The rarely visited Ramba Vihara near Embilipitiya is one of the most important excavation sites of southern Sri Lanka. It was once the temple of the city of Mahanagakula, which was of significance particularly in the 11th century AD, when Anuradhapura was occupied by the Chola empire from India.

Content of our detailed Ramba Vihara page:

Location - Name

History: Anuradhapura Period - Polonnaruwa Period - Late Middle Ages

Excursuses: Living Monastery today - Beminiteya Seya - Gajabahu Inscription - Manawalu Sandeshaya

What to see:

Archaeological Museum - Monastic Area Ruins - Bodhigara - Complex 21 - Eastern Image House

Location - Name

History: Anuradhapura Period - Polonnaruwa Period - Late Middle Ages

Excursuses: Living Monastery today - Beminiteya Seya - Gajabahu Inscription - Manawalu Sandeshaya

What to see:

Archaeological Museum - Monastic Area Ruins - Bodhigara - Complex 21 - Eastern Image House

The Ramba Vihara, also transcribed ‘Rambha Viharaya’ in the Hambantota district is both an archaeological site and a living monastery.

The complex of the Ramba Vihara ruins is much larger than the present-day monastery. In historical times, the monastic complex, however, formed only a part of an even vaster urban settlement. The new temple is therefore surrounded by a huge archaeological area. But the remnants are not spectacular. What can be seen today, are temple ruins with only foundation walls remaining and some stone pillars still standing upright.

Incidentally, the beginnings of scintific excavations in the Ramba Vihara area prompted more systematic research into the entire ancient and medieval southern kingdom of Rohana. The respective area has since been called the ‘Southern Cultural Triangle’, although its shape resembles less that of a triangle but rather a broad band alog the the southern and southeastern coast line.

With a total area of about 100 hectares covered by ancient monastic buildings and more than 30 hectares protected heritage zone, the Ramba Vihara is by far the most extensive excavation area in the southern plains of Sri Lanka. This may come to s surprise, as the archaeological site of Ramba Vihara is not as well known as other groups of ancient buildings. The reason is that the ruins of, for example, Situpahuwwa in the Yala area and Lahugala further east are better preserved and somewhat wore imposing. Nevertheless, Ramba Vihara has to be counted among the most significants remnants of the sacred architecture of the Middle Ages outside Sri Lanka’s do-called Cultural Triangle. Since only the foundations or stone pillars are the only parts of the former structure that can still be seen, the Ramba Vihara is indeed not a must-see for normal traveller. But anyone who spends his vacation in the Tangalle area or crosses the area on the way from Ratnapura or Udawalawe National Park to the southern coast should consider a short detour to look around the vast complex of the Ramba Vihara. Outside the Cultural Triangle and particularly in the Deep South, there are far and wide only a few places more suitable to gain an impression of the ancient Sinhalese civilization.

The complex of the Ramba Vihara ruins is much larger than the present-day monastery. In historical times, the monastic complex, however, formed only a part of an even vaster urban settlement. The new temple is therefore surrounded by a huge archaeological area. But the remnants are not spectacular. What can be seen today, are temple ruins with only foundation walls remaining and some stone pillars still standing upright.

Incidentally, the beginnings of scintific excavations in the Ramba Vihara area prompted more systematic research into the entire ancient and medieval southern kingdom of Rohana. The respective area has since been called the ‘Southern Cultural Triangle’, although its shape resembles less that of a triangle but rather a broad band alog the the southern and southeastern coast line.

With a total area of about 100 hectares covered by ancient monastic buildings and more than 30 hectares protected heritage zone, the Ramba Vihara is by far the most extensive excavation area in the southern plains of Sri Lanka. This may come to s surprise, as the archaeological site of Ramba Vihara is not as well known as other groups of ancient buildings. The reason is that the ruins of, for example, Situpahuwwa in the Yala area and Lahugala further east are better preserved and somewhat wore imposing. Nevertheless, Ramba Vihara has to be counted among the most significants remnants of the sacred architecture of the Middle Ages outside Sri Lanka’s do-called Cultural Triangle. Since only the foundations or stone pillars are the only parts of the former structure that can still be seen, the Ramba Vihara is indeed not a must-see for normal traveller. But anyone who spends his vacation in the Tangalle area or crosses the area on the way from Ratnapura or Udawalawe National Park to the southern coast should consider a short detour to look around the vast complex of the Ramba Vihara. Outside the Cultural Triangle and particularly in the Deep South, there are far and wide only a few places more suitable to gain an impression of the ancient Sinhalese civilization.

