Lankatilaka, in 18 km distance from Kandy by road, is the largest and most picturesque of the three so-called Western Temples. The main attraction is the most beautiful shrine room from the Kandy period, with various excellent paintings from the 18th century. However, the temple structure is from the Gampola period in the 14th century. One typical feature of temples from the late Middle Ages is an architectural concept integrating Hindu shrines into a mainly Buddhist sanctuary. Due to its quite scenic location on the back of a gneiss hill, the Lankatilaka Vihara is also known as "temple on the rock".

|

Content of our Lankatilaka page: location - ancient stairway - inscription - architecture - Antarala - Buddhist main shrine - Kandy paintings - Devales for the gods - 5 Hindu deities accommodation digressions: Bhuvenaikabahu IV - Gampola period Buddhism - Arhats - Solosmasthana - Suvisi-Vivarana - Sat-Sati - Satara-Varam-Deviyo - religious politics |

The name “Lankatilaka” means “Lanka’s adornment” or “Island’s ornament”. “Tilaka” originally means “sign, mark, icon”. In Hinduism, the tilaka is the mark worn on the forehead. The common name “tika” for this third eye is an abbreviation of “tilaka”. Lankatilaka is pronounced “Lunke-Tileke”, the third syllable, “ti”, is stressed and short. The second, the last and the second last syllable is not stressed and their vowel “a” is spoken as a short “e” like in “egg”, this means, neither as an English nor a Latin “a”. Lankatilaka is also the name of the largest image house from the Polonnaruwa period. That other Lankatilaka monument, built 200 years earlier and belonging to the main monastery of Polonnaruwa, Alahena Pirivena, is now in ruins and not restored, whereas the Gampola-period Lankatilaka shrine near Kandy is still intact and roofed. |

Location of Lankatilaka Viharaya

|

The Lankatilake temple, officially named Sri Lankathilaka Rajamaha Viharaya, is located 18 km to the southwest of Kandy and 15 km to the north of Gampola. The two other Western Temples, Embekke and Gadaladeniya, are both in 4 km distance, to the south and north respectively. Lankatilaka is situated on a rock called “Panhalgala” in the village of Rabbegamuwa in the Udunuwara division of Kandy District. The easiest way to reach Lankatilaka is to take the Kandy-Colombo main road (A1) to Pilimatalawa and there take the B116 to the south, along Gadaladeniya.

|

Access to the Panhalgala Hill and its temple complex

Rabbegumawa, situated on the hills to the west of the Lankatilaka Vihara, was once a typical temple village, viz. a settlement area of temple servants. Labour service was common at Sri Lanka’s ancient monasteries, because monks were not allowed to work or cook. Temple labours were part of the feudal system of the Kandy kingdom.

Two flights of steps, about 50 m long, were cut into the rock to allow climb from the foot of the Panhalgala hill. The ancient stairways are on the side of the nearby village of Hiyarapitiya in the plains. The weathered 172 steps are the original stairway built in the Gampola era. An additional one was carved out from the rock in 1913. This steep access is mentioned in the travelogue of the German poet Hermann Hesse.

Two flights of steps, about 50 m long, were cut into the rock to allow climb from the foot of the Panhalgala hill. The ancient stairways are on the side of the nearby village of Hiyarapitiya in the plains. The weathered 172 steps are the original stairway built in the Gampola era. An additional one was carved out from the rock in 1913. This steep access is mentioned in the travelogue of the German poet Hermann Hesse.

Besides the large image house which is the main temple, there are some other buildings in the premises of Lankatilaka Vihara, namely a stupa and a Bo-tree in the northwestern corner of the temple premises on the rocky hill, just to the left behind the main gate. Buddha footprints called Siripatula can also be found near the tree. The monks’ dwellings are in the southwestern corner of the Panhalgala rock. This residential area is not open to the public. A preaching hall is situated at the eastern slope, where the stairway enters the temple compound in front of the main temple. A remarkable feature are the patterns of the tiles. Similar roof decorations can also be seen in Embekke.

