Dimbulagala, once called ‘Gunner's Quoin’ by the British, is the most prominent ridge in the plains of the lower reaches of the Mahaweli Ganga. The isolated mountain range located 15 km southeast of Polonnaruwa measures about 5 km (3 miles) in length and 2.5 km in width. With an altitude of 543 m, Dimbulagala is the highest peak in Polonnaruwa District.

Situated on the opposite side of Sri Lanka’s largest river and therefore historically belonging to the principalities of the island's southeastern lowlands (Rohana) and not to the realm of the Anuradhapura kings (Rajarata), the quite remote Dimbulagala ridge was an abode of reclusive forest-dwelling monks during the entire Anuradhapura period. An architecturally more prestigious monastic complex of the Pabbata Vihara type was built in the late Anuradhapura period, indicating that Dimbulagala had become a focal point of a local section of educated village monks, too. In the Polonnaruwa period, however, Dimbulagala was a monastic centre of utmost importance for the history of Theravada Buddhism. Actually, in the 12th and 13th century it was the most important monastery outside the capital, of significance even for Buddhist Orders of Southeast Asian nations.

Today, Dimbulagala is a secluded location again, an outlying area of Sri Lanka’s Cultural Triangle. This is to say, it’s not crowded with tourists, though Dimbulagala can easily be reached on day trips from both the cultural tourist hub Polonnaruwa and the East Coast’s largest beach hotel cluster, Pasikudah. The tranquility of this important heritage site may come to a surprise, as there is a lot to see here. There are at least five pretty charming and quite diverse places of interest at the northern, western and southern flanks of the range, namely the classical excavation site now known as Namal Pukuna, a large Amarapura Nikaya monastery with a museum, the ancient Pulligoda cave paintings and, last not least, the spectacularly located rock shelters of Maravidiya and Vee Atuwa. Seeing all of those attractions requires an entire day at least. Dimbulagala is also a perfect area for hiking tours and even for climbing.

Situated on the opposite side of Sri Lanka’s largest river and therefore historically belonging to the principalities of the island's southeastern lowlands (Rohana) and not to the realm of the Anuradhapura kings (Rajarata), the quite remote Dimbulagala ridge was an abode of reclusive forest-dwelling monks during the entire Anuradhapura period. An architecturally more prestigious monastic complex of the Pabbata Vihara type was built in the late Anuradhapura period, indicating that Dimbulagala had become a focal point of a local section of educated village monks, too. In the Polonnaruwa period, however, Dimbulagala was a monastic centre of utmost importance for the history of Theravada Buddhism. Actually, in the 12th and 13th century it was the most important monastery outside the capital, of significance even for Buddhist Orders of Southeast Asian nations.

Today, Dimbulagala is a secluded location again, an outlying area of Sri Lanka’s Cultural Triangle. This is to say, it’s not crowded with tourists, though Dimbulagala can easily be reached on day trips from both the cultural tourist hub Polonnaruwa and the East Coast’s largest beach hotel cluster, Pasikudah. The tranquility of this important heritage site may come to a surprise, as there is a lot to see here. There are at least five pretty charming and quite diverse places of interest at the northern, western and southern flanks of the range, namely the classical excavation site now known as Namal Pukuna, a large Amarapura Nikaya monastery with a museum, the ancient Pulligoda cave paintings and, last not least, the spectacularly located rock shelters of Maravidiya and Vee Atuwa. Seeing all of those attractions requires an entire day at least. Dimbulagala is also a perfect area for hiking tours and even for climbing.

You can find descriptions and images of Dimbulagala's places of interest below the comprehensive historical section, just scroll down or click here or choose from the following list of Dimbulagala's visiting sites:

Dimbulagala Mountain - Namal Pokuna archaeological site -

Dimbulagala Monastery - Akasa Chetiya - Maravidiya Caves - Pulligoda frescos

Dimbulagala Monastery - Akasa Chetiya - Maravidiya Caves - Pulligoda frescos

Location of Dimbulagala

Dimbulaga is situated about 15 km southeast of Pollonaruwa, as the crow flies, and 27 km by road. The road from Polonnaruwa crosses the small Flood Plains National Park. Within the park boundary the Mahaweli River is traversed by the Manampitiya Bridge, with a length of 300 m this is the longest river bridge in Sri Lanka. (Only the coastal Kinniya bridge across the mouth of Mahaweli Ganga is larger.) The Manampitiya Bridge is situated at the historical ford known as Kacchaka, which was once the main link between the two core areas of the ancient Sinhalese civilization, Rajarata and Rohana.

The monastery of Dimbulagala is in 10 km distance from the village of Manampitiya, which is at the main road A11 (Maradankadawala-Habarana-Polonnaruwa-Thirukkondaiadimadu). Pasikudah at the East Coast is in 65 km distance and Mahiyangana is 70 km to the south. The north gate of the large Maduru Oya National Park is 38 km to the south-southeast of Dimbulagala.

The monastery of Dimbulagala is in 10 km distance from the village of Manampitiya, which is at the main road A11 (Maradankadawala-Habarana-Polonnaruwa-Thirukkondaiadimadu). Pasikudah at the East Coast is in 65 km distance and Mahiyangana is 70 km to the south. The north gate of the large Maduru Oya National Park is 38 km to the south-southeast of Dimbulagala.

Names of Dimbulagala

The modern Sinhala name 'Dimbulagala' is pronounced 'Dimbulaegele' by putting the main stress on the antepenultimate syllable 'lae'.

The ancient names of Dimbulagala known from Pali literature and inscriptions are ‚Dhumarakkha Pabbata‘ and ‚Udumbara Giri‘, both ‚Pabbata‘ and ‚Giri‘ being words for ‚hill‘. The Pali term ‚Dhumarakkha Pabbata‘ is given in Sri Lanka’s chronicles. It seems to have been the name of Dimbulagala during the entire Anuradhapura period, whereas 'Udumbara Giri' is the preferred name in the Polonnaruwa period and also known from second millenium chronicles of Southeast Asia. Instead of ‘Udumbara Giri’ also the names ‘Udumbarasala Pabbata’ or ‘Dumbara Pabbata’ or ‘Dola Pabbata’ can occur.

‚Dhuma-rakkha‘, the older name, literally means ‚smoke-demon’ and may refer to the clouds often seen caught by the mountain resp. to the aboriginal inhabitants of this densely forested area.

In contrast‚ ‚Udumbara‘ is a highly significant religious term which often refers to a mythical tree that is believed to blossom only once every thousand years. In Mahayana Buddhist Sutras it has become a symbol of rare events such as the appearance of a Buddha on earth. But it can also refer to the lotus flower. In Sanskrit literature, the term ‚Udumbara‘ usually means the Indian fig tree, also known as Cluster fig tree (Ficus racemosa), which is native to tropical areas of Asia and Australia. The namegiving characteristic feature of this species are tightly packed clusters of figs growing very close to the trunk and not at the branches of the tree. The bark is used as Ayurvedic medicine. In Theravada Buddhism each Buddha is represented by a specific Indian tree, the Udumbara fig tree being the iconographic symbol of Buddha Konagama. Konagama is the second Buddha of our present aeon, the Bhadra-Kalpa (Buddha Gautama Shakyamuni being the fourth in this Kalpa). A hermitage called ‚Udumbarika‘ is mentioned in the Pali canon as a place where the Buddha gave a discourse to an ascetic that the merits of the non-ascetic Middle Way outweighs ascetic practices (25th Sutta of the Digha-Nikaya).

The meaning of the Sinhala term ‚Dimbula Gala‘ is slightly similar to that of the Pali term ‚Udumbara Giri‘. ‚Gala‘ is a characteristic Sinhalese word not known from other Indian languages. It may have originated in the language of the aboriginal Veddahs (Wedda people). ‚Gala‘ is by far the most common suffix of Sri Lankan toponyms (compare ‚Moneragala‘, ‚Mulkirigala‘, ‚Atthanagala‘ etc.). It refers to rocks and boulders but also to hills, pretty similar to the Sinhala term ‚Giri‘ derived from Sanskrit. The meaning of ‚Dimbula‘ is most probably ‚area of woodapple trees‘ (both ‚dimbul‘ and ‚divul‘ refer to Limonia acidissima).

Another name, used in legends about Dimbulagala, is the the Sanskrit term ‘Yakshapuraya’. The corresponding Pali name would be ‘Yakkhapura’, translating to “demon city”. The Adiwasi village of Yakpuraya (Yakkuaray) situated closed to Dimbulagala is believed to be the centre of the ancient Yaksha Kingdom.

In the colonial period the Dimbulagala range was called 'Gunner's Quoin'. This expressive English term, however, has dropped out of use after independence from British rule. Originally, 'quoins' (pronounced like 'coins') are stone blocks at the exterior angle of a building, not only corner stones but all blocks of the vertical edges, laid in alternate directions in each layer to stabilize the walls. The English name of the mountain range in Sri Lanka is derived from the artillery jargon, in which a 'quoin' is a wedge fixing the gun carriage.

