The small Degaldoruwa cave temple east of Kandy is famous for its Kandy paintings from the late 18th century, excellent representations of Jataka episodes in particular. Less known among tourists, the serene Degaldoruwa is well worth a visit for those travellers interested in Sri Lanka’s cultural heritage.

Content of our Degaldoruwa page:

Location - Intro - History - Kandy Paintings - Interior Rooms - Cave Shrine - Jataka Murals

Location - Intro - History - Kandy Paintings - Interior Rooms - Cave Shrine - Jataka Murals

Location

The monastery and cave temple of Degaldoruwa, now part of a new monastic complex, is pretty easily accessible, located just 7 km (4 miles) east of the center of Kandy, on the other side of the Mahaweli River. Despite its close proximity to Kandy, this is a temple is rarely visited by tourists and remains a hidden treasure.

|

Introduction: Degaldoruwa Raja Maha Viharaya & its significance

Degaldoruwa (emphasis on the "o") and Dambulla provide the most well-known examples of 18th-century Kandy paintings. Degaldoruwa is sometimes referred to as the "second Dambulla." However, this name is misleading. Degaldoruwa has only one cave with paintings, and its statues are not as impressive as those in Dambulla. Other rock temples like Ridivihara in Kurunegala or Mulkirigala in the south bear a stronger resemblance to Dambulla in terms of overall pattern. What sets Degaldoruwa apart are only its highly detailed Kandy paintings. In this aspect, Degaldoruwa stands up well to comparison with Dambulla. In fact, the Jataka scenes in Degaldoruwa are more vibrant, with more dynamic and action-packed groups of figures than most of the much more famous murals in Dambulla. Therefore, for the study of this typical subject of Kandy painting, there is hardly a better place in Sri Lanka than Degaldoruwa.

The present-day Degaldoruwa monastery, outside the fresco cave, has a new building for the monks' accommodations and assemblies. It is a shaded combined stone and wood construction around an atrium-like courtyard, reminiscent of what was formerly reserved for the highland nobility in their residences. This actual monastery cannot be visited. It also serves the function of a village monastery for the surrounding residents, for example, providing classes of a Buddhist Sunday school (photo).

History of Degaldoruwa

The Degaldoruwa temple, in its current form, was commissioned by the famous Kandy king, Kirthi Sri Rajasingha (1747-1782), but it was only completed under his brother and successor, Rajadhi Rajasingha (1782-98). Kirthi Sri Rajasingha was a great restorer of the Buddhist order. He revitalized numerous abandoned historical monasteries, resettling them with monks and adorning the places of worship with magnificent new paintings. Some temples of this restoration period, like Degaldoruwa, can be considered outright new foundations. Temples enjoying royal patronage through land grants or payment to artists are called "royal monastic complexes," which is the meaning of "Rajamahavihara" ("Raja Maha Viharaya").

The typical Kandy style in painting is actually a result of King Kirthi Sri Rajasingha's sponsorship. Most of the best examples of Kandy paintings in Sri Lanka date from his time. However, the king passed away before the completion of the Degaldoruwa temple. His successor, Rajadhi Rajasingha, finally handed over the then completed temple to the monk Moratota Dhammarakkhita Nayaka Thera, who had once been his teacher and was regarded as a great scholar.

The typical Kandy style in painting is actually a result of King Kirthi Sri Rajasingha's sponsorship. Most of the best examples of Kandy paintings in Sri Lanka date from his time. However, the king passed away before the completion of the Degaldoruwa temple. His successor, Rajadhi Rajasingha, finally handed over the then completed temple to the monk Moratota Dhammarakkhita Nayaka Thera, who had once been his teacher and was regarded as a great scholar.

for more background information on the history of Degaldoruwa click here...

The dedication inscription of the Degaldoruwa temple by King Rajadhi Rajasingha is preserved on copper plates. It mentions all the parts of the building donated by the two kings, including the statues in the interior, the tree planted in the vicinity, and the provision of ritual objects. It explicitly states, "And His Majesty also provided the artists, the painters, and sculptors with valuable clothing and money." The dates 1771 for the consecration ceremony and 1786 for the land grants indicate that Rajadhi Rajasingha was involved in the planning of the Degaldoruwa temple even before ascending the throne and that the lands were gifted to the monastery only after its completion. This confirms that both the construction and artistic embellishment were directly financed by the royal house.

