Pidurangala is often visited in conjunction with the neighbouring rock of Sigiriya, as it is renowned for its panoramic views of the area, including Sigiriya itself.

Content: Location - Name - History - Cave Temple - Reclining Buddha - Prehistoric Caves - Summit - Stupa & ruins

Actually, there is a very lot to see in Pidurangala, as this rock monastery offers at least four different kinds of attractions:

- Firstly, in the plains just below the rock is a typical example of a ruined ancient monastery from the Anuradhapura period, very similar to the Pabbata Parivena type. Thereby, Pidurangala is an attraction combining natural beauty with historical and cultural significance.

- Secondly, a typical Sri Lankan cave temple with image houses in the style of the Kandyan period can be seen at the base of the rock. he main cave contains a reclining Buddha statue and several frescoes. The entire site is considered sacred by Buddhists. The monastery is inhabited by monks.

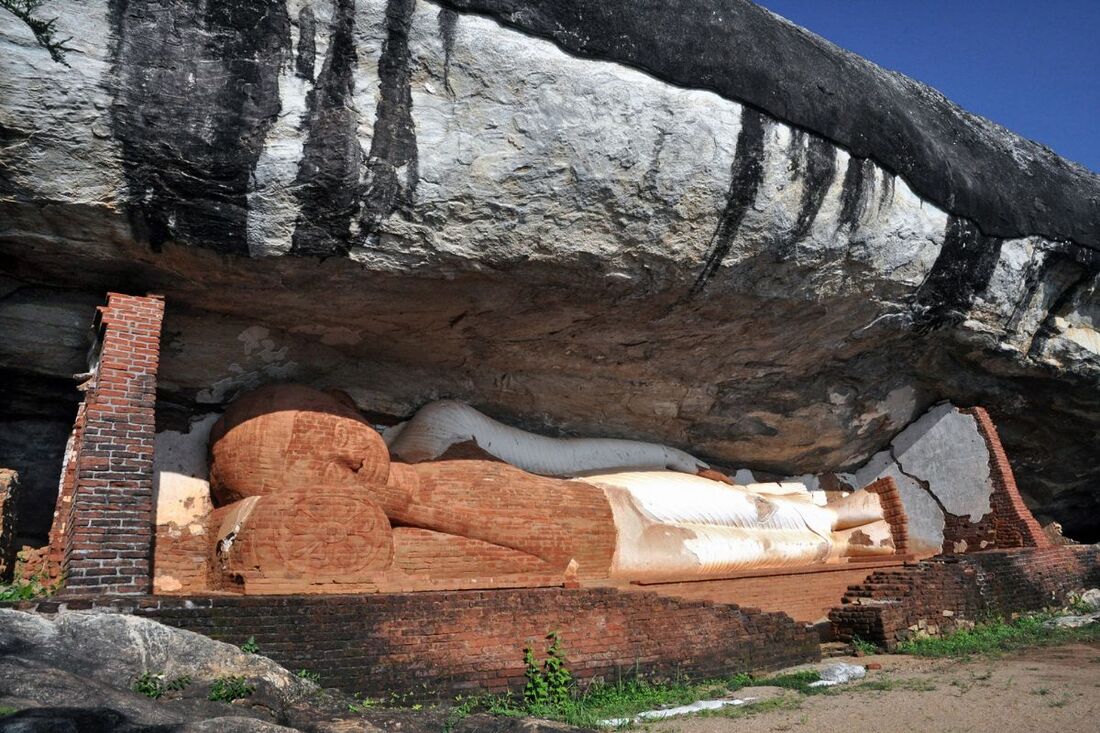

- Thirdly, a lush green jungle path, for the most part a flight of steps, runs along prehistoriy semi-caves to a large recumbent image of the Buddha, which is made of brick and stucco. Due to its location, this is actually one of the most enchanting Buddha statue on the island of Sri Lanka.