Don't be confused, there is more than one rock called 'Gunners' Quoin', though only one of them, Dimbulagala, is in Sri Lanka. Two clear-clut rocks named 'Gunner's Quoin' are known in Australia, one in the very north and the other one in the very south of the continent. Australia's northern Gunner's Quoin is part of the Garig Gunag Barlu National Park at the Van Diemen Golf in the Northern Territory. The rock is situated 180 km northwest of Darwin, as the crow flies. Australia's more famous Gunner's Quoin, however, is on the island of Tasmania. This is a prominent dolorite cliff situated only 10 km north of the island state capital, Hobart, near Madmans Hill on the opposite side of River Derwent. It's visible from the hillsides of the city. There is yet another Gunner's Quoin in Mauritius, namely a small rocky island with vertical cliffs, just 4 km north of Cap Malheureux, the northernmost point of the main island of Mauritius. The equally common French name of the said rocky island, which has been declared a nature reserve, is Coin de Mire.

The ancient names of Dimbulagala known from Pali literature and inscriptions are ‚Dhumarakkha Pabbata‘ and ‚Udumbara Giri‘, both ‚Pabbata‘ and ‚Giri‘ being words for ‚hill‘. The Pali term ‚Dhumarakkha Pabbata‘ is given in Sri Lanka’s chronicles. It seems to have been the name of Dimbulagala during the entire Anuradhapura period, whereas 'Udumbara Giri' is the preferred name in the Polonnaruwa period and also known from second millenium chronicles of Southeast Asia. Instead of ‘Udumbara Giri’ also the names ‘Udumbarasala Pabbata’ or ‘Dumbara Pabbata’ or ‘Dola Pabbata’ can occur.

‚Dhuma-rakkha‘, the older name, literally means ‚smoke-demon’ and may refer to the clouds often seen caught by the mountain resp. to the aboriginal inhabitants of this densely forested area.

In contrast‚ ‚Udumbara‘ is a highly significant religious term which often refers to a mythical tree that is believed to blossom only once every thousand years. In Mahayana Buddhist Sutras it has become a symbol of rare events such as the appearance of a Buddha on earth. But it can also refer to the lotus flower. In Sanskrit literature, the term ‚Udumbara‘ usually means the Indian fig tree, also known as Cluster fig tree (Ficus racemosa), which is native to tropical areas of Asia and Australia. The namegiving characteristic feature of this species are tightly packed clusters of figs growing very close to the trunk and not at the branches of the tree. The bark is used as Ayurvedic medicine. In Theravada Buddhism each Buddha is represented by a specific Indian tree, the Udumbara fig tree being the iconographic symbol of Buddha Konagama. Konagama is the second Buddha of our present aeon, the Bhadra-Kalpa (Buddha Gautama Shakyamuni being the fourth in this Kalpa). A hermitage called ‚Udumbarika‘ is mentioned in the Pali canon as a place where the Buddha gave a discourse to an ascetic that the merits of the non-ascetic Middle Way outweighs ascetic practices (25th Sutta of the Digha-Nikaya).

The meaning of the Sinhala term ‚Dimbula Gala‘ is slightly similar to that of the Pali term ‚Udumbara Giri‘. ‚Gala‘ is a characteristic Sinhalese word not known from other Indian languages. It may have originated in the language of the aboriginal Veddahs (Wedda people). ‚Gala‘ is by far the most common suffix of Sri Lankan toponyms (compare ‚Moneragala‘, ‚Mulkirigala‘, ‚Atthanagala‘ etc.). It refers to rocks and boulders but also to hills, pretty similar to the Sinhala term ‚Giri‘ derived from Sanskrit. The meaning of ‚Dimbula‘ is most probably ‚area of woodapple trees‘ (both ‚dimbul‘ and ‚divul‘ refer to Limonia acidissima).

Another name, used in legends about Dimbulagala, is the the Sanskrit term ‘Yakshapuraya’. The corresponding Pali name would be ‘Yakkhapura’, translating to “demon city”. The Adiwasi village of Yakpuraya (Yakkuaray) situated closed to Dimbulagala is believed to be the centre of the ancient Yaksha Kingdom.

In the colonial period the Dimbulagala range was called 'Gunner's Quoin'. This expressive English term, however, has dropped out of use after independence from British rule. Originally, 'quoins' (pronounced like 'coins') are stone blocks at the exterior angle of a building, not only corner stones but all blocks of the vertical edges, laid in alternate directions in each layer to stabilize the walls. The English name of the mountain range in Sri Lanka is derived from the artillery jargon, in which a 'quoin' is a wedge fixing the gun carriage.

Don't be confused, there is more than one rock called 'Gunners' Quoin', though only one of them, Dimbulagala, is in Sri Lanka. Two clear-clut rocks named 'Gunner's Quoin' are known in Australia, one in the very north and the other one in the very south of the continent. Australia's northern Gunner's Quoin is part of the Garig Gunag Barlu National Park at the Van Diemen Golf in the Northern Territory. The rock is situated 180 km northwest of Darwin, as the crow flies. Australia's more famous Gunner's Quoin, however, is on the island of Tasmania. This is a prominent dolorite cliff situated only 10 km north of the island state capital, Hobart, near Madmans Hill on the opposite side of River Derwent. It's visible from the hillsides of the city. There is yet another Gunner's Quoin in Mauritius, namely a small rocky island with vertical cliffs, just 4 km north of Cap Malheureux, the northernmost point of the main island of Mauritius. The equally common French name of the said rocky island, which has been declared a nature reserve, is Coin de Mire.

History of Dimbulagala

Since the very beginnings of Sri Lanka’s Buddhist period in the 3rd century BC, hermits or small groups of reclusive monks have retreated to the forests of the Dimbulagala ridge. It was a perfect refuge, as it was rarely attacked by foreign invaders. Due to its secluded location the mountain range almost continuously served as a shelter of Buddhist monks, it has probably never been completely abandoned. By the way, this means that Dimbulagala is a sacred site inhabited by monks for a longer period than any place in the western world.

This article will discuss in some detail the role Dimbulagala played in the history of Theravada Buddhism in the 12th to 14th century - during the period in which Buddhism lost its last strongholds in India.

This article will discuss in some detail the role Dimbulagala played in the history of Theravada Buddhism in the 12th to 14th century - during the period in which Buddhism lost its last strongholds in India.

Pre-Buddhist period

Some caves of the Dimbulagala ridge bear traces of stone-age paintings, presumably from the palaeololithic Balangoda culture or from the Veddhas, who are considered descendents of the Balangoda men. Anyway, Dimbulagala belongs to the settlement area of aboriginal Veddah tribes till the present day.

The chronicles start the story of Sri Lanka by narrating the visits of the Budddha and the arrival of the first Sinhalese King, Vijaya, from India. The latter event is said to have occurred exactly at the day of the demise of the Buddha.

Prior to the introduction of Buddhism, there has already been a century of Sinhalese history of the island. The most important king of this earliest Sinhalese period is Pandukabhaya, who chose Anuradhapura as his capital - which it was destined to be for almost one and a half millennia. The records of the Mahavamsa chronicle mention Dimbulagala, then named ‚Dhumarakkha Pabbata‘, in connection with the campaign of Pandukabhaya against his rivals. The story that the mountain of Dimbulagala served as his army camp for a while may have a historical kernel, as Pandukabhaya, when fighting for the crown, seems to have been supported by inhabitants of this region east of the great river Mahaweli Ganga.

The chronicles start the story of Sri Lanka by narrating the visits of the Budddha and the arrival of the first Sinhalese King, Vijaya, from India. The latter event is said to have occurred exactly at the day of the demise of the Buddha.

Prior to the introduction of Buddhism, there has already been a century of Sinhalese history of the island. The most important king of this earliest Sinhalese period is Pandukabhaya, who chose Anuradhapura as his capital - which it was destined to be for almost one and a half millennia. The records of the Mahavamsa chronicle mention Dimbulagala, then named ‚Dhumarakkha Pabbata‘, in connection with the campaign of Pandukabhaya against his rivals. The story that the mountain of Dimbulagala served as his army camp for a while may have a historical kernel, as Pandukabhaya, when fighting for the crown, seems to have been supported by inhabitants of this region east of the great river Mahaweli Ganga.

Excursus: Pandukabhaya in Dimbulagala

Legend has it that the mountain had been the residence of demons in prehistoric times. In the chronicles of Sri Lanka, the island’s inhabitants of the pre-Singhalese period are only known demons and snakes (Rakkhas and Nagas).

After the immigration of the Sinhalese, though still in the pre-Buddhist period, Dimbulagala could have been a hideout of the semi-legendary Pandukabhaya, the famous later king who, according to the chronicles, for the first time made Anuradhapura the capital of the island. Pandukabhaya, being of royal descent, had to take refuge in the jungles, as his maternal uncles, regarding him as a rival for the throne, attempted to kill him. It was the help of the aboriginals, the abovementioned demons, that Pandukabhaya finally managed to defeat his adversaries.