Location of the Ramba Vihara

|

The Ramba Vihara is situated halfway in the village of Udatota between Embilipitiya and Hambantota, more precisely, between the villages of Siyyambalangoda and Ganegoda. Although the entrance is a few hundred meters east of the main road, a tourist sign indicating the correct branch road can be found at the A18 highway only twwo kilometers south of Siyyambalangoda.

The terrain of the Ramba Vihara now lies in between the Walawe River and a western lateral channel known as Mamadala Nalikava.

|

Name of the Ramba Vihara alias Rambha Viharaya

The name of the present monastery is probably derived from the Sanskrit word "Rambha", which, next to "Kedali", is one of the terms used for “banana”. More precisely, “Rambha” means “plantain”. The English word “banana”, by the way, was introduced by the Portuguese, who adopted it from the local language at the coast of Guinea, where they first found this plant, which had spread from tropical India via Egypt to West Africa since the 6th century. The plains along the lower reaches of the river Walawa Ganga are well-known in Sri Lanka as being on of the best banana cultivation areas. The name "banana monastery" is not at all ridiculous, insofar novices are said to have preferred to study under a banana trees. Although there are other theories of origin for the monastery’s modern name, the derivation from a term meaning bananas, which are found in abundance in the surroundings, is supported by early references to the monastery as Kehelgamuwa, "Kehel" being an earlier alternative Sinhala pronunciation and spelling of "Kesel", which today is the common Sinhala term for bananas.

Ramba Vihara in the late Middle Ages

The 13th century saw the decline and fall of Polonnaruwa and the entire irrigation-based Sinhalese civilsation. But it also saw the begin of the rise of a new Sinhalese settlement area in the southwestern wet zone. Not all parts of the island were effected negatively. The heydays of the Ramba Vihara contued for another few centuries. The Padasaghara inscription from that period of crisis shows, that respected Buddhist monks assembled in the Ramba Vihara. Buddhist monks in this part of the island composed works in Pali.

A written testimony of its own kind is preserved from this period of upheaval in Sri Lanka, which shows the high esteem that Sri Lanka's Order continued to enjoy in Theravada Buddhist Southeast Asia: The Manawulu Sandeshaya, which translates to "Mahanagakula Message", is a Pali poem in around 60 verses of which 30 verses are preserved (see grey box in the right-hand column). The text refers to the abbot of a Ramba Vehera as a sender of a letter to Burma (Myanmar) to answer questions of a Buddhist leader of that country. The banana grove, which gives shade to the noble monks, is described at the begnning of this doctrinal poem. Traditionally, this work of poetry is attributed to Parakramabahu's son and short-term successor Vijayabahu II (1186-87) in order to increase its authority by claiming royal authorship. However, it is much more likely that it is rather a work from the 13th century.

A written testimony of its own kind is preserved from this period of upheaval in Sri Lanka, which shows the high esteem that Sri Lanka's Order continued to enjoy in Theravada Buddhist Southeast Asia: The Manawulu Sandeshaya, which translates to "Mahanagakula Message", is a Pali poem in around 60 verses of which 30 verses are preserved (see grey box in the right-hand column). The text refers to the abbot of a Ramba Vehera as a sender of a letter to Burma (Myanmar) to answer questions of a Buddhist leader of that country. The banana grove, which gives shade to the noble monks, is described at the begnning of this doctrinal poem. Traditionally, this work of poetry is attributed to Parakramabahu's son and short-term successor Vijayabahu II (1186-87) in order to increase its authority by claiming royal authorship. However, it is much more likely that it is rather a work from the 13th century.

What to see in Ramba Vihara Archaeological Site

The entire excavation site can be divided into three parts. Firstly, the entrance area, where the accommodations and ceremonial buildings of the present monastery are located, is also fully packed with remnants of ancient structure built of stone. Secondly, a few hundred meters to the east of today’s monastic buildings is the main complex from the Anuradhapura period. Thirdly, there is a large but barely explored area to the north of the entrance area. So far only a few sparse ruins are seen in the grove.