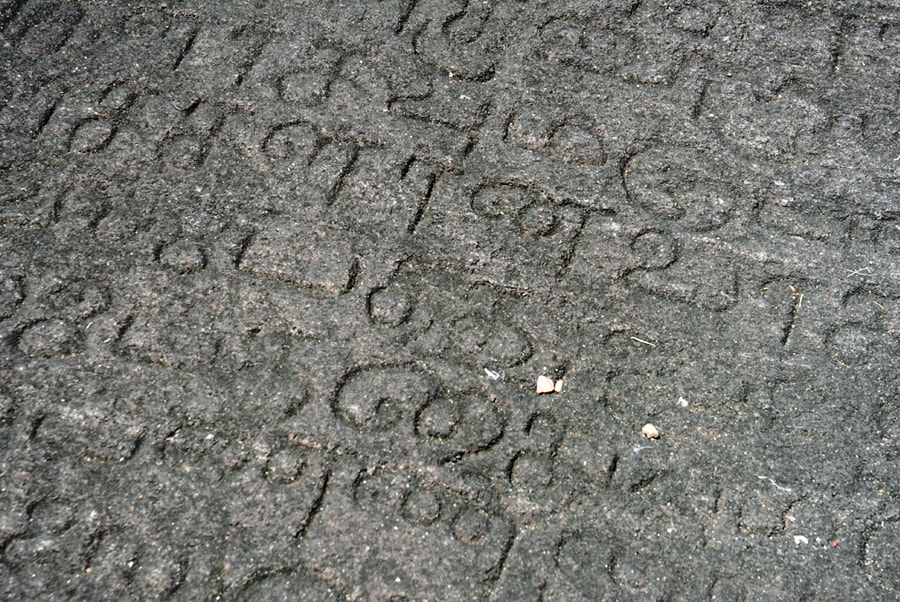

Lankatilaka inscription

Lankatilaka is the most important monument from the Gampola period (mid and late 14 century). On the other hand, the large rock inscription named Shila Lekhana that can be seen on the solid rock surface at the southwestern side of the temple building, is the most significant historical source concerning the beginnings of the Gampola in the mid 14th century.

The Shila Lekhana inscription of Lankatilaka gives the date of the year 1266 of the Indian Shaka calendar, which corresponds to 1344 A.D. It’s a typical donation inscription mentioning that land was gifted by the kingdom and what provisions were taken to maintain the temple. However, there are several remarkable aspects of this inscription. Firstly, it contains both Sinhala and Tamil sections and it mentions Sinhalese and Tamil troops of the royal army. An important role of Tamil mercenaries in the royal army of Sri Lankan kings had been common since the mid Anuradhapura period. Tamil soldiers as guardians of major Buddhist temples are known from the Polonnaruwa period. But what’s new in the Gampola period is that a mixed army is mentioned as protecting the mixed Buddhist and Hindu temple and, even more remarkable, that regulations refer to castes. This is one prove of increasing Hindu influence in the Sinhala form of Buddhist religion. Secondly, what is even more remarkable is that this greatest temple of the Gampola kingdom is not a royal donation but that of a minister and general named Senalankadhikara, “Sena Lanka Adhikara” translates to “Army-general Lanka nobleman”. In Sanskrit, “adhikara” literally means “authority and ownership.” The chief minister Senalankadhikara is mentioned in a poem from the Gampola period named Thisara Sandeshaya, which translates to “swan’s message”. It’s a about a journey of a swan to the gods. The fable mentions that Senalankadhikara donated a temple to deities, hoping that the merit earned by this pious deed will help him to attain Buddhahood in a later life. This means, his ambition is to be a Bodhisattva. Furthermore, he is credited with the 10 Paramitas, which are the virtues of Bodhisattvas in classical Mahayana Buddhist Sutras, proving the influence of Mahayana doctrines on literature of the Gampola kingdom. Prior to the Gampola period, only Sri Lankan kings were sometimes considered Bodhisattvas or future Buddhas. The elevation of a nobleman to this high religious status indicates the weakness of the kingdom at this point in time. Thirdly, the Lankatilaka rock inscription is the earliest source in Sri Lanka mentioning Natha, literally meaning "lord" or "protector", side by side with Maitri (known as Maitreya in Sanskrit and Metteya in Pali) as a Bodhisattva. Maitri, the future Buddha, is a Bodhisattva known from the Theravada Buddhist tradition. But Natha, identified with Lokeshvara alias Avalokiteshvara in other Gampola-period inscriptions, is the most significant saviour-Bodhisattva in Mahayana Buddhism. This indicates a blend not only of Buddhist and Hindu elements at this Buddhist temple of Lankatilaka but also Mahayana influences. Natha, originally a local deity venerated in Kandy, will play an increasingly important role in Sinhala Buddhism. He will become one of the four major Sinhalese gods in the Kandy period. However, in the Gampola kingdom, Natha Lokeshwara and Maitri seem to be intermediates between Buddha and gods according to the inscriptions from this late medieval period. Forty years later on, Natha is considered a deity supporting the Alagakonnara family, then related by marriage with the Gampola kings. The victories of the Alagakonnaras over armies of the Jaffna kings are attributed to advice of Natha, who speaks to them in their dreams. |

