Sri Lanka’s history is Mahasena, though not famous as a Buddhist hero but a heretic, because he favoured the Mahayanist school. Mahasena is famed for the construction of several of Sri Lanka’s most significant irrigation reservoirs. He is said to have lived and meditated in the jungles at the slopes of Ritigala during the period of construction of the Minneriya tank

It’s likely that indeed several kings visited Ritigala, due to the legend of King Pandukabhaya, whom they considered to be their progenitor. In a sense, Ritigala was the mountain of origin of the lineage of Anuradhapura kings, similar to the Mihintale hills, which were considered to be the origin of the Buddhist monastic lineage.

The second major part or sequel of the Mahavamsa, sometimes referred to as Chulavamsa, mentions the Arittha mountain in connection with a king of the 7th century. Prince Jetthatissa, also spelt as Jettha Tissa, revolted against his brother, King Aggabodhi III. Sirisangabo. When Aggabodhi III. Became king in Anuradhapura in 623, he appointed his brother Mana vice-king and commander in the southern principality of Rohana (Ruhuna). The other brother, Jetthatissa sojourned in the hillcountry those day and felt overlooked. Chulavamsa 44,86 reports, he advanced to the Arittha mountain and succeded in winning the locals for his campaign. History is being repeated. When the army of Anuradhapura’s king tried to conquer the rebel camp, the locals turned out to be victorious and Prince Jetthatissa captured the capital, wher he was crownd soon afterwards. However, his reign turned out to be short-lived. His brother, King Aggabodhi III Sirisanghabo, had fed to India, where he managed to hire an army of Tamil merceneries. Returning to Sri Lanka after only a few month, Aggabodhi defeated his brother in combat. In his hopeless position, Jetthatissa killed first some more Tamil attackers, before he decapitated himself on his royal elephant. He had advised his ministers, his wife should become a Buddhist nun and with her spiritual merits support the king. But when she heard about the circumstances of her husband’s death, sh died from a broken heart. Remarkably, the Chulavamsa is without taking of sides in this fratricidal war of succession. The chronicle credits both kings with meritoorious deeds, this means, both are praised for contributing to the sustainance of the Buddhist orders..

The entire 7th century saw several insurgencies and wars of succession. The rivalling claimants to the throne used to hire Tamil mercanaries from Southern India. This in turn resulted in Tamil revolts and occupations during this period of unrest. At times, the Tamil generals seemed to have been more powerful than the Sinhalese kings.

Ritigala became a hiding place of rebels again in recent history. In 1971, Sinhalese Marxist insurgents of the JVP youth movement found temporary sanctuary in the jungles of Ritigala during the last stages of their militant campaign. Only after several weeks of guerilla combat, this splinter cell was finally defeated by Sri Lanka’s security forces.

History of the Buddhist monastery of Ritigala

Ritigala was inhabited by reclusive Buddhist monks from the pre-Christian era onwards, as is indicated by Brahmi rock inscriptions, typically carved at the artificial drip-ledges of the natural caves. Similarly to other groups of rock shelters in Sri Lanka, several caves on the slopes of the Ritigale mountain were donated by laymen to those clerics who wanted to decote their lives to meditation. Before presenting his gift to the order, the donor drove away wild animals, bugs and snakes by fumigating the cave and cleaned the interior and plastered it with lime and carved out a drip-ledge above the entrance to prevent rain water from pouring into the cave. Sometimes the opening was walled for further protection of the monk’s cell.

King Suratissa

Suratissa (247-37 BC or later) is the first Anuradhapura king mentioned in the Mahavamsa who is credited with the foundation of a monastery at the Arittha mountain alias Ritigala. The 21st chapter of the Great Chronicle gives the name Makulaka of this Buddhist temple. Suratissa, after Uttiya and Mahasiva is the third brother following Devanampiya Tissa on the throne, who had introduced Buddhism as the state religion of the Anuradhapura Kingdom. This means, the chronicle attributes the Ritigala monastery to the first generation of Buddhist kings in Sri Lanka, indicating the high significance of the remote place in the jungles. Remnants of this first Buddhist temple at Ritigala have not yet been found. It may well be, that King Suratissa donated natural caves to the monks, instead of constructing edifices.

King Lanjatissa

An inscription found at one of the caves at Ritigala records that the monastery was founded by a king, who id identified with King Lanjatissa (119 – 109 BC). Lanjatissa, also known as Lajji Tissa, was the nephew of the famous King Dutthagamini. The 33rd chapter of the Mahavamsa credits Lanjatissa with the construction of the Arittha Viharaya, which might indicate that this was a distinct second monastery at the Arittha mountain alias Ritigala, apart from King Suratissa’s Makulaka temple. Remarkably the same verse reports, that King Lanjatissa distributed medicines to the monks in the villages, which may refer to the Ayurvedic herbs collected at Ritigala. Lanjatissa was eager to foster the Sangha, the Buddhist order, since his relationship with the clergy had not been cordial right from the beginning. When his father Saddhatissa had died, the Sangha interfered by declaring Lanjatissa’s younger brother Thulatthana king. Lanjatissa, who was absent from Anuradhapura those days, returned home and gained the throne forcefully after only 40 days. His brother came to death. That’s why the new king’s relationship to the Buddhist order was tense in the beginning. Increased support for the Sangha was a way for King Lanjatissa to reestablish a better cooperation between throne and clergy. Apart from restoration works in Anuradhapura, Lanjatissa also donated the Arittha and provided medicinal herbs.