Archaeological Museum of Ramba ViharaHowever, it is within this northern area of the archaeological site that a provisional museum exhibiting some of the excavation finds is established, though the more important art treasures found in the Ramba Vihara complex are already brought to Colombo for safekeeping. The site of the Ramba Vihara was quite rich in artifacts, including an extraordinary white sandstone Buddha statue hollowed inside, and a precious gilded reliquary, Rattharan Karaduwa, which according to radiocarbon dating carried out in the USA is from the 8th-10th century, corresponding Sri Lanka’s late Anuradhapura period.

|

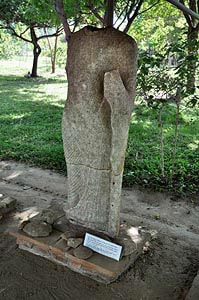

Another Buddha statue, which is man-high but without a head, is on display in the courtyard of the building, which also houses the office of archaeologists. The statue is made of white marble and dates back to the 5th-7th century. Century. It shows references to the Amaravati style, which had flourished in southern India several centuries earlier.

|

Further exhibits the museum terracotta are relief plates decorated with geese, mythological beings called Hansas (also trascribed Hamsas). They have been found in large quantities. The geese hold a plant in their mouths. On the left they are flanked by pilasters. This way, an entire frieze was originally put together in which each goose had an own panel.Further exhibits the museum terracotta are relief plates decorated with geese, mythological beings called Hansas (also trascribed Hamsas). They have been found in large quantities. The geese hold a plant in their mouths. On the left they are flanked by pilasters. This way, an entire frieze was originally put together in which each goose had an own panel.

|

|

Furthermore, you can see millstones and also urinal stones in the courtyard of the museum, the latter having a drain. Otherwise they could be considered sacred footprints, so-called Siripathulgalas.

Inside the two museum rooms, which resemble more of an arsenal of artefacts than an actual exhibition, you can see terracottas and small Buddha statues, albeit often headless. On the other hand, there is also a collection of heads without a body. As said, the interior is more an archive than a museum, as there are only few travellers coming to see it. After all, informative maps are provided for the rare visitor. |

Ancient remnants within the modern monastic area

Let us now turn to the entrance area where the monks reside today. Just in between the new monatic lodgings and the hall for religious ceremonies and the obligatory white stupa this temple area is densely packed with ruins of typical structures of sacred buildings from the Anuradhapura period.

|

You can see porticos once edged by walls made of brick. The larger stone columns are still standing upright. Some buildings have antechambers or vestibuls. The entrance and door areas are decorated, they are much more ornate than the other parts of the buidlings. Most of the structures that can be seen in this part of the archaeological site were so-called image house (Pathimagaras) and monks’ residences (Kutis), the former, serving for rituals also of lay visitors, had the abovementioned small lobbies, whereas the latter were one-room-buildings, forming the monastic living area.

|

|

Just to the right of the entrance is an elongated building. It was an image house containing a reclining Buddha statue. It was made of brick and probably plastered ans painted, but nothing remains from the sculpture. What can be seen today is only the brick foundation. The structure and its sculpture are attributed to roughly the 6th century, the mid Anuradhapura period.

|

Bodhigara, Bo-terrace, Stupa

One of the structures vlose to the modern monastic area was a Bodhigara made of brick. Instead of a Buddha statue, a Bo-tree was the object of veneration in this type of shrine. The structure from the mid Anuradhapura period was not roofed in the centre where once the tree grew. Now only the square pit can be seen, where the tree was rooted. The entire groundplan is square-shaped, an outer room allowed cicumambulating the sacred tree. Originally, there must have been altars in front of the tree in all four directions, the Buddha statues once placed there have been excavated.

|

Behind the said stupa now painted white in the modern style, there are pathes leading to the most interesting part of the excavation area.