The story is told in the 10th chapter of the Mahavamsa as follows:

“Then, with his great army, Pandukabhaya marched to the further bank of the Ganga towards the Dola Pabbata. There he sojourned four years. When his uncles were told of this, they marched there, leaving the king behind, to combat him. When they had fortified a camp near the Dhumarakkha Pabbata, they fought a battle with their nephew. But the nephew forced the uncles’ retreat to the other side of the river. Having forced them to flee, he stayed in their camp for two years.”

Two different mountains at the opposite side of the Mahaweli Ganga are mentioned in this quote from the Mahavamsa, namely Dola Pabbata and Dhumarakkha Pabbata. The former, also known as Dolanga, may be the highest peak of today’s Maduru Oya National Park belonging to the historical Bintenne region. A village of the name Dolgalveva in this area is mentioned in the 1901 census. This peak is roughly 50 km south of Dimbulagala, also close to the Mahaweli river banks and on the same side. The Dola Mountain was the base of Pandukabhaya, whereas the Dhumarakkha Mountain mentioned in the chronicle originally served as the army camp of his uncles to attack him. They were not succesful. Pandukabhaya managed to capture their stronghold at Dhummarakkha Pabbata alias Dimbulagala and to force them to retreat across the Mahaweli river. He then turned Dimbulagala into his own headquarters. During the four years that Pandukabhaya spends here he is said to have been making preparations for the final battle. The location of this mountaion is given as being close to the main ford. There is only one noticeable peak in this area, namely Dimbulagala. Hence, it’s highly likely that the Dhummarakkha Pabbata of the Mahavamsa chronicle is the very ridge that is known as Dimbulagala today.

After having defeated his uncles at this place, Dhummarakkha Pabbata alias Dimbulagala, it served as Pandukabhaya’s own army camp. Pandukabhaya’s wife is said to have given birth to the later King Mutasiva in one of the rock shelters of Dimbulagala.

There is another episode of the Pandukabhaya story the setting of which is this mountain. Though already married to a princess, the rebel hero falls in love with a local female demon, a Rakkhini called Chetiya, who was used to wander around in this are. After she was observed taking a bath, Pandukabhaya’s companions told him about her beauty and he became eager to catch her. This turned out to be difficult due to her demonic power. As she managed to flee again and again, Pandukabhaya had to hunt her at the mountain as well as at the nearby river alternately. Using magic, he finally caught her. In order to appease him, she promised to help him to conquer the kingdom of his uncles. Chetiya indeed plays a decisive role in the final stage of the war. The setting of the final battle is in the very heart of the kingdom, at the mountain of Arittha Pabbata, today known as Ritigala. This is the highest peak of the cultural triangle and located halfway between Polonnaruwa and Anuradhapura. At Ritigala, where Pandukabhayas army camped for seven years, even longer than at Dimbulagala, Chetiya advises Pandukabhaya to use a bit of cunning. He shall pretend to surrender by sending his insignia, but then attack his uncles. At the beginning of that last battle it is Chetiya, demoness if Dimbulagala, who starts the fight with a warrior’s cry that then is taken up by Pandukabhaya’s soldiers.

There may be a historical truth as the kernel of the Pandukabhaya legend. The base of his attack on the Sinhalese heartland was on the right bank of the river. This southeastern side of the Mahaweli Ganga, as said, is the region of ancient Rohana (Ruhuna), which actually served as a starting point for campaigns to conquer or reconquer the Anuradhapura heartland very often in the next one and a half millenniums to come, becoming a typical pattern of Sri Lanka’s ancient history. Remarkably, Pandukabhaya’s father Gamini is said to have been from Rohana. The Pandukabhaya legend also stresses the significance of various demons as assistants of Pandukabhaya. This aspect of the story may indicate that the original inhabitants of the island played a role in gaining the throne for the first Anuradhapura king, who himself was of Sinhalese birth but dependent on local helpers when fighting against his Sinhalese rivals.

After the immigration of the Sinhalese, though still in the pre-Buddhist period, Dimbulagala could have been a hideout of the semi-legendary Pandukabhaya, the famous later king who, according to the chronicles, for the first time made Anuradhapura the capital of the island. Pandukabhaya, being of royal descent, had to take refuge in the jungles, as his maternal uncles, regarding him as a rival for the throne, attempted to kill him. It was the help of the aboriginals, the abovementioned demons, that Pandukabhaya finally managed to defeat his adversaries.

The story is told in the 10th chapter of the Mahavamsa as follows:

“Then, with his great army, Pandukabhaya marched to the further bank of the Ganga towards the Dola Pabbata. There he sojourned four years. When his uncles were told of this, they marched there, leaving the king behind, to combat him. When they had fortified a camp near the Dhumarakkha Pabbata, they fought a battle with their nephew. But the nephew forced the uncles’ retreat to the other side of the river. Having forced them to flee, he stayed in their camp for two years.”

Two different mountains at the opposite side of the Mahaweli Ganga are mentioned in this quote from the Mahavamsa, namely Dola Pabbata and Dhumarakkha Pabbata. The former, also known as Dolanga, may be the highest peak of today’s Maduru Oya National Park belonging to the historical Bintenne region. A village of the name Dolgalveva in this area is mentioned in the 1901 census. This peak is roughly 50 km south of Dimbulagala, also close to the Mahaweli river banks and on the same side. The Dola Mountain was the base of Pandukabhaya, whereas the Dhumarakkha Mountain mentioned in the chronicle originally served as the army camp of his uncles to attack him. They were not succesful. Pandukabhaya managed to capture their stronghold at Dhummarakkha Pabbata alias Dimbulagala and to force them to retreat across the Mahaweli river. He then turned Dimbulagala into his own headquarters. During the four years that Pandukabhaya spends here he is said to have been making preparations for the final battle. The location of this mountaion is given as being close to the main ford. There is only one noticeable peak in this area, namely Dimbulagala. Hence, it’s highly likely that the Dhummarakkha Pabbata of the Mahavamsa chronicle is the very ridge that is known as Dimbulagala today.

After having defeated his uncles at this place, Dhummarakkha Pabbata alias Dimbulagala, it served as Pandukabhaya’s own army camp. Pandukabhaya’s wife is said to have given birth to the later King Mutasiva in one of the rock shelters of Dimbulagala.

There is another episode of the Pandukabhaya story the setting of which is this mountain. Though already married to a princess, the rebel hero falls in love with a local female demon, a Rakkhini called Chetiya, who was used to wander around in this are. After she was observed taking a bath, Pandukabhaya’s companions told him about her beauty and he became eager to catch her. This turned out to be difficult due to her demonic power. As she managed to flee again and again, Pandukabhaya had to hunt her at the mountain as well as at the nearby river alternately. Using magic, he finally caught her. In order to appease him, she promised to help him to conquer the kingdom of his uncles. Chetiya indeed plays a decisive role in the final stage of the war. The setting of the final battle is in the very heart of the kingdom, at the mountain of Arittha Pabbata, today known as Ritigala. This is the highest peak of the cultural triangle and located halfway between Polonnaruwa and Anuradhapura. At Ritigala, where Pandukabhayas army camped for seven years, even longer than at Dimbulagala, Chetiya advises Pandukabhaya to use a bit of cunning. He shall pretend to surrender by sending his insignia, but then attack his uncles. At the beginning of that last battle it is Chetiya, demoness if Dimbulagala, who starts the fight with a warrior’s cry that then is taken up by Pandukabhaya’s soldiers.

There may be a historical truth as the kernel of the Pandukabhaya legend. The base of his attack on the Sinhalese heartland was on the right bank of the river. This southeastern side of the Mahaweli Ganga, as said, is the region of ancient Rohana (Ruhuna), which actually served as a starting point for campaigns to conquer or reconquer the Anuradhapura heartland very often in the next one and a half millenniums to come, becoming a typical pattern of Sri Lanka’s ancient history. Remarkably, Pandukabhaya’s father Gamini is said to have been from Rohana. The Pandukabhaya legend also stresses the significance of various demons as assistants of Pandukabhaya. This aspect of the story may indicate that the original inhabitants of the island played a role in gaining the throne for the first Anuradhapura king, who himself was of Sinhalese birth but dependent on local helpers when fighting against his Sinhalese rivals.

Legend has it that the victorious Pandukabhaya constructed two temples honouring his two most significant Yakkha generals, one of these Devales to the north of Anuradhapura, the other one to the east of Dimbulagala.