The intensification of tempera painting during the era of Kirthi Sri Rajasingha is not a coincidence. It is related to the king's concerted efforts to restore the Buddhist religion. Alongside the colourful decoration of abandoned or newly founded monastery temples, this revival of the indigenous religion also included expanding the processions of Hindu temples in Kandy into a joint procession at the peak of which not only were the Hindu deities carried through the city, as had been done until then, but also, as in the middle Anuradhapura period over a thousand years earlier, the Buddhist royal relic, the Sacred Tooth. The famous Kandy Perahera, now one of the most magnificent religious processions in Asia, is, in fact, an innovation introduced by King Kirthi Sri Rajasingha as a Buddhist celebration, though Tooth Pageants had already taken place in a distant past. However, the king’s main achievement was his contribution to the reform of the monastic order. For this purpose, he supported the monk Saranankara in introducing an ordination line from Siam and creating a code of conduct for monkhood, aiming to spiritually renew the monastic community, which had become quite worldly as a landowning aristocracy. The temple endowments, including funding for painters, should be seen in connection with this monastic reform. The king's heightened interest in strengthening Buddhism may have been influenced by the Christian competition from European colonial powers in the lowlands, but it could also have been motivated by Kirthi Sri Rajasingha's biographical background. He belonged to a minor branch of the Sinhalese royal house and was actually of South Indian Tamil origin. He was originally Hindu. Promoting Buddhism, the religion of the majority, may have served as a legitimation of his rule, which otherwise could have been perceived as foreign rule by a Tamil or as privileging the Hindu minority.

The intensification of tempera painting during the era of Kirthi Sri Rajasingha is not a coincidence. It is related to the king's concerted efforts to restore the Buddhist religion. Alongside the colourful decoration of abandoned or newly founded monastery temples, this revival of the indigenous religion also included expanding the processions of Hindu temples in Kandy into a joint procession at the peak of which not only were the Hindu deities carried through the city, as had been done until then, but also, as in the middle Anuradhapura period over a thousand years earlier, the Buddhist royal relic, the Sacred Tooth. The famous Kandy Perahera, now one of the most magnificent religious processions in Asia, is, in fact, an innovation introduced by King Kirthi Sri Rajasingha as a Buddhist celebration, though Tooth Pageants had already taken place in a distant past. However, the king’s main achievement was his contribution to the reform of the monastic order. For this purpose, he supported the monk Saranankara in introducing an ordination line from Siam and creating a code of conduct for monkhood, aiming to spiritually renew the monastic community, which had become quite worldly as a landowning aristocracy. The temple endowments, including funding for painters, should be seen in connection with this monastic reform. The king's heightened interest in strengthening Buddhism may have been influenced by the Christian competition from European colonial powers in the lowlands, but it could also have been motivated by Kirthi Sri Rajasingha's biographical background. He belonged to a minor branch of the Sinhalese royal house and was actually of South Indian Tamil origin. He was originally Hindu. Promoting Buddhism, the religion of the majority, may have served as a legitimation of his rule, which otherwise could have been perceived as foreign rule by a Tamil or as privileging the Hindu minority.

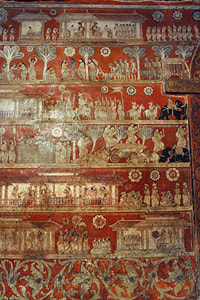

Kandy Paintings alias Sittara Murals

The main attraction of Degaldoruwa are typical wall and cave paintings from the 18th century. Such Sittara murals, also known as Kandy paintings or Kandyan period frescoes, often replaced images from previous periods that had faded away in the course of the centuries. Inspired by temple murals of Hindu temples and palaces in South India from previous centuries, Kandy paintings, though less complex, can illustrate entire narratives, namely canonical Jataka tales. They do so in horizontal rows, dividing the plastered and whitened surfaces, and the scene in one row are divided from each other by trees or petals or buildings, or rivers. The storyline is represented i a zig-zag pattern. The pictures of people usually show faces and legs from the side. The background of the frescoes were painted in a red or white colour, with additional flowers fillings the blanks. The technique of Kandyan murals is tempera, painting on dry plaster, whereas the more than a millenium older Sigiriya paintings were genuine frescos. The pigments and also the bonding material for the paintings and even the paintbrush were from the nature. In contrast to the Sigiriya frescoes, not only minerals were used, but also organic colours. In particular, Ixora was used for the intensifying of the red colours. Blue pigments, which are rare, were made from Indigofera, or ready-made Indigo was imported from India in some cases, though not in the highlands.

for more information about Kandy paintings click here...