Thirty of altogether 70 rock shelters at Ritigala carry ancient inscriptions in Brahmi characters. Many of them are from the centuries around the birth of Christ. It’s one inscription at the Andiyakanda massif that is attributed to Lanjatissa by modern scholars. The ancient text reads: “Cave of the great King Tissa, friend of gods, son of the great King Gamani Tissa, donated to the Sangha of the four quartes, now and in future”. It’s the only inscription from the Anuradhapura period which mentions one king being the son of another king. Gamani Tissa may refer to King Saddhatissa. It’s quite common that royal names in the chronicles differ from those in inscriptions. It’s known from inscriptions in Mihintale that Lanjatissa called himself Tissa and that Gamani Tissa was one of the royal names of his father Saddhatissa. According to Sri Lanka’s most renowned historian, Paranavitana. the rare case of a reference of a king to his royal father may indicate that his own authority was in doubt and had to be strengthened by proclaiming the authority of an undisputed predecessor and ancestor. This would be in accordance with the tensions and disputes concerning Lanjatissa’s succession to the throne, as reported in the Mahavamsa chapter 33. Besides inscriptional evidence from Mihintale, this is another reason why the quoted inscription mentioning a King Tissa as the donor is ascribed to Lanjatissa.

Thirty of altogether 70 rock shelters at Ritigala carry ancient inscriptions in Brahmi characters. Many of them are from the centuries around the birth of Christ. It’s one inscription at the Andiyakanda massif that is attributed to Lanjatissa by modern scholars. The ancient text reads: “Cave of the great King Tissa, friend of gods, son of the great King Gamani Tissa, donated to the Sangha of the four quartes, now and in future”. It’s the only inscription from the Anuradhapura period which mentions one king being the son of another king. Gamani Tissa may refer to King Saddhatissa. It’s quite common that royal names in the chronicles differ from those in inscriptions. It’s known from inscriptions in Mihintale that Lanjatissa called himself Tissa and that Gamani Tissa was one of the royal names of his father Saddhatissa. According to Sri Lanka’s most renowned historian, Paranavitana. the rare case of a reference of a king to his royal father may indicate that his own authority was in doubt and had to be strengthened by proclaiming the authority of an undisputed predecessor and ancestor. This would be in accordance with the tensions and disputes concerning Lanjatissa’s succession to the throne, as reported in the Mahavamsa chapter 33. Besides inscriptional evidence from Mihintale, this is another reason why the quoted inscription mentioning a King Tissa as the donor is ascribed to Lanjatissa.

King Sena I

Chapter 50 of Mahavamsa, belonging to its second part sometimes called Chulavamsa, tells us that in the 9th century AD, King Sena I (846-66) made additions to the Ritigala monastery by constructing a larger tank and a new complex higher up the slope. Sena I is well-known from Sri Lankan history, because during his reign the island suffered a major invasion carried out by the Southindian Pandya dynasty. The Anuradhapura kingdom seems to have recovered from this raid quickly, as the same king was able to support the Buddhist order soon afterwards:

|

“And he built, as it were by miracle, a great vihara at Arittha-pabbata, and endowed it with great possessions, and dedicated it to the Pansukulika brethren. And he gave to it also royal privileges and honours, and a great number of keepers for the garden, and servants, and artificers.“

(Mahavamsa/Chulavamsa 50,63-64) |

The cited verse mentions the Pansukulika fraternity, also transcribed Pamsukulika. It was an ascetic reform movement in the Buddhist Sangha. But it’s not entirely correct to call them sects that broke away Rather the Pamsukilikas formed branch or the main monasteries of Anuradhpura, particularly of the capital’s Abhayagiri congregation. The western monasteries in Anuradhapura and Ritigala alias Arittha Pabbata in some distance from the capital became the major monasteries of this Buddhist fraction. Ritigala being their largest monastic complex at all. It’s the ruins of this Pamsukulika monastery that the modern pilgrim can see today at the eastern slope of Ritigala. The name of their specific kind of monastic architecture is Padhanaghara Parivena.

Ritigala seems to have been abandoned during the 11th century, when the cultural heartland of the Sinhalese civilization was occupied by the Tamil dynasty of the Cholas from southern India. It was soon taken over by the jungle and largely forgotten till the ruined monastery was found and examined during the British colonial period.

Ritigala seems to have been abandoned during the 11th century, when the cultural heartland of the Sinhalese civilization was occupied by the Tamil dynasty of the Cholas from southern India. It was soon taken over by the jungle and largely forgotten till the ruined monastery was found and examined during the British colonial period.

Rediscovery of Ritigala

The monastic complex of Ritigala was rediscovered by the colonial surveyor James Mantell, who came here to establish a point of triangulation. Mantell mentioned the ruins in his report, which was published in 1872. Six years later, Mantell’s brother, also a surveyor, came to Ritigala, too. The British colonial administration planned to establish a sanatorium in a higher altitude in the dry zone. In 1893, Ritigala was explored by H.C.P. Bell, the first Commissioner of Archaeology of Ceylon.

Pamsukulika History