Early Buddhist period

The first dedication of abodes to Buddhist monks in the hills of Dimbulagala is attributed in the to no less than the first Buddhist king of Sri Lanka, Devanampiya Tissa. Buddhist reclusives indeed must have lived here already in the founding period of Buddhism in Sri Lanka, maybe even before the king of Anuradhapura adopted the religion, as the early date of Buddhist settlement at Dimbulagala in the initial period of Buddhism in Sri Lanka in the 3rd century BC is confirmed by some drip ledge inscriptions of allegedly more than a hundred rock shelters, recording royal dedications in a very early version of the Brahmi script.

A total of 500 rock shelters suitable for hermits is said to exist at the rugged Dumbulagala ridge. A much later inscription attributed to Sundaramahadevi, the wife of Vikramabahu I and mother of Gajabahu II, indeed mentions that 500 monks resided here in the early 12th century AD. The number of 500 is obviously given because of its symbolical significance in Buddhism, as it was the number of participants at the first Buddhist Council, that took place one month after the demise of the Buddha, and also the number of monks involved in the textualisation of the canonical Tipitaka in Sri Lanka.

However, there can be no doubt that already in the early Anuradhapura period (last three centuries BC) the remote mountain was famous for a high number of Arahants (Arhats). This is to say Dimbulagala was revered as the abode of Buddhist saints, those most venerated monks who were believed to have attained Nibbana (Nirvana). According to the Mahavamsa chronicle, the island’s last Arahant was Maliyadeva. He is believed to have lived in the 2nd century BC or only one or two centuries later (though even the 13th century AD is sometimes reported as his lifetime). Many local legends in Sri Lanka surround the life of this last saint of Theravda Buddhism, one also attributing him to the Dimbulagala caves. However, Arankale in Kurunegala District and Padavigampola in Kegalle District are the more famous places claiming to have served as abodes of Maliyadeva Thero.

High veneration for Dimbulagala is also evident from the belief that monks from this monastic community were involved in the textualisation of the Tipitaka, the canon of Theravada Buddhism, during the reign of King Vattagamani Abhaya in the 1st century BC. The Nikayasangraha chronicle composed in the Gampola period (14th century, or even earlier in the Kurunegala period of the late 13th and early 14th century) has it, that Kuttha Gattha Tissa (also spelt ‘Kuntagatta Tissa’ or Kattha Gattha Tissa’), the leader of the the monks who set the Pali canon into writing, was from the Thuparama in Anuradhapura, which belonged to the great Mahavihara monastery. But local tradtions have it that he originally came from Dimbulagala.

The surroundings of Dimbulagala became part of the new paddy cultivation developed under Mahasena, the most prolific king concerning irrigation schemes, as probably the Pabbatanta canal, diverting water from the Mahaweli Ganga, flowed eastword past this mountain.

A total of 500 rock shelters suitable for hermits is said to exist at the rugged Dumbulagala ridge. A much later inscription attributed to Sundaramahadevi, the wife of Vikramabahu I and mother of Gajabahu II, indeed mentions that 500 monks resided here in the early 12th century AD. The number of 500 is obviously given because of its symbolical significance in Buddhism, as it was the number of participants at the first Buddhist Council, that took place one month after the demise of the Buddha, and also the number of monks involved in the textualisation of the canonical Tipitaka in Sri Lanka.

However, there can be no doubt that already in the early Anuradhapura period (last three centuries BC) the remote mountain was famous for a high number of Arahants (Arhats). This is to say Dimbulagala was revered as the abode of Buddhist saints, those most venerated monks who were believed to have attained Nibbana (Nirvana). According to the Mahavamsa chronicle, the island’s last Arahant was Maliyadeva. He is believed to have lived in the 2nd century BC or only one or two centuries later (though even the 13th century AD is sometimes reported as his lifetime). Many local legends in Sri Lanka surround the life of this last saint of Theravda Buddhism, one also attributing him to the Dimbulagala caves. However, Arankale in Kurunegala District and Padavigampola in Kegalle District are the more famous places claiming to have served as abodes of Maliyadeva Thero.

High veneration for Dimbulagala is also evident from the belief that monks from this monastic community were involved in the textualisation of the Tipitaka, the canon of Theravada Buddhism, during the reign of King Vattagamani Abhaya in the 1st century BC. The Nikayasangraha chronicle composed in the Gampola period (14th century, or even earlier in the Kurunegala period of the late 13th and early 14th century) has it, that Kuttha Gattha Tissa (also spelt ‘Kuntagatta Tissa’ or Kattha Gattha Tissa’), the leader of the the monks who set the Pali canon into writing, was from the Thuparama in Anuradhapura, which belonged to the great Mahavihara monastery. But local tradtions have it that he originally came from Dimbulagala.

The surroundings of Dimbulagala became part of the new paddy cultivation developed under Mahasena, the most prolific king concerning irrigation schemes, as probably the Pabbatanta canal, diverting water from the Mahaweli Ganga, flowed eastword past this mountain.

First constructions in the later Anuradhapura period

A new monastery founded at this mountain ridge is attributed to the King Mahanama of the early 5th century. By the way, this was a period of literal productivity, as it is the time of the composition of the island’s first Pali chronicle, the Dipavamsa, as well as the report of the Chinese pilgrim, Faxian, who studied in Anuradhapura, as well as the classical Pali commentaries and the Visudhimagga compendium of the most significant church father of Theravada Buddhism, Bhuddhghosa, who lived in Anuradhapura, too. The Mahavamsatika, a Mahavamsa commentary originally composed around the 6th century AD, praises the forest monks of Udumbaragiri, today’s Dimbulagala, for their scholarship and piety.

Apart from the rock shelters that had served as monks’ abodes right from the beginnings, Vihara stone and brick structures from the Anuradhapura period and the early Polonnaruwa period are scattered all over the ridge. This building program was probably initiated during the reign of King Mahanama. It was a common practice in Sri Lanka that new monastic buildings were donated by kings at sites that had already been inhabited by previously cave-dwelling monks. Constructing new of monastic buildings in a more systematic pattern at earlier forest dwelling places of Buddhist monks became a common practice in the later Anuradhapura period. The ruins that can be seen today at the Namal Pokuna complex may partly date back to the reign of King Mahanama. However, most of the buildings are from the second half of the first millennium BC.

Apart from the rock shelters that had served as monks’ abodes right from the beginnings, Vihara stone and brick structures from the Anuradhapura period and the early Polonnaruwa period are scattered all over the ridge. This building program was probably initiated during the reign of King Mahanama. It was a common practice in Sri Lanka that new monastic buildings were donated by kings at sites that had already been inhabited by previously cave-dwelling monks. Constructing new of monastic buildings in a more systematic pattern at earlier forest dwelling places of Buddhist monks became a common practice in the later Anuradhapura period. The ruins that can be seen today at the Namal Pokuna complex may partly date back to the reign of King Mahanama. However, most of the buildings are from the second half of the first millennium BC.

Chola interregnum and Vijayabahu I

During the period of occupation in the 11th century, when most parts of the island were ruled by the Tamil Chola Empire from the mainland India, the Buddhist monastery of Dimbulagala was affected negatively due to neglect by the new political strongmen, as they were mainly Hindu. Furthermore, the main garrison of the Chola army was based in Polonnaruwa, seat of the Cholöa gouverneur, in only short distance from Dimbulagala.

The restorer of the Sinhala rule over the island, Vijayabahu I, who managed to finally drive out the Cholas completely, nevertheless chose Polonnaruwa as his residence, too. As a Buddhist ruler he was engaged in restoring the Sangha, the Buddhist Order. He did so with the help of monks from Myanmar (Birma), whose line of successession was introduced for this purpose. Vijayabahu was all the more concerned to revive the large Dimbulagala monastery in close proximity to his residence. In particular, he is credited with restoring the buildings of the complex that is now known as Namal Pokuna.

During the following period of civil war, lasting almost half a century, monastic discipline in Sri Lanka deteriorated due to a lack of patronage and royal oversight. Many monks had mistresses and children and little knowledge of their religion. And they were landholders more than clergymen. To put in the words of the chronicles: their ambition was to ‘fill their bellies’.

The restorer of the Sinhala rule over the island, Vijayabahu I, who managed to finally drive out the Cholas completely, nevertheless chose Polonnaruwa as his residence, too. As a Buddhist ruler he was engaged in restoring the Sangha, the Buddhist Order. He did so with the help of monks from Myanmar (Birma), whose line of successession was introduced for this purpose. Vijayabahu was all the more concerned to revive the large Dimbulagala monastery in close proximity to his residence. In particular, he is credited with restoring the buildings of the complex that is now known as Namal Pokuna.

During the following period of civil war, lasting almost half a century, monastic discipline in Sri Lanka deteriorated due to a lack of patronage and royal oversight. Many monks had mistresses and children and little knowledge of their religion. And they were landholders more than clergymen. To put in the words of the chronicles: their ambition was to ‘fill their bellies’.