Walking along these pathes eastwards, you will first pass a new white patio-style enclosure of a Bo-tree, a tree of enlightenment can be found in almost every modern village temple. Supplying water for the sacred tree is one of the ceremonies performed by visitors at full-moon celebrations. |

Complex 21 of the Ramba Vihara

|

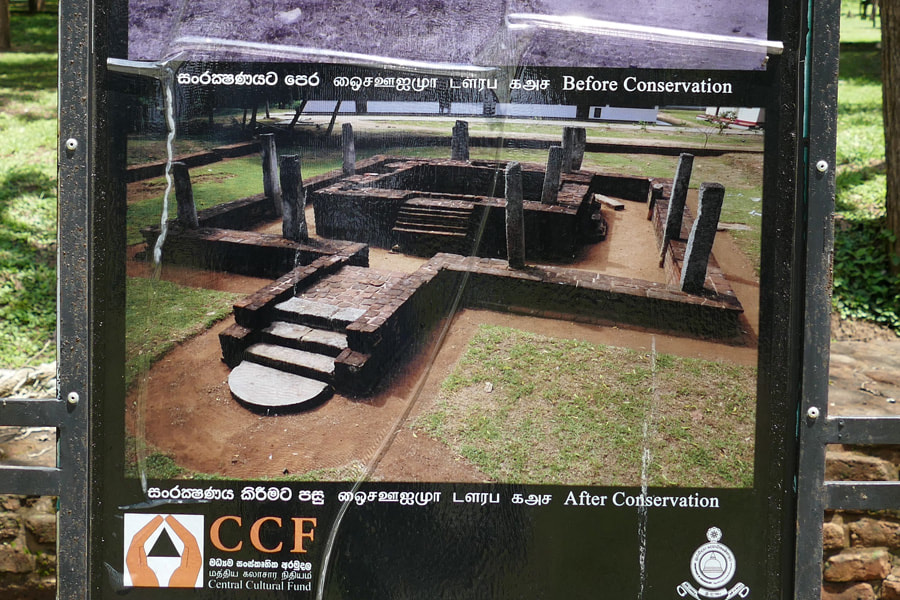

Within a pleasantly shady grove, there is a fenced complex (so-called complex 21).which due to its size and to the variety of its structures must have been the main place of worship of the ancient Ramba Vihara. The entrance of the enclosing walls of this group of Buddhist temple buildings faces east, as usual. It is highlights by an entire gatehouse, of which many stone columns can be seen standing upright. The passage way is flanked by two interior rooms.

|

|

Going straight ahead (or slightly turning to the left) one arrives at two so called image houses (Pathimagaras). This type of architecture is named after the Buddha statues which were once worshiped in the main room of sich shrine. The main cult room had a flight of vestibuls. The larger of the two image houses within this complex still has traces of colors of former paintings. The plaster once serving as undercoat of the paintings can still be seen.

|

Image house in the eastern part of the archaeological zone

|

The most beautiful image house of the Ramba Vihara archaeological site is a little bit hidden, even further in the thicket, ith a small pond named Mahanaga Pokuna behind it. But is easy to find it when following the trail eastwards, which will finally lead towards the Walawa River and Lake Ridiyagama, where you also found the foundations of a stupa.

Inside the said Pathimaghara, half-way to the not well-preserved stupa, stands the torso of an over-sized Buddha statue made of limestone, again this is a work of art inspired by the Amaravati style. This building from the mid- or late Anuradhapura period represents an archaic type of statue house, as the vestibule is of very modest dimensions. The only pillared hall in this statue house is that of the comparatively wide main room containing the image. In front of the entrance there is an extraorinarily large monolith of rectangular shspe and without any decoration, instead of a semi-circular moonstone. |

|

The image house with the statue is pretty charming, simply due to its secluded location. Some details of the are remarkable, too.

At the entrance to the patio of the Patimaghara one can see, though very small in size when compared to similar entrance decorations in the region of the Cultural Triangle, the typical temple stairway of the late Anuradhapura period, namely balustrades in the shape of curved tongues that stick out the mouths of the Makara crocodiles, as well as a diminutive guardian stele. The three steps are noteworthy, too. As with the temples of Anuradhapura, they are each decorated with three small Gana (chthonic spirit) reliefs flanked by pilasters. Although these Gana carvings are weathered, the gnoms are still clearly recognizable in cheerful dance moves. |

|

As said, the Ramba Vihara is not one of Sri Lanka's greatest heritage destination. But in the Deep South of the island, it’s definitely one of the richest and most typical excavation of a medieval monastic complex, captivating by being embedded in a living village monastery on the one hand and the lonely jungle on the other. And due to the fact that it is rarely visited, it’s still inviting to start own explorations completely undisturbed by noisy busloads of tourists.

|