Isenbessagala, also spelt Isinbassagala, is a typical monadnock in Anuradhapura District, close to the border of the Northern Province. Isenbessagala, located 3.5 km north of Medawachchiya at the Kandy-Jaffna mainroad (A9), like many other gneiss rocks of Sri Lanka, has become a Buddhist monastery. A new temple is situated at the base of the hill, whereas the summit is crowned by a stupa. The contrast of dark gneiss of the natural rock and the shining white of a dagaba building on top of it is typical of Sri Lanka.

Isenbessagala claims to have been the first landing place of Missionary Mahinda, who introduced Buddhism to the island nation of Sri Lanka. This local legend is not narrated in the ancient chronicles. Mihintale 27 km further south is the venerated as the place where Monk Mahinda arrived, the son of India’s Emperor Ashoka. The legend of Isenbesssagala does not dare to dispute this higher status of Mihintale. The claim is not to be the original cradle of Sri Lanka’s Buddhism, that’s Mihintale. The legend only has it that Mahinda Thero made a sshort break on his flight to Mihintale. He landed in Isenbessagala, as he saw hermits who invited him to have a break. The legend stresses that Missionary Mahinda came here, for the first time touching the ground of Sri Lanka, without preaching to the locals who invited him. This is to say, that Buddhism was not introduced here but in Mihintale where, according to the chronicles, Mahinda Thero then held his first sermon, in presence of the king of Anuradhapura. There can be some truth in the legend of Isenbessagala, insofar hermits had already lived on the island orior to the arrival of Buddhism. For example Jain monks, known as Nigantha in the chroncles, seem to have lived in Anuradhapura even prior to Buddhism. Probably, Mahinda was not even the first Buddhist monk arriving in Sri Lanka. Some reclusive monks seem to have lived in the east of the island earlier on. However, this does not belittle the outstanding historic role of Missionary Mahinda, since those earlier Buddhists in the island only lived in a Buddhist way but without converting lay people on a large scale. The historical significance of Mahinda is that he was the Buddhist who converted the king of Anuradhapura, thereby bringing Buddhism to the people of an entire kingdom and in turn elevating the status of this kingdom. Buddhism served as a cultural starting point for Anuradhapura to become the predominant city of the island.

But to return to Issenbessagala, the stupa on the summit is said to indicate the spot where Mahinda landed and had a break on his way to Mihintale and touched Sri Lanka for the first time. The modern stupa is placed on a terrace surrounded by a wall with a frieze of dozens of elephants. Such an elephant frieze at stupa terrace walls is known as Hastiprakaras, which translates to “elephant wall”, Prakaras being the outer walls of temple compounds in Indian architecture. Such elephant friezes are also known from Sri Lanka’s most famous stupa, Ruwanweliseya in Anuradhapura and from many chedis in Southeast Asia.

Isenbessagala claims to have been the first landing place of Missionary Mahinda, who introduced Buddhism to the island nation of Sri Lanka. This local legend is not narrated in the ancient chronicles. Mihintale 27 km further south is the venerated as the place where Monk Mahinda arrived, the son of India’s Emperor Ashoka. The legend of Isenbesssagala does not dare to dispute this higher status of Mihintale. The claim is not to be the original cradle of Sri Lanka’s Buddhism, that’s Mihintale. The legend only has it that Mahinda Thero made a sshort break on his flight to Mihintale. He landed in Isenbessagala, as he saw hermits who invited him to have a break. The legend stresses that Missionary Mahinda came here, for the first time touching the ground of Sri Lanka, without preaching to the locals who invited him. This is to say, that Buddhism was not introduced here but in Mihintale where, according to the chronicles, Mahinda Thero then held his first sermon, in presence of the king of Anuradhapura. There can be some truth in the legend of Isenbessagala, insofar hermits had already lived on the island orior to the arrival of Buddhism. For example Jain monks, known as Nigantha in the chroncles, seem to have lived in Anuradhapura even prior to Buddhism. Probably, Mahinda was not even the first Buddhist monk arriving in Sri Lanka. Some reclusive monks seem to have lived in the east of the island earlier on. However, this does not belittle the outstanding historic role of Missionary Mahinda, since those earlier Buddhists in the island only lived in a Buddhist way but without converting lay people on a large scale. The historical significance of Mahinda is that he was the Buddhist who converted the king of Anuradhapura, thereby bringing Buddhism to the people of an entire kingdom and in turn elevating the status of this kingdom. Buddhism served as a cultural starting point for Anuradhapura to become the predominant city of the island.