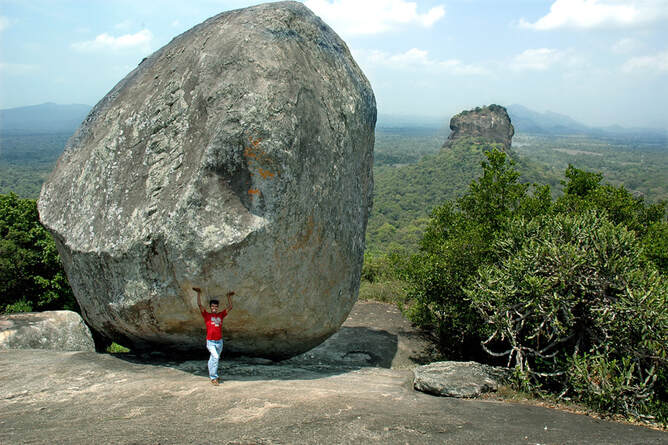

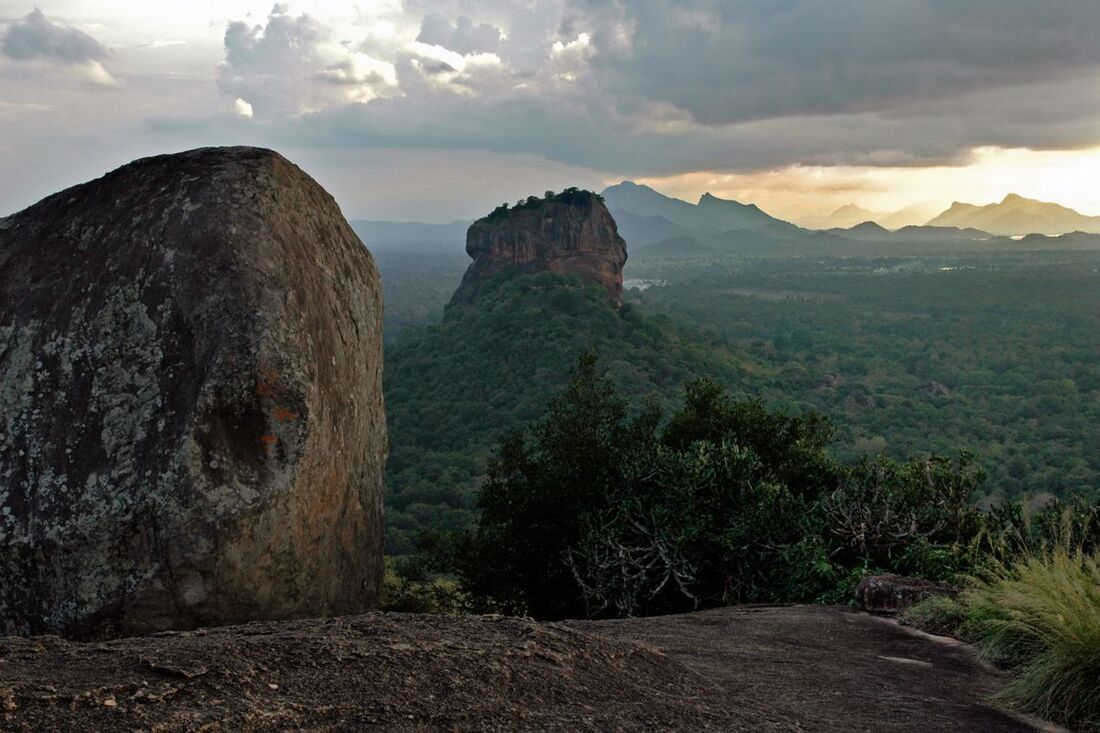

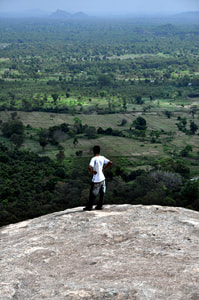

- Last not least, from there a short but steep climb leads to the top. The last part of the climb to the top is a bit challenging, involving a steep ascent where you need to use your hands, but the effort is rewarded with breathtaking views, particularly beautiful during sunrise and sunset. The 360 degree panorama from the summit plateau of Pidurangala is even more exciting than that from Sigiriya, as the steep monadnock of the Lion Rock itself can be seen from a distance. It’s the perfect viewpoint for pictures of Sigiriya and to overlook the entire central plains of Sri Lanka’s Cultural Triangle.

The breathtaking vistas from the top and the lonesome Buddha statue in the jungle are rewarding travel destinations indeed, allowing to praise Pidurangala as one of the best places to visit on the island of Sri Lanka. The best times to visit Pidurangala are early morning or late afternoon. The large sleeping Buddha in a rock niche just below the summit is best seen around 7.30 am, because it receives direct sunlight only for one hour a day.

- Firstly, in the plains just below the rock is a typical example of a ruined ancient monastery from the Anuradhapura period, very similar to the Pabbata Parivena type. Thereby, Pidurangala is an attraction combining natural beauty with historical and cultural significance.

- Secondly, a typical Sri Lankan cave temple with image houses in the style of the Kandyan period can be seen at the base of the rock. he main cave contains a reclining Buddha statue and several frescoes. The entire site is considered sacred by Buddhists. The monastery is inhabited by monks.

- Thirdly, a lush green jungle path, for the most part a flight of steps, runs along prehistoriy semi-caves to a large recumbent image of the Buddha, which is made of brick and stucco. Due to its location, this is actually one of the most enchanting Buddha statue on the island of Sri Lanka.

- Last not least, from there a short but steep climb leads to the top. The last part of the climb to the top is a bit challenging, involving a steep ascent where you need to use your hands, but the effort is rewarded with breathtaking views, particularly beautiful during sunrise and sunset. The 360 degree panorama from the summit plateau of Pidurangala is even more exciting than that from Sigiriya, as the steep monadnock of the Lion Rock itself can be seen from a distance. It’s the perfect viewpoint for pictures of Sigiriya and to overlook the entire central plains of Sri Lanka’s Cultural Triangle.

The breathtaking vistas from the top and the lonesome Buddha statue in the jungle are rewarding travel destinations indeed, allowing to praise Pidurangala as one of the best places to visit on the island of Sri Lanka. The best times to visit Pidurangala are early morning or late afternoon. The large sleeping Buddha in a rock niche just below the summit is best seen around 7.30 am, because it receives direct sunlight only for one hour a day.

Location

|

Pidurangala is a 200m high granite colossus located just one kilometer north of Sigiriya in the very center of Sri Lanka's historic region known as Cultural Triangle.

Administrationally, the rock of Pidurangala is situated in the northernmost part of Sri Lanka's Central Province and of its Matale District. The driving distance to Habarana in Anuradhapura District is only 11 km (8 miles). The gate of Minneriya National Park is in only 17.5 km (11 miles) distance by road |

Name

"Pidu" means "revered," "Ran" means "golden," and "Gala" means "rock." The name of the place is pronounced "Pidurangelle" with emphasis on the "a." An older spelling is "Piduragala." In the eighteenth century, some colonial administrators called the place "Pithurangala," which refers to the "father's rock." However, "Pidurangala" is the correct form.