Named painters created the murals of Degaldoruwa. Devendra Mulachari was considered the lead artist. One of his colleagues is mentioned as Nilagama Patabendi. His name indicates his origin from the village of Nilagama in the central Matale district, known as the birthplace of the "Sittaras," as the temple painters were called in Sinhalese, even before the Kandy period. The most famous master working in Degaldoruwa was Silvattenne Unnanse. The name under which he is known is more of a title than a personal name. "Silvat Unnanse" means that he was trained as a novice but did not receive the full monk ordination called "Uposatha“ or "Uposampada." Therefore, he does not carry the suffix "Thera." His personal name was actually Devaragampola.

Most often, painters were not the monks of a monastery themselves, as the canonical monastic rule prohibited monks from engaging in painting, considered a craft in South Asia. Only in the Kandy period do we find monks among the named artists occasionally. It might well be that such monks only supervised the painters. Or a monk’s own painting activity was probably considered in line with monastic rules, as long as the painting monk did not engage in earning money, and as long as the decorations served not for the pleasure of the monks but for the religious instruction and edification of the lay followers who came as visitors.

In India, for centuries, specific castes traditionally created temple decorations. In Sri Lanka, small groups of so-called "Sittaras" worked as professional painters, traveling from place to place to adorn temples. From the time of Kirthi Sri Rajasingha, when most highland temples received their paintings, such guilds of painters and their masters are partially known by name. It is likely that in the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa periods in earlier centuries, the organizational form for embellishing sacred buildings was a guild system, similar to medieval Europe or India. The groups led by a master could be family associations or come from the same village, such as the mentioned Nilagama ("Blue Village"), and perhaps some decorators came from southern India, Kerala, the home region of King Kirthi Sri Rajasingha, where stylistic models for Kandy painting can be found.

The painting schools were called "Gurukulas" because a teacher, a "Guru" as a master of the guild, trained the successive generations. Each Gurukula - not the individual artist - had its own stylistic signature. In some places, such as Degaldoruwa, they worked side by side, so one could see different traditions and techniques in the same location. In Degaldoruwa, the ceiling paintings with large monsters differ significantly from the miniature Jataka paintings on the brick walls of the cave chamber. Similar differences can be found elsewhere. This is because a location was not outfitted in a specific style by a single painter but the Gurukulas with their consistent motifs and techniques moved from place to place, deploying several at one location, as in Degaldoruwa.

According to UNESCO estimates, there are over 1,000 temples in Sri Lanka with paintings more than a hundred years old, with about 300 dating back to the era of Kirthi Sri Rajasingha in the 18th century, featuring the highest-quality Kandy paintings. However, not many groups of "Sittaras" were active in Sri Lanka during the time of Kirthi Sri Rajasingha. Only the temples in the vicinity of Kandy exhibit the classical style of Kandy painting. Temples in the south developed their own style, more colourful, sculptural, and rich in motifs, so it's unlikely that the organized Sittaras from the Highlands were involved. Many of the painted temples of that time are located in the Uva province in the southeast of the highlands. The Kandy paintings there are much simpler and less sophisticated than those in the Kandy region. The murals in Uva were probably created not by semi-professional Sittaras but by local craftsmen who were not trained or experienced painters. There might even have been rice farmers among the decorators of the Uva temples. In general, even the Sittaras organized in Gurukulas did not live solely from painting but engaged in various crafts. They were goldsmiths, ivory carvers, wood engravers, bronze casters, and painters at the same time. (By the way, the original profession of most universal artists of the Italian Renaissance was that of a goldsmith.)

Most often, painters were not the monks of a monastery themselves, as the canonical monastic rule prohibited monks from engaging in painting, considered a craft in South Asia. Only in the Kandy period do we find monks among the named artists occasionally. It might well be that such monks only supervised the painters. Or a monk’s own painting activity was probably considered in line with monastic rules, as long as the painting monk did not engage in earning money, and as long as the decorations served not for the pleasure of the monks but for the religious instruction and edification of the lay followers who came as visitors.