Parakramabahu the Great and his Sangha Reform

In this worst period of demise of Buddhism on the island, the monks of Dimbulagala however earned the reputation of observing and keeping alive the Vinaya (canonical rules of monastic disciplne). The fall of the Buddhist Order began, when Vijayabahu’s son Vikramabahu managed to ascend the thrown, although the Sangha had supported his rivals. Vikramabahu deprived the monasteries of a large portion of their temporalities in the core region of the kingdom. The discipline of the monks in the major settlement areas deteriorated mainly due to lack of royal patronage. As said, the Sangha also suffered from the then ensuing period of civil wars. Monks aiming to uphold the monastic rules had to resort to secluded places. During the first half of the 12th century, Dimbulagala thereby became the spiritual centre of forest-dwelling reclusives. They not only remained steadfast in following the Vinaya rules of monastic life. According to the chroncles, Dimbulagala became a centre of learning and literacy, too. In this early Polonnaruwa period the abovementioned epigraphic evidence confirms Dimbulagala to have been the home of 500 monks. Surprisingly, the said inscription was drawn up on behalf of the impious Vikramabahu’s wife Sundaramahadevi, a princess from India’s Kalinga kingdom. The foreign woman proved to be the main benefactor supporting the monastery of Dimbulagala, also initiating new major construction works at the site. Actually, most of the structures that can be seen at Namal Pokuna, are from the first half of the 12th century. Commencing in this time of monastic decline in the core settlement areas, the remote Dimbulagala became the island’s centre of religious studies, too.

In this said period of otherwise islandwide decline of the Buddhist Sangha, Dimbulagala’s head priest or inofficial abbot Mahakassapa Thera (Maha Kashyapa Thero) had earned the fame of being the leading figure among the only remaining disciplined and learned monks. This is why he was charged to take control of the subsequent reform process of the island’s entire Sangha. (The Sangha is Buddhist church, it's also called ‘Buddha Sasana’ in the Pali tradition, ‘Sangha’ can mean both the Buddhist Order in a more narrow sense or the community of all Buddhists, monks and nons and lay people alike, in a wider sense). It was in the reign of no less than Polonnaruwa’s most renowned king, Parakramabahu I (1253-86), that Dimbulagala, then known as Udumbaragiri, reached the peak phase of its influence and impact on Theravada Buddhism. The heydays of the monastery lasted for about two centuries to come.

|

According to the famous Gal Vihara inscription in Polonnaruwa, Mahakassapa Mahathera of Udambaragiri Vihara (Dimbulagala Maha Kashyapa Thero), served King Parakramabahu as a right-hand man. In particular, Mahakassapa Thera was the driving force behind the cleansing and unifying of the Order. The monastic reform was organized as a conference of all fraternities in Polonnaruwa, taking place in 1155/56. All monks living on the island were summoned to the council in the capital by royal decree. In large gatherings, celebrated not far away from the royal palace, new monks were fully ordained with great ceremonial. But on the other hand, many hundreds of former monks of doubtful reputation were disrobed already at the conference, this is to say: they were expelled from the Sangha. The respective verdicts were pronounced by Dimbulagala Mahakassapa Thera, though other immaculate Mahatheras, leaders of various remote monasteries, were involved in the reform process, too.

Furthermore, numerous former monks were downgraded to novice status. One reason for this reclassification of several monks as novices was that their earlier full ordination was considered invalid, as one the clergymen who had served as witnesses at that former ordination ceremony was now considered to have been of doubtful reputation at the time of the former ordination (see grey box: Cleansing the Order). The other reason for this procedure was to make the ancient Mahavihara line of ordination the only legitimate one in Sri Lanka, by forcing the downgraded monks who had been ordained in other lines such as those of Abhayagiri and Jetavanarama to receive a renewed ordination, integrating them in the Mahavihara fraternitity. Actually, the ambition as well as the result of these measures was the termination of all fraternities that had previously been rivals of the Mahavihara. In consequence, the Theravada orthodoxy, which had been upheld by the Mahavihara exclusively, became the only surviving form of Buddhism in Sri Lanka. Eight fraternities of the Sangha, which had originated from the three large Nikayas of the Anuradhapura period, were united into a single Nikaya, a new Nikaya in the old Mahavihara tradition. Another result of the Sangha reform supervised by King Parakramabahu was a hierarchal structure, with Dimbulagala Mahakassapa Thera as the supreme man of the cloth. He earned the title of ‘Sangharaja’, which translates to “king of the Buddhist Order’. The king and Mahakassapa Thera also issued a code of conduct, called Kathikavatha, for the guidance of the Buddhist monks. It was adopted by the council and made mandatory for clergymen by royal order, non-adherence leading to expulsion from the Sangha. This new code of additional disciplinary rules was inscribed on the abovementioned Galvihara rock. From a Buddhist perspective, in a strict canonical approach, no layman, not even a king, is allowed to interfere in affairs of the Sangha (Budddhasana). However, in Theravada tradition the monastic reforms initiated by Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century BC served as a classic example of the involvement of a pious king in the cleansing of the Order. In such a Sangha reform process the king, formally speaking, served only as a patron of the assembly and as the power enforcing the decisions made solely by the leaders of the Sangha, as according to canonical Vinaya rules only fully and validly ordained monks, such as Mahakassapa Thera in the case of the Polonnaruwa concil, were permitted to be the agents of establishing internal rules of conduct for securing monastic discipline and to expel deviating monks respectively. Restoring the discipline of the clergy was not the only measure taken to reestablish its standing a the leading spiritual force of the island nation. New monasteries were founded and the reforms also improved the educational standards of the Sangha. Due to both its proximity to the capital and its tranquility at the opposite side of the Mahaweli, particularly Dimbulagala was further developed into a center of Buddhist scholarship. The monks learned lessons in three languages, Pali, the sacred language of the Theravada canon and commentaries, Sinhala, the local language, and also Sanskrit, the classical language of Indian culture. In the aftermath of the reform council, hundreds of monks from abroad came to Sri Lanka for their Buddhist studies. Many of them may well have done so in Dimbulagala, as its Udumbaragiri monastery was still an epicenter of Buddhist learning, besides the capital, and therefore of great appeal for students from all parts of the island and from foreign countries alike. King Parakrambahu’s and Dimbulagala Mahakassapa’s monastic reform is of utmost historical significance, as it is this event that made the orthodox Theravada the only legitimate school of Buddhism in Sri Lanka - and subsequently in Southeast Asia as well. In a sense, it’s only since the said Polonnaruwa council and just due to this monastic reform, which made the Mahavihara line of ordination the only legitimate one, that Sri Lanka has become a Theravada country and has earned her reputation of being the stronghold of Theravada orthodoxy till the present day. Indeed, the Mahavihara line has become the only surviving one in all Theravada countries in the course of the next three centuries. |

Excursus: Mahavihara orthodoxy of TheravadaThe Mahavihara was been the very first monastery on the island, founded by Missionary Mahinda in the time of Emperor Ashoka. Mahinda is not only the root of the line of ordination in Sri Lanka, he is also credited with having brought the (then oral) knowledge of the Pali canon as well as reliable commentaries from India. In the course of the centuries, the Mahavihara Nikaya was the only one - of Anuradhapura’s three major Nikayas - that continued to insist on the orthodoxy of exclusively those teachings brought by Mahinda - whereas the larger Abhayagiri monastery, for example, became a centre of studying Mahayana texts of later origin, too. Hence, the exclusivity of the Mahavihara line, due to the Sangha reform in the reign of Parakramabhu the Great, is the reason why Theravada orthodoxy became the sole form of Buddhism on the island. A few centuries later on, Sri Lanka’s Mahavihara tradition also became the only Buddhist school in Southeast Asia. Buddhism in Myanmar was diverse, including Theravadic and Mahayanistic and Tantric schools side by side, before Anawrahta of Bagan in the 11th century introduced Theravada Buddhism from the Mon people. The Theravada line of ordination prevalent among the Mon, however, was not brought by Mahinda but by other Buddhist missionaries sent by the same Emperor Ashoka, namely Sona and Guttika. It was only in the 12th century, the time of King Parakramabhu in Sri Lanka, that the Mahinda line of ordination - and thereby Sri Lanka’s Mahavihara tradtion - was introduced in Myanmar, remarkably by a monk, who himself was a Mon but received higher ordination in Sri Lanka (see grey box: Chappada). After his return to Myanmar, he called his newly established fraternity ‘Sihala’, as it originated from the Sinhalese people of Sri Lanka. For three centuries, the earlier Mon tradtion recurring to Sona and Guttika and the new Sinhalese line of ordination installed by Mahinda coexisted - or were rivals - in Myanmar. In the 15th century, however, a former monk from the Sinhalese line became king of the Mon. This famous King Dhammacheti decided to have all monks ordained or re-ordained in the Sinhalese line exclusively. For this purpose he sent a delegation to Sri Lanka who received higher ordination at the Kelani river. This is the major reason why Sri Lanka’s Mahavihara tradition is the only surviving line of Theravada in Myanmar. (The reason why this Sinhalese line of ordination prevailed in Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia, too, can be seen in the grey box ‘Udumbaragiri Mahasami’) Excursus: Sanskrit tradition of Sri LankaIn Sri Lanka Sanskrit has not been in use for religious texts, but similar to the role of Latin in medieval and early modern Europe, it was, though not spoken as a native language any morem, the transregional scientific language for scientific treatise in entire South Asia. In Sri Lanka, treatises on Ayurvedic medicine in particular were composed in Sanskrit. Later on, also Sinhalese poetry made use of Sanskrit verses. Among Theravada Buddhist nations, the tradition of studying and writing Sanskrit texts is unique to the Buddhist Order of Sri Lanka. In contrast, older Sanskrit texts were completely replaced by Pali versions in Myanmar, after Theravada Buddhism had been introduced. Even some inscriptions in Sri Lanka are written in Sanskrit, though the Devanagari script is rarely used for it. As in the case of some southern Indian nations, the classical Devanagari was occasionally replaced by local scripts. During the Polonnaruwa period the use of Sanskrit became more common than in the preceding Anuradhapura period. This can be seen even from the name of the most famous Pollanurua king. “Parakramabahu”, the name used in the Pali chronicles, is actually a Sanskit name or Sanskritisation of the Pali name “Parakkhamabahu”. |

Excursus: Buddhist Council in Polonnaruwa?