History

Pidurangala is not only geographically but also historically connected to the palace city of Sigiriya. The entire area, extending beyond Dambulla, is also known as "Sigiri Bim". Settlements, monasteries, tanks, and quarries of the "Sigiri Bim" have a direct connection to Sigiriya and are integrated into the sophisticated concept of this capital, that was systematically established in the fifth century. Pidurangala was the Buddhist main monastery next to the royal residence in Sigiriya. It is said that the founder of Sigiriya, Kassapa I, visited the reclining Buddha of Pidurangala twice daily to pay his respects to him and to the monks of Pidurangala. Others claim that Kassapa bowed to the Buddha of Pidurangala from the lion's paws at the base of his palace rock in Sigiriya. Wherever this knowledge comes from.

for more historical background information about King Kassapa and the Pidurangala monastery click here...

Kassapa I (473-95), sometimes named with his Sanskrit name "Kaschyapa," is probably the most colourful figure among the Anuradhapura kings. He is the second king of the Moriya dynasty, whose name implies an origin from the Indian Maurya Emperor Ashoka. Kassapa was the elder son of King Dhatusena, the deserving founder of the dynasty after a tumultuous period of South Indian occupations of the island. As the son of a South Indian concubine from the Tamil dynasty of the Pallavas, Kassapa was not entitled to the throne. But he seized power with the help of the chief general named Migara. On Kassapa’s behalf, Migara killed the old king in a cruel way, and the rightful heir, his half-brother Moggallana, fled to South India.

The Sigiriya founder owes his title "Pithru Gathaka Kaschyapa," which means "Father-killer Kassapa," to his act of violence. It is said that Kassapa felt insecure in Anuradhapura, also because the clergy detested his brutal acts and illegitimate rule. Some researchers interpret his newly established residence in Sigiriya not only as the result of a military strategy but also as a religious innovation: a monument to a cult of kingship where the king resided in the palace on the Sigiriya rock, which was fashioned as a divine mountain, like Shiva (or Kubera) lived in a palace on Mount Meru. Additionally, the area at the foot of the Sigiriya rock had previously been inhabited by Buddhist monks and was now transformed into a representative garden city for the king, which is considered sacrilege: monastery grounds should not be secularized. It doesn't help much that the new king compensated the monks who had inhabited the caves of the Sigiriya rock with a new monastery in Pidurangala.

However, there is evidence against the idea of a king who opposed Buddhism, as he adorned Pidurangala with a magnificent monastery for an estimated 500 monks. There is little evidence that a heretical variant of Buddhism, such as Mahayana followers, was settled here, as claimed by some. While Kassapa may have attempted to introduce a new religious legitimacy, he was likely wise enough not to unnecessarily provoke the well-established Theravada Buddhism in the country with its significant economic influence on the rural population. Instead, he honoured the traditional religion of the island in Pidurangala. The first excavator of Sigiriya, Harry Charles Purvis Bell, suggested that the cloud maidens of Sigiriya turned towards Pidurangala, proposing that these famous paintings in Sri Lanka depict a procession to the monastery, with servants accompanying the court ladies bearing floral offerings to the reclining Buddha of Pidurangala. The first and most significant Sinhalese archaeologist, Senarat Paranavitana, only partially agreed with this interpretation of the cloud maidens, which is generally doubted today.

The Sigiriya founder owes his title "Pithru Gathaka Kaschyapa," which means "Father-killer Kassapa," to his act of violence. It is said that Kassapa felt insecure in Anuradhapura, also because the clergy detested his brutal acts and illegitimate rule. Some researchers interpret his newly established residence in Sigiriya not only as the result of a military strategy but also as a religious innovation: a monument to a cult of kingship where the king resided in the palace on the Sigiriya rock, which was fashioned as a divine mountain, like Shiva (or Kubera) lived in a palace on Mount Meru. Additionally, the area at the foot of the Sigiriya rock had previously been inhabited by Buddhist monks and was now transformed into a representative garden city for the king, which is considered sacrilege: monastery grounds should not be secularized. It doesn't help much that the new king compensated the monks who had inhabited the caves of the Sigiriya rock with a new monastery in Pidurangala.

However, there is evidence against the idea of a king who opposed Buddhism, as he adorned Pidurangala with a magnificent monastery for an estimated 500 monks. There is little evidence that a heretical variant of Buddhism, such as Mahayana followers, was settled here, as claimed by some. While Kassapa may have attempted to introduce a new religious legitimacy, he was likely wise enough not to unnecessarily provoke the well-established Theravada Buddhism in the country with its significant economic influence on the rural population. Instead, he honoured the traditional religion of the island in Pidurangala. The first excavator of Sigiriya, Harry Charles Purvis Bell, suggested that the cloud maidens of Sigiriya turned towards Pidurangala, proposing that these famous paintings in Sri Lanka depict a procession to the monastery, with servants accompanying the court ladies bearing floral offerings to the reclining Buddha of Pidurangala. The first and most significant Sinhalese archaeologist, Senarat Paranavitana, only partially agreed with this interpretation of the cloud maidens, which is generally doubted today.

why it's likely that one of Sri Lanka's historically most important monks and scholars was from Pidurangala can be read here...