In India, for centuries, specific castes traditionally created temple decorations. In Sri Lanka, small groups of so-called "Sittaras" worked as professional painters, traveling from place to place to adorn temples. From the time of Kirthi Sri Rajasingha, when most highland temples received their paintings, such guilds of painters and their masters are partially known by name. It is likely that in the Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa periods in earlier centuries, the organizational form for embellishing sacred buildings was a guild system, similar to medieval Europe or India. The groups led by a master could be family associations or come from the same village, such as the mentioned Nilagama ("Blue Village"), and perhaps some decorators came from southern India, Kerala, the home region of King Kirthi Sri Rajasingha, where stylistic models for Kandy painting can be found.

The painting schools were called "Gurukulas" because a teacher, a "Guru" as a master of the guild, trained the successive generations. Each Gurukula - not the individual artist - had its own stylistic signature. In some places, such as Degaldoruwa, they worked side by side, so one could see different traditions and techniques in the same location. In Degaldoruwa, the ceiling paintings with large monsters differ significantly from the miniature Jataka paintings on the brick walls of the cave chamber. Similar differences can be found elsewhere. This is because a location was not outfitted in a specific style by a single painter but the Gurukulas with their consistent motifs and techniques moved from place to place, deploying several at one location, as in Degaldoruwa.

According to UNESCO estimates, there are over 1,000 temples in Sri Lanka with paintings more than a hundred years old, with about 300 dating back to the era of Kirthi Sri Rajasingha in the 18th century, featuring the highest-quality Kandy paintings. However, not many groups of "Sittaras" were active in Sri Lanka during the time of Kirthi Sri Rajasingha. Only the temples in the vicinity of Kandy exhibit the classical style of Kandy painting. Temples in the south developed their own style, more colourful, sculptural, and rich in motifs, so it's unlikely that the organized Sittaras from the Highlands were involved. Many of the painted temples of that time are located in the Uva province in the southeast of the highlands. The Kandy paintings there are much simpler and less sophisticated than those in the Kandy region. The murals in Uva were probably created not by semi-professional Sittaras but by local craftsmen who were not trained or experienced painters. There might even have been rice farmers among the decorators of the Uva temples. In general, even the Sittaras organized in Gurukulas did not live solely from painting but engaged in various crafts. They were goldsmiths, ivory carvers, wood engravers, bronze casters, and painters at the same time. (By the way, the original profession of most universal artists of the Italian Renaissance was that of a goldsmith.)

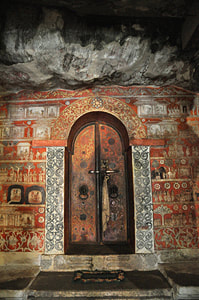

The rooms of the ancient Degaldoruwa Temple

The painted place of worship, opened by the monks to visitors for a suitable donation, is located in a niche under a 15-meter-high, very flat-looking rock (photo). At its top, there is an old Bo tree and a stupa. In front of the cave niche, a white-washed brick-made porch with a wooden roof has been built, mentioned in the foundation inscription of Rajadhi Rajasingha as a royal commission.

This porch is divided into two parts. The front part is called Digge, serving as a storage place for ritual items, such as drums for processions. The Digge has some old wooden pillars as roof supports. Unusually, the Digge is not spatially separated from the shrine. Normally, a Digge stands as a separate wooden structure clearly apart from the image houses or even elsewhere in the monastery compound. Here in Degaldoruwa, it forms a kind of initial transverse porch, from which one enters the second and larger anteroom in front of the cave through a door with a Makara Torana (photo). Its roof is supported by stone columns.

Most Kandyan cave temples have such vestibules, but they are usually narrower and simpler than here. In Degaldoruwa, this vestibule itself is the largest room and splendidly adorned with very different types of Kandy paintings. Above the striking main motif (the Jataka scenes on the rear wall that separates the vestibule from the worship cave) you can see large flower motifs under the ceiling, which is partly formed by the protruding rock (photo). Other decorative forms, namely delicate foliage, adorn the pillars. The arch constructions are reminiscent of European models known from contemporary colonial buildings.

As mentioned, the main place of worship of the rock temple is located, like so often in Sri Lanka, under a natural overhanging rock. This inner cave room is separated from the aforementioned vestibule by a mud-brick wall. At the foot of the main entrance from the anteroom into this image cave lies a typical Kandy moonstone (photo) with its triangular appearance. The pilasters next to the gate still have metallic settings, where semi-precious stones were once embedded.

