Originally, so-called caves, which are actually rock overhangs, were used as living quarters by small communities of forest monks. Because the forest hermits were considered particularly holy, they attracted pilgrims. And for the needs of the pilgrims, some of the caves were soon converted into ceremonial buildings, so-called image houses, which were decorated with sculptures and paintings. Most of these painted cult caves seen in Sri Lanka date from the Kandyan period, if not the subsequent colonial period.

Historical background

Older cave monasteries, which had often been abandoned during the Kandy period, were revived and refurbished as part of a Buddhist renewal movement in the 18th century. Buddhism in Sri Lanka was in crisis in the 17th century. This decline is often attributed to the colonial rule of the Portuguese and then the Dutch, who more or less suppressed non-Christian religions. That's not wrong, but it's not enough of an explanation, because the Kandyan kingdom in the center of the island defined itself in terms of cultural differentiation from the foreign powers. The first real king of Kandy, Vimaladharmasurya I, had demonstratively converted back from Catholicism to Buddhism and, in particular, had instrumentalised the cult of Buddha's sacred tooth to legitimize his rule. One would actually expect that under such condition of dissociation from the colonial powers, Buddhism would have flourished in that part of the island that was not under Christian control. In fact, some Kandyan kings, especially Vimaladharmasurya II, not only tried to promote the tooth cult, but also to strengthen the order's lineage, namely through contacts with monks in Myanmar. But the ongoing crisis in the Buddhist monastic tradition was of its own making. The main root cause for the decline of religious discipline was the wealth of the monasteries in land ownership. It led to monasteries being viewed primarily as profitable businesses that enabled their operators, the monks, to live a profitable lifestyle. The monasteries often remained in the hands of the same families for generations. In order to keep the property within the family, nephews became the successors in the monastery management. (There were also illegitimate children of the monks, but they were not entitled to inherit.) The secular clergy not only lived in a secular manner - in prosperity and in marriage-like relationships - but also cared neither for Buddhist studies nor for maintaining the order's rules. In particular, there was a lack of the crucial, regular ordination. Formally, most of the clergy remained without higher ordination. For this reason, they were no longer actually regarded as monks, but were formally considered samaneras, young monks without full ordination. They were called Ganinnanses. The kings were more interested in the cult of the Sacred Tooth and priestly consecrationfor their self-legitimation than in a proper religious life of the Buddhist monastic tradition. Attempts to renew the ordination lines, as under Vimaladharmasurya II, remained isolated attempts without lasting effect.

However, around the turn to the 18th century, there was a reform movement from within the clergy, a systematic attempt to revive studies of ancient Buddhist texts and to gain a fully legitimate higher ordination from outside Sri Lanka. The most prominent of such efforts was Welivita Saranakara Samanera, who therefore even risked to alienate his relationship with the royal court. But the situation at the royal court changed in favour of the Buddhist reform movement, when a new dynasty, the Nayakkars from South India, not related by blood but by marriage, came to power, when the last Sinhalese king, Vira Narendra Sinha, died without male successor. The Nayakkars originally were Hindus. But ironically, their alien origin all the more motivated them to become patrons of the kingdom's traditional religion, Buddhism, as a means, full of symbolism, to undermine doubts concerning the legitimacy of their rule. Though the relationship between the royal court and the leadership of the monasrtic reform movement did not remain without strains and conflict, all in all the Nayakkar rulers did much more than their Sinhalese predecessor on the Kandyan throne to strengthen the commitments of monastic life to the canonical Buddhist rules. Most importantly, a new line of ordination was introduced from Siam. After two earlier attempts had failed due to shipwreck resp. the sudden death of the first Nayakkar king, Sri Vijaya Rajasinha, the renewed line of ordination was finally introduced from Siam in a large ordination ceremony on July 20, 1753, an Esala Poya day. The ordination line then established is known as Syam Nikaya and predominant in the interior of the island till the present day. However, the combination of internal reform movement and royal patronage did not only care about strengthening the monastic order. It also reestablished Pali studies of sacred texts and, last not least, led to systematic efforts of renovating several ancient cave monasteries that had been left by the clergy and fallen into decay in the previous decades. Dambulla and Ridivihara, to name only the most prominent examples, became new centers of monastic life and soon regained enourmous reputation that even continued under British rule in the next century. Severel dozens of cave temples were not only revived with monastic life but also refurbished with patronage from the royal court, as in the case of Dambulla, or local leading families. Most or the murals that can be seen in Sinhalese cave temples today, are from this period of renovation, though traves of paintings from earlier periods have survived at certain places, as a reminder, that the embellishment of the caves has a long tradition and had been a continous effort in previous centuries.