Legend has it that the monk Mahanama, the author of the Mahavansa Chronicle, lived in Pidurangala. This is not entirely implausible. Although the Mahavansa most likely originated in the Mahavihara monastery in Anuradhapura, the commentaries on the Mahavansa say that the author belonged to a Dighasanda Parivena. This does not undermine the Mahavihara origin of the Mahavansa, as each group of buildings of the Mahavihara had its own name. Dighasanda, however, was the nickname of a general of Dutthagamani in the 2nd century BC. During that early period, there was only one major monastery in Anuradhapura: the Mahavihara. Usually, rural monasteries like Pidurangala were organizationally connected to one of the main monasteries in Anuradhapura. This might have been the connection of the Mahavihara monk Mahanama to Pidurangala. However, the author of the Mahavansa is an apocryphal figure in any case. And the monks were able to move between the different branches of their order, as can still be seen today. The fact that the author of the Mahavansa originally comes from Pidurangala is evidenced by the fact that the writing of this work dates back to the time of King Mogallana, the successor of Kassapa.

It is very likely that the monks settled by King Kassapa in Pidurangala, or at least some of them, followed the king to the new capital Sigiriya after the reign of Mogallana, who relocated of the royal residence to Anuradhapura. Certainly, at the court of the new king in Anuradhapura there would have been many influential monks as advisors who had played a role under his predecessor Kassapa and could only have done so at his residence, meaning they lived in Pidurangala before. So, the idea that the author of the Mahavansa was such a monk does not necessarily seem like a story invented later to glorify the place.

It is very likely that the monks settled by King Kassapa in Pidurangala, or at least some of them, followed the king to the new capital Sigiriya after the reign of Mogallana, who relocated of the royal residence to Anuradhapura. Certainly, at the court of the new king in Anuradhapura there would have been many influential monks as advisors who had played a role under his predecessor Kassapa and could only have done so at his residence, meaning they lived in Pidurangala before. So, the idea that the author of the Mahavansa was such a monk does not necessarily seem like a story invented later to glorify the place.

Cave Temple of Pidurangala Raja Maha Viharaya

In front of the eastern flank of the Pidurangala rock, there is another monastery. It is called "Pidurangala Raja Maha Viharaya," meaning "Royal Monastery," in memory of the fact that the ancient Pidurangala was a new foundation by a king. The current monk accommodations are new but located quite beautifully at the foot of the rock (photo).

On the terrace just above, there is the image house (photo) of the current Pidurangala monastery. This main building leans against a rock section and, again, utilizes a natural rock shelter like many other cave monasteries of the Anuradhapura period. The current masonry front of the cave dates back to 1933.

Between the corrugated iron roof of the new front and the ancient drip ledge, you can see an inscription band (photo). The surfaces chiseled under the drip ledge have always been the preferred places for the dedication inscriptions of the lay donors to the order.

Inside, the main shrine is decorated in a gaudy fashion. However, two of the five Buddha statues in the cave, which is dominated by a long reclining Buddha, are said to date back to the Anuradhapura period. They were likely made and installed during the Sigiriya era and later received their present appearance in the late 18th century through plastering and painting.

The other figures, like the paintings, are of more recent origin. The more than 6-meter-long reclining Buddha (photo) probably dates from the time of the re-establishment of this monastery in the second half of the 18th century. The core is made of bricks. This could still date back to the Sigiriya era, like the similarly styled reclining Buddha further up on the rock. Remnants of original Kandyan paintings are said to have been integrated into the current ones. You can obtain the key to this narrow image house from the monks living close-by.

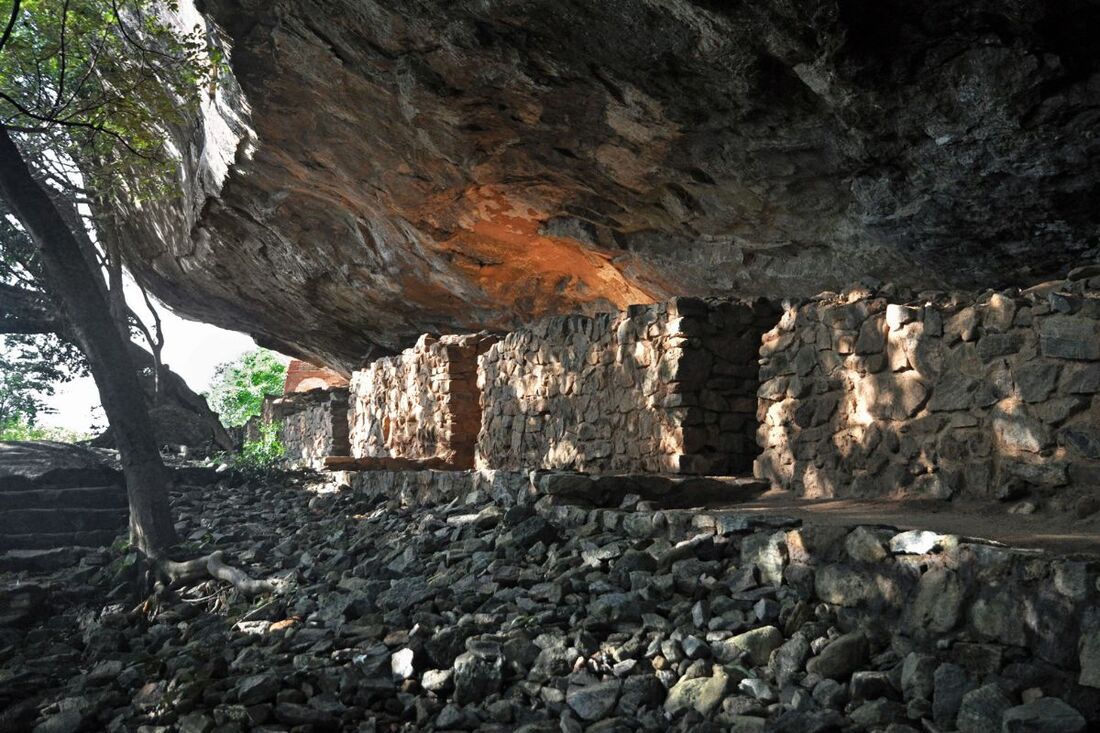

In front of the image house, a very charming jungle staircase begins. The 500 stone steps are mostly ancient. The pleasantly shaded ascent leads along massive granite rocks (photo). The first group of such rocks is located on a saddle on the northern side of the main rock. It is clearly visible here that the rock shelters were once used by inhabitants. As so often of Sri Lanka, you can see the edges of the drip ledges on the rocks above the cavities, where rainwater dripped off, preventing it from flowing into the cave interior.