The cave shrine and its murals

*Photo 9.4.05 - 06 Degaldoruwa sleeping Buddha**

The plastic ornamentation of the actual cave image house consists of a large reclining Buddha (photo) and several smaller seated Buddha figures, as mentioned in the copper foundation tablet of Rajadhi Rajasingha. A cobra is said to live in alcoves of the cave, the serpent has been spotted near the Buddha statues. Near the temple, there is also said to be a deep tunnel.

The plastic ornamentation of the actual cave image house consists of a large reclining Buddha (photo) and several smaller seated Buddha figures, as mentioned in the copper foundation tablet of Rajadhi Rajasingha. A cobra is said to live in alcoves of the cave, the serpent has been spotted near the Buddha statues. Near the temple, there is also said to be a deep tunnel.

Both on the outside and inside of the dividing wall between the vestibule and the cave space, there are illustrations of Jataka scenes in the classical Kandy style. Additional outstanding tempera paintings from the Kandy period can be seen under the cave ceiling. Here, in the middle - as in Dambulla - one can see the Buddha in Bhumisparsha Mudra, at the moment of his enlightenment (photo).

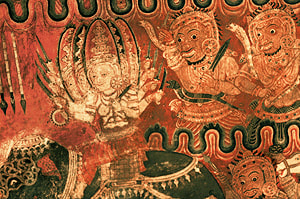

He is surrounded by demons trying to distract him (photo). This popular motif, known as "Mara Yuddha" or "Mara Yuddhaya," means "Battle with Mara."

It signifies that the evil demon king Mara fought against someone being about to attain Buddhahood because, as the Lord of Death, he wanted to prevent anyone from finding a way out of the cycle of life and death and thus escaping his power. Therefore, he sends his demon troops to attack the meditating Siddhatta Gotama (Siddharta Gautama) to prevent him from becoming a Buddha. Mara leads the demon army like a general from his war elephant (photo) into battle against the imminent overcoming of suffering and death that Siddhatta is about to achieve.

The depictions of the demons of the army (photo), rushing against the emerging Buddhahood, symbolize Siddhattas internal struggles to overcome this world of suffering, These depiction of the attacks of the army of Mara are likely the most impressive of their kind in Sri Lanka, alongside those of Dambulla, of course. Almost every figure is differentiated in colour, facial expression, gesture, or clothing from the others.

The malevolent demons are always recognizable by their tusks as canines. And they have beards. However, one, the second behind Mara's elephant, has the head of a horse (photo).

Noteworthy are two demons to the right of the Buddha, carrying a musket (photo). Even the demon armies of the Buddhist world system do not shy away from technological progress, just like the Sinhalese soldiers who not only adopted but even improved the rifle technology of Europeans in the Kandy period.

The mural at the ceiling of the cave is framed by foliage. The large figures depicted on the walls are Arahants, disciples of Buddha who also attained enlightenment. Arahant are recognizable by the halos and lotuses.

The mural at the ceiling of the cave is framed by foliage. The large figures depicted on the walls are Arahants, disciples of Buddha who also attained enlightenment. Arahant are recognizable by the halos and lotuses.

The wall opposite the reclining Buddha shows scenes from the Jataka stories of the Buddha's past lives (photo) as well as images of stupas at important pilgrimage sites in Sri Lanka, these so-called Solosmasthanas are a typical theme of Kandyan paintings, too.

The depicted individuals are represented in different colours according to their rank. Those of higher status have lighter yellow tones, elephant handlers are in brown, servants sometimes in reddish hues, and laborers in dark brown. Trees and leaves are rendered in shades of gray due to a lack of green pigments. The depictions of rocks are almost black. Caves are strongly stylized, marked by bright areas entirely surrounded by a dark band representing the rocks (photo). The rare colour blue symbolizes water or clouds.

The famous Degaldoruwa Jataka Paintings in the Kandyan style

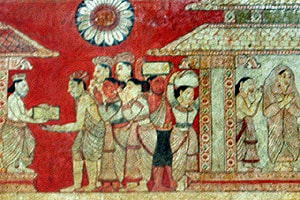

The paintings of Degaldoruwa are known for their extraordinary level of detail and the expressiveness of the faces. The Jataka illustrations on the outer wall leading to the inner cave are attributed to the mentioned renowned Sittara artist Devaragampola Silvattena (photo).