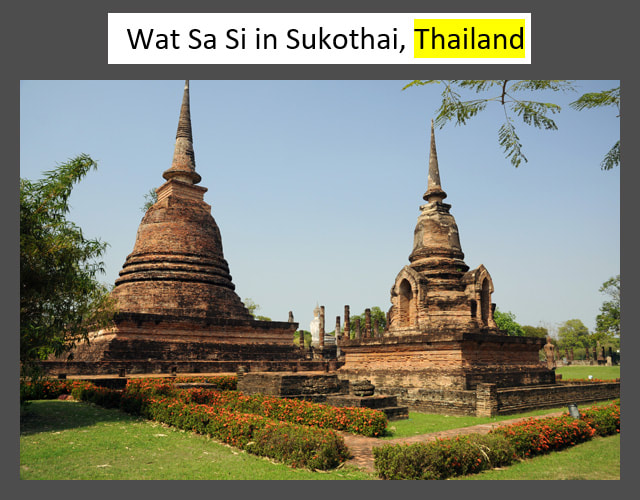

The recitation of the entire Tipitaka scriptures, a practice characteristic of Buddhist councils (Sanghayanas), is the reason why the monks’ assembly at Polonnaruwa is sometimes counted as a Theravada Council. This seems to be the case particularly in the tradition of the former kingdom of Lanna (Lan-Na) in today’s northern Thailand, as there was a Buddhist council counted as the 8th, which was celebrated under the auspices of King Tilokarat at Wat Chet Yod in 1477.

However, usually the Council initiated by King Mindon and held in his newly established capital Mandalay in 1871 is counted the 5th of Theravada Buddhism.

How can this be? Theravada Buddhist schools of both Lan-Na and Mandalay belonged to the same orthodox Mahavihara tradition!

The reason for the divergent numbers of councils is as follows: Today’s traditional Theravada view is that only one Buddhist Council was held in Sri Lanka, viz. the 4th at Aluvihara in the time of Vattagamani Abhaya. But there is already some confusion, if this was rather the 5th, after already 4 assemblies reciting the canon had been held in India. But what matters in the case of the “Lanna Council” being the 8th is this: If all reciting ceremonies securing the corpus of the Tipitaka are counted as Buddhist Councils, there must have been 4 such events in Sri Lanka according to the island’s chronicles. One of them, as said, was elebrated in Polonnaruwa at the time of Parakrama Bahu’s and Dimbulagala Maha Tissa’s Sangha reform – and therefore considered to be a Sanghayana according to the view of the Theravada Buddhist clergy in the late kingdom of Lanna.

However, usually the Council initiated by King Mindon and held in his newly established capital Mandalay in 1871 is counted the 5th of Theravada Buddhism.

How can this be? Theravada Buddhist schools of both Lan-Na and Mandalay belonged to the same orthodox Mahavihara tradition!

The reason for the divergent numbers of councils is as follows: Today’s traditional Theravada view is that only one Buddhist Council was held in Sri Lanka, viz. the 4th at Aluvihara in the time of Vattagamani Abhaya. But there is already some confusion, if this was rather the 5th, after already 4 assemblies reciting the canon had been held in India. But what matters in the case of the “Lanna Council” being the 8th is this: If all reciting ceremonies securing the corpus of the Tipitaka are counted as Buddhist Councils, there must have been 4 such events in Sri Lanka according to the island’s chronicles. One of them, as said, was elebrated in Polonnaruwa at the time of Parakrama Bahu’s and Dimbulagala Maha Tissa’s Sangha reform – and therefore considered to be a Sanghayana according to the view of the Theravada Buddhist clergy in the late kingdom of Lanna.

Excursus: Cleansing the Order and Validity of Ordination

‘Cleansing of the Order’ is a term meaning excluding monks who violated the Vinaya rules. This was crucial for securing a proper line of ordination in the first place. To understand the problem of having a valid and undisputed ordination, one has to consider this: Among the 227 Patimokkha forming the backbone of Vinaya, there are four fundamental rules called Parajikas (defeats), namely prohibition of sexual intercourse, stealing, killing and telling lies concerning one’s achievements of spiritual states. Violation of one of these four Parajika rules results in immediate and irrevocable expulsion from the Sangha. As a result of this rule, the validity of the line of ordinations – and hence the legitimacy of the entire Buddhist Sangha! - could become questionable in times of declining discipline. The crucial point is this: In case of Parajika sins, the status of being a monk is lost instantly - just at the time the offence is committed! - particularly at the very moment of sexual intercourse. This question - which was the point in time when the ecclesiastical status was lost? - is highly relevant, as this is not the date of a later verdict in the monks’ assembly. As said, the date of being no monk any more is the date of the offence, not of the trial or of the 'taking-off of the robes' (which is the official term for expulsion from the Sangha). Because of this question of date, there is a lineage validity problem in the Buddhist Order, due to the time period in between the offence and the verdict. Imagine: Maybe the verdict is spoken after many years, just because the offence has not come to anyone’s notice for such a long period. In the meantime, however, the offender has nevertheless already lost his status as a monk! - although maybe nobody else is aware of this. This actually lost ecclesistical status now has consequences for the validity of the lineage of ordination: In case the offender was one of the required five witnesses of the higher ordination of a novice, this new monk’s full ordination in this case is actually invalid! – although nobody might be aware of it. To put it in other words: The Buddhist ordination is dependent on the presence of five witnesses who are Buddhist monks in the legal sense of this word. Someone, who commited a Parajika offense actually is no monk any more according to the Vinaya rules. So, in case one of those witnesses only still wears a monk’s robe though he already committed the high crime of sexual intercourse, he in the juridical sense is not a monk any more and thereby not a witness of the ordination ceremony any more - and therefore the new ordination is void!

This means, the reputation of the Sangha as an institution of ordained persons is at stake in times of rumours about sexual relationships of monks. The standing of the Sangha is not only just tarnished by those particular offenders, rather it's completely undermined, due to the lack of validity of new ordinations during that period the Parajika offenders participated in ordination ceremonies. This is why a monastic reform not only requires the expulsion of offenders - taking off their robes - but also securing an undisputed line of ordination.

This can be done by introducing a new valid line with the help of external monks whose reputation is impeccable at that point in time. And this is why monks from Sri Lanka introduced lineages from Southeast Asia after periods of declining discipline - and the other way around. As a result of this, all of today's lineages in Sri Lanka are from Thailand or Myanmar, whereas all lineages in Thailand and Myanmar and Laos and Cambodia are from Sri Lanka. How can this be? In the 11th century Vijayabahu reestablished ordinations wit the help of monks from Myanmar, though without renouncing the island's Mahinda lineage. But in the aftermath of the Sangha reform of Parakramabahu in the 12th century, Myanmar and other Southeast Asian nations introduced the Sinhalese lineage, this was done in the period from the 12th to 15th century. In turn, one part of the Sri Lankan monks received a renewed ordination lineage from Thailand in the 18th and another part from Myanmar in the 19th century. At the present time, all Buddhist Orders in Southeast Asia are called 'Sinhala' or 'Mahavihara' (first monastery of Anuradhapura), whereas all Nikayas (fraternities or sections) in Sri Lanka are called Syam (Siamese) or Burmese (Myanmarese).

This means, the reputation of the Sangha as an institution of ordained persons is at stake in times of rumours about sexual relationships of monks. The standing of the Sangha is not only just tarnished by those particular offenders, rather it's completely undermined, due to the lack of validity of new ordinations during that period the Parajika offenders participated in ordination ceremonies. This is why a monastic reform not only requires the expulsion of offenders - taking off their robes - but also securing an undisputed line of ordination.