Strictly speaking, the so-called caves of the forest monasteries of Sri Lanka are not real cave spaces but shelters under overhanging rocks. They are not enclosed spaces with an exit but open on one side. Therefore, they are also referred to as "half-caves." Scientists often give such caves the French name "Abri" for shelter or hut. Such shelters also attract animals. In archaeology, rock shelters play an outstanding role in researching prehistory, not only because prehistoric hunters preferred to live here, but especially because the protection provided by the rock roof preserved their traces much better than in open areas. In European prehistoric research, it was initially only under rock shelters that various layers of the soil with their respective time-specific artifacts could be clearly distinguished, helping to establish relative chronologies for the sequence of Stone Age developmental phases. The Sinhalese name for rock shelters is "Galge," literally meaning "stone house."

From the rock inscriptions at the rock niches of Pidurangala, it is known that this place has been inhabited by monks since at least the time around the birth of Christ. The dedication inscriptions were not only intended to emphasize the pious gift of the donor, which undoubtedly contributed to their better karma. They also served as donation documents, acting as seals for the vested rights of the Buddhist Order, the Sangha, so that the once-given territory could not be taken away. The inscriptions confirm a monastic use of the Pidurangala rock even before Kassapa. It 'likely that it already existed as a forest monastery of considerable size in the third century. Kassapa only expanded it, especially to create a new ceremonial center at the foot of the mountain (see below).

The upper section of the stairway runs along a total of 200 meters of rock shelter of varying depth. It is divided by walls into a dozen adjacent cave rooms, with the smaller ones at the bottom serving as living quarters for monks. Towards the top, the forest opens up, and the stairway ends at about two-thirds height of the rock. You stand on a terrace in front of the rock niches and have a wide view of the densely wooded plain to the east on the other side. Part of the terrace is of natural origin, but it was artificially extended to create a broader forecourt in front of the largest caves, which served as cult rooms. The walls supporting these terraces on the slope side are ancient. Also, three depressions were carved into the rock in this terrace area for collecting water. The largest basin at the upper end of the terrace measures 3.60 meters by 4.60 meters and surely served as a "Pokuna," a bathing facility for the monks. The smaller ones may have been cisterns for collecting drinking water.

Strictly speaking, the so-called caves of the forest monasteries of Sri Lanka are not real cave spaces but shelters under overhanging rocks. They are not enclosed spaces with an exit but open on one side. Therefore, they are also referred to as "half-caves." Scientists often give such caves the French name "Abri" for shelter or hut. Such shelters also attract animals. In archaeology, rock shelters play an outstanding role in researching prehistory, not only because prehistoric hunters preferred to live here, but especially because the protection provided by the rock roof preserved their traces much better than in open areas. In European prehistoric research, it was initially only under rock shelters that various layers of the soil with their respective time-specific artifacts could be clearly distinguished, helping to establish relative chronologies for the sequence of Stone Age developmental phases. The Sinhalese name for rock shelters is "Galge," literally meaning "stone house."

From the rock inscriptions at the rock niches of Pidurangala, it is known that this place has been inhabited by monks since at least the time around the birth of Christ. The dedication inscriptions were not only intended to emphasize the pious gift of the donor, which undoubtedly contributed to their better karma. They also served as donation documents, acting as seals for the vested rights of the Buddhist Order, the Sangha, so that the once-given territory could not be taken away. The inscriptions confirm a monastic use of the Pidurangala rock even before Kassapa. It 'likely that it already existed as a forest monastery of considerable size in the third century. Kassapa only expanded it, especially to create a new ceremonial center at the foot of the mountain (see below).

The upper section of the stairway runs along a total of 200 meters of rock shelter of varying depth. It is divided by walls into a dozen adjacent cave rooms, with the smaller ones at the bottom serving as living quarters for monks. Towards the top, the forest opens up, and the stairway ends at about two-thirds height of the rock. You stand on a terrace in front of the rock niches and have a wide view of the densely wooded plain to the east on the other side. Part of the terrace is of natural origin, but it was artificially extended to create a broader forecourt in front of the largest caves, which served as cult rooms. The walls supporting these terraces on the slope side are ancient. Also, three depressions were carved into the rock in this terrace area for collecting water. The largest basin at the upper end of the terrace measures 3.60 meters by 4.60 meters and surely served as a "Pokuna," a bathing facility for the monks. The smaller ones may have been cisterns for collecting drinking water.

Reclining Buddha of Pidurangala Rock

The most prominent object on this terrace - and the cultural main attraction of Pidurangala - is undoubtedly the 12.5-meter-long figure of a reclining Buddha in the largest of the cave cells (photo). It is not carved from the rock but consists of bricks with mortar joints. It is one of the largest brick representations of a reclining Buddha globally. In Pidurangala, it is said, of course: This is the largest.