Despite the naive simplicity of his Kandy painting, he successfully captures the inner dynamics of an action, both in the facial expressions of individual figures and in the composition of the group of figures. In the chosen example, Prince Vessantara presents gifts (photo). As a virtuous giver, he exudes great dignity in the Buddhist sense, appearing almost indifferent rather than generously affectionate. Some of the waiting and receiving figures, especially women, display greedy expressions. Those returning after receiving royal gifts show great satisfaction. The recipients of the gifts are compositionally divided into two groups: those who are yet to receive gifts and those who have already been gifted. They move backward, with an unusually blue garment adding an additional colour contrast between the two groups.

Similar to European altar paintings from the Middle Ages, stories from the ancient scriptures are illustrated by figures that appear to be from the contemporary environment. Clothing and buildings, along with furnishings, in the Kandy paintings reflect those of the 18th century (photo). Insignias of royal dignity in the Kandyan highlands, as well as uniforms of servants or the simpler clothing of the rural population, are all fashioned in the genuine style of the 18th century. The manner of greetings and expressions of respect also provide information about the customs of this late Kandy period.

Even thematically, the historical background of the artists influences the portrayal of the Jataka stories. A striking example is the depiction of a procession with two white elephants (photo), though the depicted Jataka episode actually is about a single elephant. In the corresponding scene from the Vessantara Jataka, this scene marks the beginning of series of astoundingly generous gifts of Prince Vessantara, which will have devastating consequences for him.

The white elephant of Crown Prince Vessantara is considered a rain-bringer. When a drought broke out in a neighboring kingdom that the king there could not end despite a long rain ceremony, his advisers suggested bringing in the rain-bringing royal elephant of Vessantara. The king sent his Brahmins, who smeared themselves with ash like ascetics and marched to the capital Jetuttara, where Vessantara's father was the king. They waited at the city gates for Prince Vessantara riding out on his magnificent white elephant. When they saw him coming, they asked for a donation. When the king's son asked what donation they desired, they asked for the white elephant. Vessantara gave them his royal elephant, along with all the immeasurably precious jewelry he wore, and also the 500 families responsible for caring for the elephant. The earth trembled at the generosity of this pious gift from the future Buddha. However, the Brahmins immediately mounted the elephant and arrogantly rode into the middle of the city. And when the horrified population asked what they were doing on the king's elephant, they boasted of Vessantara's gift and mocked the people of Jetuttara with obscene gestures. The enraged population therefore ran to the king's palace and demanded the punishment of Vessantara for giving away the symbol of royal dignity. Fearing for his son's life, the king eventually succumbed to the pressure of the population and banished Vessantara from the city, which he had to leave the next day with his wife and children. Vessantara accepts this banishment voluntarily.

This famous episode in the Vessantara Jataka vividly recounts the adornment of the white royal elephant with jewel-encrusted cloths and accompanying honor umbrellas. The Kandy painters took this as an opportunity to represent the magnificent attire of the elephant in their depiction. However, they did so by depicting the decorative forms of the elephants in the festive processions of their time. And so they present Vessantara's famous gift in the form of a Kandy Perahera. As said above, the character of an elephant procession is further enhanced by the fact that two white elephants are seen one after the other, while in the Jataka story there is only mention of a single white royal elephant of the king's son. But the intended impression, that of a pageant, is deceiving at the same time. Actually, it’s the same elephant depicted twice, only in two consecutive scenes. On the left, the prince rides on the elephant, accompanied by a large entourage, but on the right, he stands in front of the elephant, reaching for its trunk to present it as a gift. Dismounted, he appears less majestic, a perception heightened by the absence of the umbrella and flag bearers.