But to return to Issenbessagala, the stupa on the summit is said to indicate the spot where Mahinda landed and had a break on his way to Mihintale and touched Sri Lanka for the first time. The modern stupa is placed on a terrace surrounded by a wall with a frieze of dozens of elephants. Such an elephant frieze at stupa terrace walls is known as Hastiprakaras, which translates to “elephant wall”, Prakaras being the outer walls of temple compounds in Indian architecture. Such elephant friezes are also known from Sri Lanka’s most famous stupa, Ruwanweliseya in Anuradhapura and from many chedis in Southeast Asia.

A hermit’s cave can be seen at the foot of the monadnock, near the modern temple. In the case of Isenbessagala, this cave is not just an overhanging rock but a tunnel-like room. Usually the door is closed, because the cave is still in use as a monk’s dwelling.

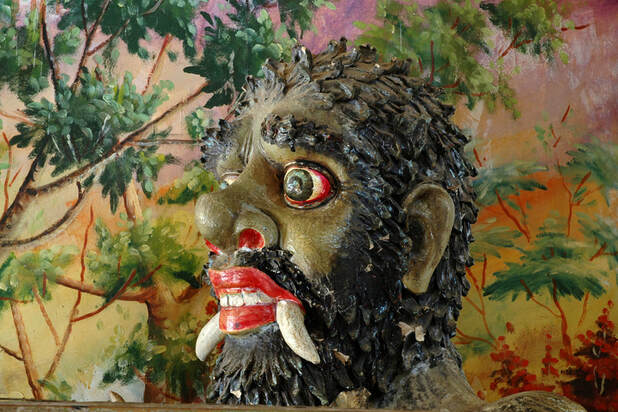

The monastery of Isenbessagala has a new image house crowded with extremely colourful depictions of heavenly beings. The door to the main shrine room is arched by a typical Makara Torana. Tendrils forming the arch connect the mouths of the Kirthimuka of the central apex and the Makara crocodile-dragons on either side. Above this dragon arch, deities can be seen, protecting the entrance. Indra, with his emblematic animal, the elephant Airava, and Vishnu with his peacock are Hindu gods also venerated in Buddhism, as protectors of the religion.

On the opposite wall, a demon can be seen, also protecting the temple, by deterring other evil beings from entering it. In particular, Bhairava threatens thieves who intend to steal treasures hidden by kings in the nearby rock of Isenbessagala. The demon succeeds in deterring them by his scary appearance. This local demon is called Bhairava. The name means horror. In Hinduism, Bhairava is known as the form of Shiva decapitating Brahma out of wrath, thereby reducing the number of Brahma’s heads from five to four. Shiva, though the supreme god in Tamil faith, is usually not venerated by Buddhists. In this case, the highest Hindu god is reduced to a demon and guardian.

The wide and flat jungle area surrounding the rock of Issenbassagala is known a Vanni, also spelt Wanni. In recent times, the term Vanni refers to those parts of the nearby Northern Province that are on the mainland Of Sri Lanka, without including Jaffna peninsula. Whereas Jaffna was under control of Sri Lanka’s government most of the time, it was in fact the Vanni area that was the core of the rebel-held territories during the civil war, with Kilinochchi being a kind of capital of the secessionists. The Vanni region was the last stronghold of the terrorist ans child-soldier recruiting army of the LTTE and the place of their final defeat in 2009, too.

Historically, the term Vanni does not refer to Tamil kingdoms but to principalities of people who formed a third ethnicity, similar to the Weddahs. During the Anuradhapura period, the Vanni principalities were under control of local chieftains. They became more influential after the breakdown of the Polonnaruwa kingdom due to the invasion of Kalinga Magha in the early 13h century. When the Cultural Triangle further south lost its status as the island’s main settlement area and the Sinhalese population centre shifted to the southwest, the Vanni area in between the Tamil kingdom of Jaffna and the Sinhalese kingdom further south became a kind of buffer zone, having closer trade relations with the Jaffna peninsula, though being almost independent, with alternating alliances. The Vanni region then was larger than today’s Northern Province. In the late Middle Ages, much of what is now Anuradhapura District belonged to Vanni chieftains, too. Only the northern Vanni chieftains were predominantly Tamil. Many of those Vanni dynasties of feufal chiefs were descendents of noblemen who had fled from Southern India due to Muslim invasions fromNorthern India. However, the language spoken by the population was strange Sinhalese dialect similar to that of the indiginous Weddah tribes. But in contrast to the Weddah creol, a mix of an original language and Sinhala, the language of the Vannis had a highly differentiated vocabulary and complex grammar, indicating that it was a relic of a very ancient culture.