This can be done by introducing a new valid line with the help of external monks whose reputation is impeccable at that point in time. And this is why monks from Sri Lanka introduced lineages from Southeast Asia after periods of declining discipline - and the other way around. As a result of this, all of today's lineages in Sri Lanka are from Thailand or Myanmar, whereas all lineages in Thailand and Myanmar and Laos and Cambodia are from Sri Lanka. How can this be? In the 11th century Vijayabahu reestablished ordinations wit the help of monks from Myanmar, though without renouncing the island's Mahinda lineage. But in the aftermath of the Sangha reform of Parakramabahu in the 12th century, Myanmar and other Southeast Asian nations introduced the Sinhalese lineage, this was done in the period from the 12th to 15th century. In turn, one part of the Sri Lankan monks received a renewed ordination lineage from Thailand in the 18th and another part from Myanmar in the 19th century. At the present time, all Buddhist Orders in Southeast Asia are called 'Sinhala' or 'Mahavihara' (first monastery of Anuradhapura), whereas all Nikayas (fraternities or sections) in Sri Lanka are called Syam (Siamese) or Burmese (Myanmarese).

Dimbulagala's contribution to Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia

One result of King Parakramabahu’s and Dimbulagala Mahakassapa Thera’s Sangha reform was a highly improved standard of conduct, which increased the fame of the island’s Sangha and, within an astonishingly short period of time, attracted foreign Buddhist monks. Clergymen from Myanmar (Burma) visited the island only a few years after the Polonnaruwa council, two successive Sangharajas (primates) of the Buddhist Sangha of Bagan (Pagan) in Myanmar being among them. One reason for this development was that Sri Lanka promised to be a save haven for Buddhist monks in a time of turmoil in their country of origin, Myanmar. After the death of Shin Arahan, a monk from the Mon kingdom who established Theravada Buddhism in Bagan under Myanmar’s famous King Anawarahta and continued to be the religious leader under subsequent kings, Panthagu was the next in line of the Sangharajas of the Bagan kingdom. According to the chronicles of Myanmar, which however were composed only many centuries later on, Panthagu fled to Sri Lanka, because the infamous Narathu gained the throne by poisoning his brother, who had been invited by Panthagu to come to the capital to settle the dispute peacefully. Narathu is also said to have constrained some Buddhist monks to leave the Sangha. Instead of becoming laymen, some of them preferred to follow the example of Panthagu and escaped to Sri Lanka.

with a cuboid chamber called harmika atop the bell-shaped dome, the Sapada Pagoda founded by the first monk ordained in Sri Lanka is Myanmar's earliest stupa in the Sinhalese style (photo courtesy of Günter Schönlein)

with a cuboid chamber called harmika atop the bell-shaped dome, the Sapada Pagoda founded by the first monk ordained in Sri Lanka is Myanmar's earliest stupa in the Sinhalese style (photo courtesy of Günter Schönlein)

Soon afterwards, Panthagu’s successor Uttarajiva visited Sri Lanka, too. This turned out to be a crucial event in the history of Theravada Buddhism, as the only Samanera (novice) accompanying Uttarajiva played a pivotal role in establishing Sri Lanka’s Mahavihara line of ordination in Southeast Asia. The novice was ordained in Sri Lankan in a ceremony joined by local Sinhalese monks. After his return to Myanmar he established a new Buddhist Nikaya called the Sihala Order (see Excursus: Mahavihara orthodoxy), which later on became the sole lineage in Myanmar as well as in all other Theravada nations of Southeast Asia. The name of this young man who arrived in Sri Lanka in the 1170s, is Chappada (see Excursus: Chappada). There are divergent spellings of his name in inscriptions and in much later chronicles of Myanmar, with various transliterations for each of them. This is why the name of the said novice can be given as Chappada or Chapata or Japata or Sapada or even Sagata. When Uttarajiva returned to Myanmar, the newly ordained Chappada stayed in Sri Lanka for another decade. This is chronicled in the 15th-century Kalyani rock inscription in Bago (Pegu), Lower Myanmar. It is highly likely that Chappada continued his studies not only in the capital Polonnaruwa but also in Dimbulagala, as it is said that on his return to Southeast Asia he was accompanied by other learned Bikkhus (monks), who had been residing in the Udumbaragiri monastery alias Dimbulagala.

Excursus: Chappada alias Sapada alias Sagata

The famous Kalyani inscriptions drawn up by King Dhammacheti in his capital Bago as well as the later chronicles of Myanmar give accounts of how Uttarajiva, the Sangharaja of Myanmar, and some of his disciples visited Sri Lanka on a pilgrimage. Chappata, belonging to the Mon people of Lower Myanmar who have a longer Theravada tradition than Bagan in Upper Myanmar, was the only novice among the disciples who accompanied Uttarajiva on his voyage to Sri Lanka. According to the Kalyani inscriptions, the arrival took place only six years after King Parakramabahu’s Sangha reform. The Buddhist clergymen from Myanmar are said to have been warmly welcomed on their arrival on the island. The respective lineages descending from Mahinda in Sri Lanka and Sona and Uttara in Myanmar were mutually respected. This means, neither Sri Lankan monks nor the visitors from Myanmar filed claims of superiority but respected the line of ordination of the other nation. This can be seen from the fact, reported in the Kalyani inscription, that the Upasampada (full ordination) of the novice Chappata was performed with both parties represented as witnesses, neither of them insisting that the ordained monks of the other lineage had to receive a new ordination, too. However, Chappata was thereby received into the Sinhalese Order of Sri Lanka, in the name of Saddhamma Jothipala. After finalizing their pilgrimage to the Bo Tree and the Tooth Relic, the most sacred sites of Sri Lanka, Uttarajiva and his delegation returned to Myanmar, leaving behind only Chappata. He stayed in Sri Lanka for ten more years, studying the Tipitaka and the commentaries in Sinhalese monasteries. It was only on his return to Myanmar that Chappata decided to insist on the superiority of his Sinhalese lineage, which led to the establishment of his separate fraternity in Bagan. For being able to introduce a new line of ordination in Myanmar he had to be accompanied by four more monks of the Sinhalese Order from Sri Lanka, because according to the canonical Vinaya rules five witnesses are required for a higher ordination of new monks.

Excursus: Tamalinda, Khmer prince and Sinhalese missionary

Remarkably, the four companions of Chappata, though all of them were ordained in the Sinhalese line and lived in Dimbulagala, are said to have been from diverse countries of origin. Only one companion, named Rahula, was a Sinhalese monk from Sri Lanka. Ananda was a Tamil monk from the former Pallava capital Kanchipuram, which centuries ago had been an important centre of Buddhist learning. Sivali was a native of Tamralipti, the most important seaport of Bengal before the arrival of the Europeans. Tamalinda was a Khmer prince, a son of the king of Cambodia. This may come to a surprise, as in the 12th century the Khmers of Angkor were the arch rivals of the Bagan Empire of Myanmar. (Presumably, close ties between Sri Lanka and Cambodia had been the reason why a short-termed military naval confict between Parakramabahu and rulers in Myanmar ensued in the 1150s, before relations became cordial again soon afterwards.)

The Khmer among those five missionaries ordained in Sri Lanka, Tamalinda, is said to have been the son of no less than Angkor’s King Jayavarman VII, who was the most prolific temple builder in Khmer history, his hall mark being the famous face-towers of Angkor and other sites in Cambodia. Jayavarman VII, who introduced Buddhism to the Khmer empire, however, was a Mahayanist. His form of Buddhism differed much from that of Sri Lanka. In contrast, his son Tamalinda, as a representative of the Sihala Order in the Mahavihara lineage, was an exponent of Theravada orthodoxy. Actually, after the reign of Jayavarman VII (and a subsequent period of Hindu revival at the royal court in Angkor in the mid 13th century) Cambodia finally became a Theravada Buddhist country. It’s uncertain whether already the monk and former prince Tamalinda, who had studied in Dimbulagala, contributed to the establishment of a Theravada line of ordination in Cambodia.

But there is no doubt that the Sinhalese lineage introduced by him and his companions, after arriving from Sri Lanka, turned out to be more successful in the neighbouring countries in the region of the Menam river than in Myanmar's core region of Bagan at the Irawaddy river. At least during the entire initial century of their activities in Southeast Asia, those missionaries of the Sinhalese Order had a higher impact on religious developments that took place outside of Upper Myanmar.