The white elephant of Crown Prince Vessantara is considered a rain-bringer. When a drought broke out in a neighboring kingdom that the king there could not end despite a long rain ceremony, his advisers suggested bringing in the rain-bringing royal elephant of Vessantara. The king sent his Brahmins, who smeared themselves with ash like ascetics and marched to the capital Jetuttara, where Vessantara's father was the king. They waited at the city gates for Prince Vessantara riding out on his magnificent white elephant. When they saw him coming, they asked for a donation. When the king's son asked what donation they desired, they asked for the white elephant. Vessantara gave them his royal elephant, along with all the immeasurably precious jewelry he wore, and also the 500 families responsible for caring for the elephant. The earth trembled at the generosity of this pious gift from the future Buddha. However, the Brahmins immediately mounted the elephant and arrogantly rode into the middle of the city. And when the horrified population asked what they were doing on the king's elephant, they boasted of Vessantara's gift and mocked the people of Jetuttara with obscene gestures. The enraged population therefore ran to the king's palace and demanded the punishment of Vessantara for giving away the symbol of royal dignity. Fearing for his son's life, the king eventually succumbed to the pressure of the population and banished Vessantara from the city, which he had to leave the next day with his wife and children. Vessantara accepts this banishment voluntarily.

This famous episode in the Vessantara Jataka vividly recounts the adornment of the white royal elephant with jewel-encrusted cloths and accompanying honor umbrellas. The Kandy painters took this as an opportunity to represent the magnificent attire of the elephant in their depiction. However, they did so by depicting the decorative forms of the elephants in the festive processions of their time. And so they present Vessantara's famous gift in the form of a Kandy Perahera. As said above, the character of an elephant procession is further enhanced by the fact that two white elephants are seen one after the other, while in the Jataka story there is only mention of a single white royal elephant of the king's son. But the intended impression, that of a pageant, is deceiving at the same time. Actually, it’s the same elephant depicted twice, only in two consecutive scenes. On the left, the prince rides on the elephant, accompanied by a large entourage, but on the right, he stands in front of the elephant, reaching for its trunk to present it as a gift. Dismounted, he appears less majestic, a perception heightened by the absence of the umbrella and flag bearers.

In the line below, we see Vessantara bidding farewell, leaving his palace and riding into the forest in a horse-drawn carriage (photo). He had given away all his possessions to the city's residents. But four Brahmins had come too late to get a share of it. When they learned that Vessantara had already left, they asked the people if he had taken anything with him. They came to know that he had only moved away with the carriage. The Brahmins hurried after him and asked him to give them the four horses of the team. The future Buddha then indeed gave the horses to them. After that, four divine sons in the form of gazelles came and took the yoke of the wagon to pull it further. But soon another Brahmin crossed their path and asked for the carriage. Vessantara had his wife and children get out and also gave away the coach. The four divine sons then disappeared. In the corresponding illustration in Degaldoruwa, you can see the gods watching in the clouds as Vessantara makes gifts to the greedy Brahmins.

A punchline of the Vessantara stories is that the beneficiaries of the oversized gifts are never those in need but rather entirely unworthy of any attention. Vessantara even gives away his children to an old Brahmin named Jujaka, who only wanted them to do the work of his young wife. She had been teased for caring for her old husband and did not want to continue fetching water and serving him. She threatened to leave him, unless other slaves took over these tasks. She suggested asking Vessantara in the forest, as he was known for giving everything away, to have his children do the household chores. And so it happened. However, the old Brahmin treated Vessantara's children so poorly (photo) and beat them that they attempted to escape several times. But Vessantara suppressed any desire for revenge.

At the climax of the story, Vessantara even gives away his wife Madri Devi to an old man who desires her as a slave. But Vessantara immediately gets her back because it was the god Sakka who had asked him for the woman, but only to test Vessantara's willingness to sacrifice, one of the qualities that a Bodhisattva must possess in perfection. In the end, Vessantara is visited in the forest by his father with a large following to bring him home, where he is reunited with his children.

In addition to the Vessantara Jataka, the Sattubhatta Jataka is also depicted in Degaldoruwa, the story of the cake knapsack. This Jataka is considered an expression of the perfection of one of the 10 qualities of a Bodhisattva, namely perfect wisdom. It is expressed in a figurative manner. The future Buddha proves himself in this Jataka as clairvoyant. An old Brahmin with a cake knapsack, given to him by his wife, comes to a gathering where a wise man named Senaka preaches, who happens to be the future Buddha in this specific Jataka tale. The old Brahmin is full of sorrow because the gods had prophesied to him that he or his wife would die today. But the wise Bodhisattva Senaka sees through the entire background of the story and recognizes the following connection:

The young woman had once been given to the old Brahmin by other Brahmins because theay had embezzled and lost the donation funds that the old Brahmin had collected and entrusted to them. In compensation, they handed over their daughter to him. However, she had a lover and sent her husband away to collect new donations. In doing so, she gave him a bag with a cake as provisions, but unnoticed by the old Brahmin, a snake slipped into this bag. Now, imminent death threatens the old man due to this poisonous serpent. However, the snake becomes instantly harmless as the Bodhisattva recognizes the whole situation.