However, around the turn to the 18th century, there was a reform movement from within the clergy, a systematic attempt to revive studies of ancient Buddhist texts and to gain a fully legitimate higher ordination from outside Sri Lanka. The most prominent of such efforts was Welivita Saranakara Samanera, who therefore even risked to alienate his relationship with the royal court. But the situation at the royal court changed in favour of the Buddhist reform movement, when a new dynasty, the Nayakkars from South India, not related by blood but by marriage, came to power, when the last Sinhalese king, Vira Narendra Sinha, died without male successor. The Nayakkars originally were Hindus. But ironically, their alien origin all the more motivated them to become patrons of the kingdom's traditional religion, Buddhism, as a means, full of symbolism, to undermine doubts concerning the legitimacy of their rule. Though the relationship between the royal court and the leadership of the monasrtic reform movement did not remain without strains and conflict, all in all the Nayakkar rulers did much more than their Sinhalese predecessor on the Kandyan throne to strengthen the commitments of monastic life to the canonical Buddhist rules. Most importantly, a new line of ordination was introduced from Siam. After two earlier attempts had failed due to shipwreck resp. the sudden death of the first Nayakkar king, Sri Vijaya Rajasinha, the renewed line of ordination was finally introduced from Siam in a large ordination ceremony on July 20, 1753, an Esala Poya day. The ordination line then established is known as Syam Nikaya and predominant in the interior of the island till the present day. However, the combination of internal reform movement and royal patronage did not only care about strengthening the monastic order. It also reestablished Pali studies of sacred texts and, last not least, led to systematic efforts of renovating several ancient cave monasteries that had been left by the clergy and fallen into decay in the previous decades. Dambulla and Ridivihara, to name only the most prominent examples, became new centers of monastic life and soon regained enourmous reputation that even continued under British rule in the next century. Severel dozens of cave temples were not only revived with monastic life but also refurbished with patronage from the royal court, as in the case of Dambulla, or local leading families. Most or the murals that can be seen in Sinhalese cave temples today, are from this period of renovation, though traves of paintings from earlier periods have survived at certain places, as a reminder, that the embellishment of the caves has a long tradition and had been a continous effort in previous centuries.

Kandyan Paintings

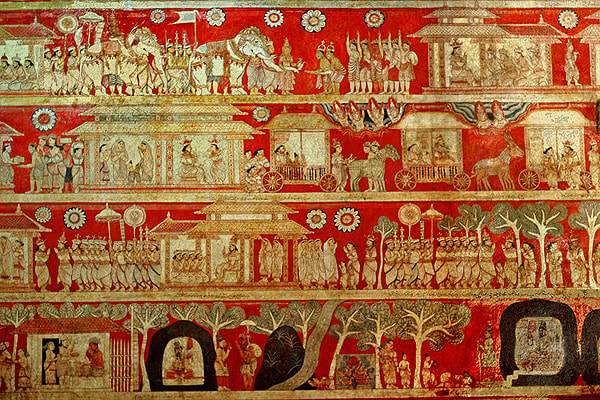

The rock surfaces of the cave ceilings as well as the exterior walls built by clay stuck in between sticks where plastered with a white colored clay, on which the new images in the specific Kandyan style were painted. The Kandyan murals are unsually arranged in horizontal rows. Most of them illustrate Jataka stories in continuos bands, tales of exemplary moral deeds of the Buddha in his previous lives, when he often committed self-sacrifice for the benefit of others. They are narrated in bands stretching over several rows. The distinct scenes of a tale are separated from each other by trees or buildings. Today, the clothing of the depicted persons and the style of the painted palaces are highly important visual sources reflecting the Kandyan culture of the 18th century. The background of the frescoes were painted in a red color, the blanks are filled with highly stylized lotus flowers, particularly the ceilings are often entirely covered by geoamtrically arranged patterns of flowers. The paints used in Kandyan frescoes are a combination of mineral and organic materials, the use of materials from trees and fruits contrasts with Anuradhapura-period paintings for which only minerals had been used. The predominant colurs are yellow and red and white and green. Blue can rarely be seen, except from places such as Mulkirigala near the coast, where colours could be imported. The painters belonged to specialised families or castes that often decorated several temples. But there were different groups of painters in different regions. Some individual artists are also known by name.

Apart from the Jataka stories, other themes occur in a repetitive way in different Kandyan temples, such as episodes from the early palace life of Shakyamuni, before he became a Buddha, the moment of his enlightenment when he remained undistrwcted despite being attacked by demons, his first preaching, rows of his disciples, and also the previous Buddhas, each seated under a specific tree and accompanied by a small person that represents the later Shakyamuni, who in his previous lives venerated or helped the earlier Buddhas and was recognized by them as a later Buddha himself. Another recurring subject is the visit of the Buddha in the Thushita heaven. Apart from such general Buddhist scenes, there are also specific Sri Lankan themes, most importantly the 16 Buddha-visited sites of the island, the so-called Solosmasthana. Most of them are stupas, again arranged in several lines, but one of them is a mountain (Siri Pada) and one a highly stylised rock with a hole rpresenting a cave (Diva Guhawa). In some cases, most importantly in Dambulla, also scenes from the history of Sri Lanka are depicted.

Apart from the Jataka stories, other themes occur in a repetitive way in different Kandyan temples, such as episodes from the early palace life of Shakyamuni, before he became a Buddha, the moment of his enlightenment when he remained undistrwcted despite being attacked by demons, his first preaching, rows of his disciples, and also the previous Buddhas, each seated under a specific tree and accompanied by a small person that represents the later Shakyamuni, who in his previous lives venerated or helped the earlier Buddhas and was recognized by them as a later Buddha himself. Another recurring subject is the visit of the Buddha in the Thushita heaven. Apart from such general Buddhist scenes, there are also specific Sri Lankan themes, most importantly the 16 Buddha-visited sites of the island, the so-called Solosmasthana. Most of them are stupas, again arranged in several lines, but one of them is a mountain (Siri Pada) and one a highly stylised rock with a hole rpresenting a cave (Diva Guhawa). In some cases, most importantly in Dambulla, also scenes from the history of Sri Lanka are depicted.

for opening a destination page in a new tab, please click the image

for going to the destination page in the same tab, please click the name in the text line below the image

for going to the destination page in the same tab, please click the name in the text line below the image