The reclining Buddha (photo) gazes to the southeast and was once, when the forest had not yet grown so high again, easily visible from the rock palace of Sigiriya, so that King Kassapa could worship it from there, as it is told.

However, it’s more likely that it was not visible from Sigiriya but was then inside an image house, enclosed by a wall. Side walls are clearly visible, for example, at the feet of the Buddha (photo). Foundations of walls are visible towards the front, indicating that it was probably a closed room. Today, the Buddha lies outdoors under the overhanging rock, giving it the charm of a significant work of art in the jungle. Indeed, this is one of the most pleasant and impressive places to linger on a study trip through ancient Sri Lanka. The figure looks most beautiful in the early morning hours. Only before eight o'clock do the sun rays reach its face.

for more detailed information about the recling Buddha of Pidurangala click here...

Something else might have prevented Kassapa from ever seeing it from his residence in Sigiriya: it might not have existed during his time. The Pidurangala Buddha is often dated to the late Anuradhapura period, around the ninth century. This is because most of the monumental sculptures of ancient Sri Lanka are believed to have originated during this period. Additionally, the capitals of the image house exhibit stylistic features from the even later Polonnaruwa period. However, archaeologists disagree on the dating of the image house and the Buddha. Evidence supporting Kassapa's time includes the fact that the terrace was abandoned and left to decay already in the century following his reign. Ceramics from later centuries were not found here, and the masonry around the statue dates back to Kassapa's time, as confirmed by pottery shard findings, that can be compared with ceramics from Anuradhapura and Sigiriya. It would be surprising if an image house did not already contain a significant statue before its decline. Furthermore, it is important to note that this statue is constructed, not carved from the rock like the monumental statues of the late Anuradhapura period. According to the chief monk of the Pidurangala monastery, the attribution of the reclining Buddha to Kassapa's reign is even inscribed.

In 1988 and 1989, with the permission of the relevant Dambulla monastery, excavations were carried out in the long rock niche with many walled rooms and on the terraces in front of them. The research was carried out in collaboration between local and German archaeologists. Some results are noteworthy. The overall good preservation of the walls and the Buddha figure in the long-unused cave rooms is attributed to the ancient drip ledges that prevented water ingress. Otherwise, the masonry under the rock would have been much wetter, and moss and other plants would have further destroyed the structure. In the uppermost walled rock niche (No.1), no shards of bowls were found, as expected in a monk's cell, but only shards of jugs. Fragments of roof tiles were also discovered, confirming the enclosed nature of the rooms.

From the seventh century onwards, the image house with the reclining Buddha (No.5) was somewhat revered and maintained even after the site's decline, at least to the extent of keeping it free from debris. The figurative decoration on the capitals of this image house likely dates from the Polonnaruwa period, as mentioned earlier. The back of the large reclining Buddha, constructed with mud mortar, does not lean directly against the rock but against a rear brick wall. The Buddha lies on a stepped brick platform and has two layers of stucco: the lower layer is coarser and thicker. The finer stucco of the outer covering was used to model the folds of the garment. Traces of colour were found on the stucco of the pillow and on the soles of the feet, indicating an original painting of the entire figure. The pillow itself was in two parts, with a much smaller first pillow then walled around to create a larger one.

In a corridor between the Buddha's head and the wall of the image house, representations of his curls were found, with each curl as a small terracotta disc. Most of these curls were decorated with a spiral pattern. The head and chest of the wonderful statue were broken open by treasure hunters in the early 20th century. Although it has been restored afterwards, its stucco covering has not been replaced. Therefore, the Buddha is now covered with white stucco only from the feet to the waist.

The vessel types found in the image house could be dated to the fifth to sixth centuries, and after that, the image house and terrace were no longer ritually used, as mentioned above. The side walls of the image house still show clear remnants of decorative elements with pilasters and niches. On the outer wall of the left side, the multiple capitals of the pilasters are still clearly visible. They carried a projecting cornice. The pilasters on the right wall at the Buddha's feet have lost their capital ornamentation, but a larger section of the wall has been preserved, which also features a blind arcade, that is, a niche with pilasters at the edges and an upper arched finish, a kind of false door.

To the right of the image house was another room (No.6), which was probably also used for worship and not, like the other cave rooms, for residential purposes. That's why this room is also called the "small image house." In deeper layers, shards from the fourth century were found here, either predating Sigiriya of from the time when the construction of Sigiriya had just begun. Hair curls of the Buddha from the larger adjoining room were also found here, indicating the use of the small image house when the Buddha statue in the large image house next door had already decayed. The cave of the small image house bears an inscription stating that a mason named Doleganuya donated rice seed to the temple. The mention of ordinary instead of only noble laypeople as donors in inscriptions is a characteristic of inscriptions from the middle Anuradhapura period. Traces of a painting representing a dancer were found on the wall of the small ritual room. Both the interior and exterior walls of the image houses had a painted stucco covering.

In 1988 and 1989, with the permission of the relevant Dambulla monastery, excavations were carried out in the long rock niche with many walled rooms and on the terraces in front of them. The research was carried out in collaboration between local and German archaeologists. Some results are noteworthy. The overall good preservation of the walls and the Buddha figure in the long-unused cave rooms is attributed to the ancient drip ledges that prevented water ingress. Otherwise, the masonry under the rock would have been much wetter, and moss and other plants would have further destroyed the structure. In the uppermost walled rock niche (No.1), no shards of bowls were found, as expected in a monk's cell, but only shards of jugs. Fragments of roof tiles were also discovered, confirming the enclosed nature of the rooms.