Out of gratitude, the old Brahmin wants to leave his collected donations to the Bodhisattva. But the future Buddha refuses and gives him additional funds. However, all the money is stolen by the woman and her lover. When the old Brahmin complains to the wise Bodhisattva, he tells him a trick to find out the lover: The old Brahmin should have his wife invite a group of guests every day, gradually decreasing in size. The one she always invites should be brought to him. So, this young man came, initially denying the theft in front of the Bodhisattva but finally confessing remorsefully when he recognizes him as the all-knowing Senaka. Then, the adulterers were punished, and the deceived man, who did not divorce his wife, was rewarded.

At the climax of the story, Vessantara even gives away his wife Madri Devi to an old man who desires her as a slave. But Vessantara immediately gets her back because it was the god Sakka who had asked him for the woman, but only to test Vessantara's willingness to sacrifice, one of the qualities that a Bodhisattva must possess in perfection. In the end, Vessantara is visited in the forest by his father with a large following to bring him home, where he is reunited with his children.

In addition to the Vessantara Jataka, the Sattubhatta Jataka is also depicted in Degaldoruwa, the story of the cake knapsack. This Jataka is considered an expression of the perfection of one of the 10 qualities of a Bodhisattva, namely perfect wisdom. It is expressed in a figurative manner. The future Buddha proves himself in this Jataka as clairvoyant. An old Brahmin with a cake knapsack, given to him by his wife, comes to a gathering where a wise man named Senaka preaches, who happens to be the future Buddha in this specific Jataka tale. The old Brahmin is full of sorrow because the gods had prophesied to him that he or his wife would die today. But the wise Bodhisattva Senaka sees through the entire background of the story and recognizes the following connection:

The young woman had once been given to the old Brahmin by other Brahmins because theay had embezzled and lost the donation funds that the old Brahmin had collected and entrusted to them. In compensation, they handed over their daughter to him. However, she had a lover and sent her husband away to collect new donations. In doing so, she gave him a bag with a cake as provisions, but unnoticed by the old Brahmin, a snake slipped into this bag. Now, imminent death threatens the old man due to this poisonous serpent. However, the snake becomes instantly harmless as the Bodhisattva recognizes the whole situation.

Out of gratitude, the old Brahmin wants to leave his collected donations to the Bodhisattva. But the future Buddha refuses and gives him additional funds. However, all the money is stolen by the woman and her lover. When the old Brahmin complains to the wise Bodhisattva, he tells him a trick to find out the lover: The old Brahmin should have his wife invite a group of guests every day, gradually decreasing in size. The one she always invites should be brought to him. So, this young man came, initially denying the theft in front of the Bodhisattva but finally confessing remorsefully when he recognizes him as the all-knowing Senaka. Then, the adulterers were punished, and the deceived man, who did not divorce his wife, was rewarded.

Two more Jatakas are illustrated in Degaldoruwa to the right of the main portal into the inner cave and to the left and right of a side door (photo). One of them is the Mahasilava-Jataka. It tells of the betrayal of a minister that almost costs the king and his loyal followers their lives because they are buried up to their necks in the field, but the king saves them all through various miraculous feats.

In the above image (photo), it is depicted how the righteous king presents generous donations that the recipients carry away on their heads. The back row of those waiting for the gifts consists of prisoners, as evidenced by their handcuffs.

The Sutasoma-Jataka is about a king who renounces his kingship in favor of forest solitude, after which his subjects follow him into asceticism. The cruel scene where literally people come under the wheels (photo) depicts an episode in which a man-eater drags King Sutasoma to sacrifice him to a tree spirit. In doing so, he overcomes massive obstacles, with giant strides, walking over horses and elephants. The individual episodes of Sutasoma's abduction are separated by trees in the image. Besides serving as a structural function for the sequence of events, they simultaneously fulfill a decorative purpose, breaking up the red background, as flowers or ornaments do elsewhere.