The royal court of Cambodia embraced Theravada as official religion of the kingdom not before the 14th century. Prior to that, Theravada had not been introduced on princely initiatives. Rather, the reason for the success of Theravada Buddhism in Cambodia was winning supporters among the common people in rural areas. Unlike Mahayana Buddhism, which was once imposed by the empire’s elites in the late 12th century, Theravada, preached by monks from neighbouring countries in the 13th century, had become popular just with peasants, before being adopted by the elites, too. In other words: The introduction of Shivaism as well as Vishnuism as well as Mayayana Buddhism from India was a top-to-bottom process promulgated by mighty kings, but never actually replacing the animistic cults of the peasantry. In contrast, Theravada Buddhism from Sri Lanka became a grassroots movement in Cambodia in times of political turmoil, because Theravada was, firstly, an educational system improving living standards of villagers despite of the lack of royal authority and, secondly, perfectly able to integrate their local cults instead of replacing them. In a bottom-to-top process in the late medieval period Theravada Buddhism became the most wide-spread and finally official religion of Cambodia.

The Khmer among those five missionaries ordained in Sri Lanka, Tamalinda, is said to have been the son of no less than Angkor’s King Jayavarman VII, who was the most prolific temple builder in Khmer history, his hall mark being the famous face-towers of Angkor and other sites in Cambodia. Jayavarman VII, who introduced Buddhism to the Khmer empire, however, was a Mahayanist. His form of Buddhism differed much from that of Sri Lanka. In contrast, his son Tamalinda, as a representative of the Sihala Order in the Mahavihara lineage, was an exponent of Theravada orthodoxy. Actually, after the reign of Jayavarman VII (and a subsequent period of Hindu revival at the royal court in Angkor in the mid 13th century) Cambodia finally became a Theravada Buddhist country. It’s uncertain whether already the monk and former prince Tamalinda, who had studied in Dimbulagala, contributed to the establishment of a Theravada line of ordination in Cambodia.

But there is no doubt that the Sinhalese lineage introduced by him and his companions, after arriving from Sri Lanka, turned out to be more successful in the neighbouring countries in the region of the Menam river than in Myanmar's core region of Bagan at the Irawaddy river. At least during the entire initial century of their activities in Southeast Asia, those missionaries of the Sinhalese Order had a higher impact on religious developments that took place outside of Upper Myanmar.

The royal court of Cambodia embraced Theravada as official religion of the kingdom not before the 14th century. Prior to that, Theravada had not been introduced on princely initiatives. Rather, the reason for the success of Theravada Buddhism in Cambodia was winning supporters among the common people in rural areas. Unlike Mahayana Buddhism, which was once imposed by the empire’s elites in the late 12th century, Theravada, preached by monks from neighbouring countries in the 13th century, had become popular just with peasants, before being adopted by the elites, too. In other words: The introduction of Shivaism as well as Vishnuism as well as Mayayana Buddhism from India was a top-to-bottom process promulgated by mighty kings, but never actually replacing the animistic cults of the peasantry. In contrast, Theravada Buddhism from Sri Lanka became a grassroots movement in Cambodia in times of political turmoil, because Theravada was, firstly, an educational system improving living standards of villagers despite of the lack of royal authority and, secondly, perfectly able to integrate their local cults instead of replacing them. In a bottom-to-top process in the late medieval period Theravada Buddhism became the most wide-spread and finally official religion of Cambodia.

Dimbulagala in the aftermath of the Polonnaruwa period

The Sangha reform of Parakramabahu the Great in the 1260th was a starting point. In the second half of the Polonnaruwa period and in the subsequent Dambadeniya period Sri Lanka became the standard bearer of Theravada orthodoxie, the Dimbulagala monastery being a main exponent of this development. This medieval era of monastic reform and literary productivity in the 12th and 13th century was pivotal in shaping the institutional and intellectual and social traditions of Theravada Buddhism not only in Sri Lanka but also in Southeast Asia. The role of Dimbulagala alias Udumbaragiri in this period of reforms cannot be underestimated. Historiography commonly tends to praise the most powerful kings of Polonnaruwa and Dambadeniya, Parakramabahu I resp. Parakramabahu II., as the initiators of those monastic reforms that resulted in the predominance of the ancient Theravada school. However, the Buddhist monks themselves might deserve more credits for those medieval reforms than the abovementioned famous kings, as one might well argue that it was a time of instability in the 12th and 13th century of Sri Lankan history – with only short periods of strong royal control over the island - that motivated monks to reorganize their monastic order themselves. As a result of this, just because monastic institutions were involved in the administration of the island, they also contributed significantly to stabilizing the political situation. This is to say: monastic developments were a root cause of the abovementioned kings becoming powerful – instead of strong Sinhalese kings being the cause of the said Buddhist revival. Dimbulagala was able to play a crucial role in this significant process in Asian history, as it was both an extraordinarily large monastery and a remote one and therefore much less affected by political turbulences than the major monasteries in the capitals Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa.

Contradictory to the above statements, local legends have it that the heydays of Dimbulagala ended with the devastating invasion of Kalingha Magha, which began in 1215. The country suffered from a severe famine at the same time, taking the lives of a thousand monks in the Mahaweli area.

However, the decline of the irrigated rice cultivation and main settlement areas of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa in the aftermath of Kalinga Magha’s lootings was not a sudden or short-termed event. In general, the abandonement of the former core region of the ancient Singhalese civilization was a gradual process. The invasion of Kalinga Magha marks the beginning of this period, but it's not the root cause. Devastating wars had occurred earlier on, too. But Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa always managed to recover from them. This was not the case in the 13th century any more. Other cities now emerged as the new Sinhalese strongholds further southwest. The island’s former heartland became a tribal area instead. However, this does not mean that it was suddenly left by Buddhist monks. Quite the contrary, remote areas became the preferred abodes of the Arannavasin branch, which was formally established in the Dambadeniya period in the middle of the 13th century. Dambadeniya was not in control of the the Mahaweli region, this is why the chronicles composed in Dambadeniya lost sight of Dimbulagala. Nevertheless, it must have remained to be a very renowned monastery for at least one more century. This can be seen from the fact that till the mid 14th century Dimbulagala had a big impact on the devolpment of Budddhism in Southeast Asia (see below).

However, the decline of the irrigated rice cultivation and main settlement areas of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa in the aftermath of Kalinga Magha’s lootings was not a sudden or short-termed event. In general, the abandonement of the former core region of the ancient Singhalese civilization was a gradual process. The invasion of Kalinga Magha marks the beginning of this period, but it's not the root cause. Devastating wars had occurred earlier on, too. But Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa always managed to recover from them. This was not the case in the 13th century any more. Other cities now emerged as the new Sinhalese strongholds further southwest. The island’s former heartland became a tribal area instead. However, this does not mean that it was suddenly left by Buddhist monks. Quite the contrary, remote areas became the preferred abodes of the Arannavasin branch, which was formally established in the Dambadeniya period in the middle of the 13th century. Dambadeniya was not in control of the the Mahaweli region, this is why the chronicles composed in Dambadeniya lost sight of Dimbulagala. Nevertheless, it must have remained to be a very renowned monastery for at least one more century. This can be seen from the fact that till the mid 14th century Dimbulagala had a big impact on the devolpment of Budddhism in Southeast Asia (see below).

Dimbulagala monks may well have been involved in reforms - and the issuing of a new new Kathikayatha code of conduct - in the Dambadeniya period, too, dispite the fact that Parakramabahu II for the purpose of restoring the Sangha invited monks mainly from foreign nations, viz. from the South Indian Chola region and from South Asia’s Malay Peninsula. Parakramabahu II established a new central monastery for forest-dwelling monks at Palabatgala near Adam’s Peak. The king held reclusives in high esteem, more than ordinary village monks. Actually, it is only since the Dambadeniya period that the divisions of forest monks (Arannavasins) and village monks (Gamavasins) got an official status in the Nikayas of Theravada Buddhism, although forest-dwelling reclusive monks had already been settling in remote areas and held in high esteem in the Anuradhapura period, with Dimbulagala being their largest settlement in the Polonnaruwa time. In the mid 13th century Dimbulagala was situated close to the area occupied by foreign invaders, this is why it seems to have been outside the territory of effective control of the new Sinhalese capital Dambadeniya, which is located further to the southwest of the former Sinhalese core regions of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa. This does not mean that Dimbulagala was not an important forest monastery any more. This is only to say it was outside the scope of royal patronage during the Dambadeniya period.

Though the Sinhalese kings were much less powerful those days, the island of Sri Lanka has been looked upon as the religious metropolis of Theravada Buddhism from the 13th century onwards. The reason is that in this period this monastic religion was entirely wiped out from India by Muslim invaders destroying the last Buddhist strongholds on the mainland, both the monasteries and universities in Bengal (Bihar belonged to Bengal those days). Ever since, monks from Southeast Asia eager to study the canon and the commentaries in more detail traveled to Sri Lanka instead of India.

In the 14th century Dimbulagala, then still known as Udumbaragiri, again was the fountainhead of a Theravada revival. This is known from the role a monk from this monastery played in the establishment of Theravada Buddhism in Southeast Asia, particularly in the Mon kingdom of Lower Myanmar and in the newly established kingdoms of Thailand. Only a few decades after his activities, the Sri Lankan form of Buddhism was firmly established in almost all parts of mainland Southeast Asia, except from the areas of today’s Vietnam.