From the seventh century onwards, the image house with the reclining Buddha (No.5) was somewhat revered and maintained even after the site's decline, at least to the extent of keeping it free from debris. The figurative decoration on the capitals of this image house likely dates from the Polonnaruwa period, as mentioned earlier. The back of the large reclining Buddha, constructed with mud mortar, does not lean directly against the rock but against a rear brick wall. The Buddha lies on a stepped brick platform and has two layers of stucco: the lower layer is coarser and thicker. The finer stucco of the outer covering was used to model the folds of the garment. Traces of colour were found on the stucco of the pillow and on the soles of the feet, indicating an original painting of the entire figure. The pillow itself was in two parts, with a much smaller first pillow then walled around to create a larger one.

In a corridor between the Buddha's head and the wall of the image house, representations of his curls were found, with each curl as a small terracotta disc. Most of these curls were decorated with a spiral pattern. The head and chest of the wonderful statue were broken open by treasure hunters in the early 20th century. Although it has been restored afterwards, its stucco covering has not been replaced. Therefore, the Buddha is now covered with white stucco only from the feet to the waist.

The vessel types found in the image house could be dated to the fifth to sixth centuries, and after that, the image house and terrace were no longer ritually used, as mentioned above. The side walls of the image house still show clear remnants of decorative elements with pilasters and niches. On the outer wall of the left side, the multiple capitals of the pilasters are still clearly visible. They carried a projecting cornice. The pilasters on the right wall at the Buddha's feet have lost their capital ornamentation, but a larger section of the wall has been preserved, which also features a blind arcade, that is, a niche with pilasters at the edges and an upper arched finish, a kind of false door.

To the right of the image house was another room (No.6), which was probably also used for worship and not, like the other cave rooms, for residential purposes. That's why this room is also called the "small image house." In deeper layers, shards from the fourth century were found here, either predating Sigiriya of from the time when the construction of Sigiriya had just begun. Hair curls of the Buddha from the larger adjoining room were also found here, indicating the use of the small image house when the Buddha statue in the large image house next door had already decayed. The cave of the small image house bears an inscription stating that a mason named Doleganuya donated rice seed to the temple. The mention of ordinary instead of only noble laypeople as donors in inscriptions is a characteristic of inscriptions from the middle Anuradhapura period. Traces of a painting representing a dancer were found on the wall of the small ritual room. Both the interior and exterior walls of the image houses had a painted stucco covering.

Prehistoric Caves of Pidurangala Rock

In the lower caves, those beside the said stairway, prehistoric tools were found alongside pottery, interestingly the same layers contained artifacts made of iron and others of bone. This remarkable coexistence of Stone Age and Iron Age tools has also been found elsewhere in Sri Lanka, too: in Pomparippu on the northwest coast, both types of tools were found together in the same grave and dated to the second or first century BCE. The findings in Pidurangala thus confirm an even older theory about two peculiarities of Sri Lanka's prehistory: firstly, the island did not have a Bronze Age. Instead, the Iron Age followed directly after the Stone Age, and then the historically documented historical period followed soon afterwards.

for a little bit more information about the prehistoric period click here...

This aligns well with the legends of the Sinhalese, who, due to their North Indian Indo-European language, tell of their origin: their ancestors migrated from North India to Sri Lanka by sea and found only a hunter-gatherer culture there. And within a few generations, they adopted writing and religion from the North Indian Emperor Ashoka. Unlike India, Sri Lanka underwent a very abrupt development from the Stone Age to a high culture. This can only be explained by external influences, as implied in the Sinhalese origin legend.

What the excavation finds in Pidurangala directly demonstrate is the second peculiarity of the development of Sinhalese high culture: the Iron Age culture of the immigrants did not displace the Stone Age hunter-gatherer culture from its midst but coexisted side by side. The indigenous people, mostly identified with the present-day Wedda population, retained their cultural techniques, but at the same time, they occupied the same locations as their new neighbours, who introduced a more advanced culture. In fact, the Weddas were still producing the same type of bone artifacts from Paleolithic times, which were found in excavations in the 19th century. The Weddas likely visited the caves of Pidurangala on their hunts long before Pidurangala became a monastery. But what is remarkable is that they remained present here even during Buddhist times.

What the excavation finds in Pidurangala directly demonstrate is the second peculiarity of the development of Sinhalese high culture: the Iron Age culture of the immigrants did not displace the Stone Age hunter-gatherer culture from its midst but coexisted side by side. The indigenous people, mostly identified with the present-day Wedda population, retained their cultural techniques, but at the same time, they occupied the same locations as their new neighbours, who introduced a more advanced culture. In fact, the Weddas were still producing the same type of bone artifacts from Paleolithic times, which were found in excavations in the 19th century. The Weddas likely visited the caves of Pidurangala on their hunts long before Pidurangala became a monastery. But what is remarkable is that they remained present here even during Buddhist times.

Summit of Pidurangala Rock

As said, the well-built forest path ends at the terraces in front of the reclining Buddha. Behind the rock cistern, a small footpath continues to the top of the rock, where the foundations of two stupas are still present. One does not need to be a mountaineerer to ascend to the summit. However, this last third of the ascent cannot be accomplished without using hands and being very careful not to break a foot in one of the many rock crevices (photo). It is best not to climb steeply uphill for the last part but rather to crawl under the huge rock boulder. On the other side, you can then continue very comfortably.

The somewhat adventurous ascent is highly recommended for ordinary hikers, especially for the panorama that unfolds from the summit (the photo shows the view towards the mountainous region).

To the south lies the neighboring rock Sigiriya (photo). To the west, one looks over the flat center of the cultural triangle towards the area of the Kalawewa reservoir.

In the northeast, the view extends towards the region of Anuradhapura (photo). In the north, one can see the mountains of Ritigala. And in the east, the elongated hills near the large tanks of Minneriya and Giritale limit the field of view.

Located close to Sigiriya, the summit plateau of Pidurangala has an advantage for the holiday traveler, which can only be fully appreciated on the spot: the Pidurangala plateau is mostly devoid of people (photo). Though more and more travelers visit this summit, one can still enjoy one of the most breathtaking spots in Sri Lanka often in silence, apart from the strong wind that usually blows up here. A stay on the Pidurangala plateau will undoubtedly leave an unforgettable impression on travelers, no matter how much of the world they may have already seen.

Pidurangala Stupa and Ruins in the plains

Photo 9.1.14 - 13 Pidurangala excavation

Back at the new monastery at the foot of the rock, one should go to the thicket on the other side of the road, just to the north, as there are the remains of the main buildings of the monastery in the forest (photo), which perhaps date back to Kassapa. In total, the monastery, with the residential and meditation facilities on the rock and the ritual center here in the plain, covered an area of over 5 hectares.

Back at the new monastery at the foot of the rock, one should go to the thicket on the other side of the road, just to the north, as there are the remains of the main buildings of the monastery in the forest (photo), which perhaps date back to Kassapa. In total, the monastery, with the residential and meditation facilities on the rock and the ritual center here in the plain, covered an area of over 5 hectares.

The ceremonial buildings of the ancient monastery are arranged like a Pabbata Vihara of the late Anuradhapura period, except that they do not lie elevated on a common platform. There is a striking similarity to the Pabbata Vihara of Menikdena, with the exception that the stupa and Bodhighara (the latter in the foreground of the photo) are arranged in reverse.

The brick stupa (photo) on a wide and relatively high terrace of its own is surrounded by originally 16 Asanas, stone thrones symbolizing the presence of a Buddha. The stupa is said to have been erected at the spot where the cremation of King Kassapa took place. In fact, organic remains found here were dated back to the fifth century.

In the relic chamber of this stupa, three relief plates were found in 1951 by no less than Senarath Paranavithana, Sri Lanka’s leading archaeologist in the mid 20th century. The tablets were made of limestone not otherwise used in Sri Lanka. They are most likely import pieces from India, from the time of Kassapa I, in the late 5th century. These reliefs, now kept in the Archaeological Museum of Anuradhapura, are original pieces of Amaravati art, located in the area of today's southern Andhra Pradesh, which was stylistically very influential for the art of Sri Lanka.

In the relic chamber of this stupa, three relief plates were found in 1951 by no less than Senarath Paranavithana, Sri Lanka’s leading archaeologist in the mid 20th century. The tablets were made of limestone not otherwise used in Sri Lanka. They are most likely import pieces from India, from the time of Kassapa I, in the late 5th century. These reliefs, now kept in the Archaeological Museum of Anuradhapura, are original pieces of Amaravati art, located in the area of today's southern Andhra Pradesh, which was stylistically very influential for the art of Sri Lanka.

As in Menikdena, at the back of the area, there is a picture house on the left and, for the highest ceremonies, an Uposathaghara (photo) on the right, which is noticeable for its particularly powerful stone pillars.

Also entirely analogous to Menikdena, in the middle of the four classical main buildings of a Pabbata Vihara, there is an additional fifth one, namely a Sannipata-Salawa (also called Saba-Salawa) for the daily gatherings of the monks.

This five-part ensemble corresponds to the classical so-called Panchamasa concept of Buddhist monastery architecture in Sri Lanka, which, in addition to the monks' residences, natural caves or huts made of perishable organic material, includes five central ritual sites made of stone. "Panch" means "five" in many Indian languages. In addition to the two halls for ordination ceremonies or daily gatherings, these core buildings of a monastic complex also include shrines visited by laypeople for the worship of a Bodhi tree, a relic in the stupa, and a Buddha statue.

Also entirely analogous to Menikdena, in the middle of the four classical main buildings of a Pabbata Vihara, there is an additional fifth one, namely a Sannipata-Salawa (also called Saba-Salawa) for the daily gatherings of the monks.

This five-part ensemble corresponds to the classical so-called Panchamasa concept of Buddhist monastery architecture in Sri Lanka, which, in addition to the monks' residences, natural caves or huts made of perishable organic material, includes five central ritual sites made of stone. "Panch" means "five" in many Indian languages. In addition to the two halls for ordination ceremonies or daily gatherings, these core buildings of a monastic complex also include shrines visited by laypeople for the worship of a Bodhi tree, a relic in the stupa, and a Buddha statue.

Inscriptions (photo) from the middle Anuradhapura period on the steps of the image house and the assembly hall remind that some patrons of this monastery accumulated additional merits by buying slaves' freedom. The word for these servants is "Vahallu," related to our word "vassal." After them, one donor text is also called Vaharala inscription. It is written in a late form of Brahmi letters and reflects a very ancient Sinhala.

|

The text reads:

"Some individuals from various places like Mahagala and Bulabala donated Ahavanus and Amunas from paddy fields to the Dalha Vihara and thereby released many slaves. May the merit gained from this benefit all beings." |

Finally, it should be noted that halfway from Pidurangala to Sigiriya, there is a particularly quaint specimen of a Banyan tree.