Period of Bhuvanaikabahu IVThe construction of the Lankatilaka Vihara took place during the reign of King Bhuvenaikabahu IV (1344-52), who was the first monarch who chose Gampola, then known as Gangasiriripura, as his residence. Bhuvenaikabahu VI was a weak ruler. There were at least 5 other power centres during his reign. Firstly, his chief minister and general Senalankhadikhara, the founder of the Lankatilaka Vihara, seems to have played a more decisive role in Gampola than the king. Secondly, there was another powerful family, which later on came to the position of head of government and finally kings, the Algakonaras of Southindian origin. During the period of Bhuvenaikabahu IV, a "Konnar" Alagakonaras already were in a high position in Kurunegala, as is reported by Ibn Batuta, the famous Arab traveller. Kurunegala was the former capital, it is likely that the royal family went to Gampola due to the predominance of the Alagakonaras in Kurunegala. Thirdly, there was another Sinhalese king, a co-regent, during the reign of Bhuvenaikabahu IV. Parakramabhu V, suposedly his brother, had his residence in Dedigama, in only 35 km distance from Gampola, as the crow flies. Parakramabahu became Bhuvenaikabahu's successor in Gampola later on. Fourthly, there was a stronger realm on the island in this period. Invading armies of the Tamil kings of Jaffna managed to forced their southern Sinhalese neighbours to pay duties. This happened at the end of Bhuvenaikabahu's or at the begin of his sucessor's reign in Gampola. It was the Alagakonara family mentioned above that later on managed to repulse the invaders from the northern parts of the island. Gampola-period BuddhismIn spite of Mahayanist and Brahmanist tendencies, the development of religious ideas in the Gampola period is not a turning away from the island nation’s Theravada Buddhist tradition. The religion’s supreme being, the Buddha, is not interpreted in a Mahayanistic manner. Neither does the Buddha or Buddhahood become a kind of primordial principle nor a universal saviour rewarding just believing faith and trust in him. On the other hand, he is not in the least degraded to a shady manifestation of Vishnu as in orthodox Hinduism. Rather, the religious vision of the Buddha, to whom alone all highest honors remain to be reserved, continues to be the classic Theravada-Buddhist concept of a being overcoming all worldly things through own insight and awareness and cognition. Thereby, the concept of redemption remains to be in accordance with Theravada-Buddhist teachings. There is no belief in redemption as transmittable or in substitution for the sake of others, as in Christianity and also in Mahayanism. There is solely the way of finding the same path to salvation as the Buddha, with the help of such a highly rational and effective teacher. He is not beleived to affect the world and the course of events in any other way. In the Gampola period, that highest position of the Buddha as the universal master of spiritual knowledge did not change, although the Bodhisattva virtues of loving care played a more prominent role in the doctrines than previously. Even so, the Buddhist order, the Sangha, is not at all neglected in favour of other religious institutions. Just in this period, there were two major religious reforms aiming to strengthen the traditional Theravada, the second one was performed by one of the members of the Alagakonnara family. |

Following Buwanekabahu IV, five consecutive kings chose Gampola as their residence. The tooth relic was transferred drom Kurunegala to Gampola during the reign of Bhuvenaikabahu's son, Vikramabahu III (1357-74). However, the centre of power shifted to Kotte near Colombo. Kotte was founded and fortified and chosen as residence by the Alagakonnara lineage. Although the Sinhalese kings in Gampola were not powerful monarchs, their period has made significant contributions to art and literature of Sri Lanka, the Lankatilaka Vihara being the most impressive manifestation.

Architecture of Lankatilaka Viharaya

"Blue Temple" Lankatilaka in the year 2000

"Blue Temple" Lankatilaka in the year 2000

Lankatilaka one once known as the “Blue Temple”, due to its bluish coat of paint. The new paint is white.

The horizontal ground plan as well as the storey architecture of the Lankatilaka temple are quite remarkable. Both the horizontal layout and the vertical outline could be the result of refurbishments throughout the centuries. Surprisingly, this yielded a harmonious overall look.

Originally, the Lankatilaka temple was designed by an architect from southern India, Sathapati Rayar. In essence, the architecture is patterned after Gedige type of the Buddhist architecture from the Polonnaruwa period, which in turn mirrored Hindu temples of India, with a Garbhagriha room for the idol below the Sikhara temple tower and an adjacent Mandapa hall for visitors to the east. Buddhist images houses, of course, replace the idol of a Hindu deity by a Buddha statue. Image houses are called Pathimagara in the ritual language Pali or Pilimage in modern Sinhala. Gedige in a narrow sense is the brick vault roofing over a Buddhist image house. But the term Gedige can apply to image houses in general, too. Already in the Anuradhapura period, Gediges had been constructed for worshipping Buddha images. It was during the Polonnaruwa period that they became large-sized buildings playing a dominant role in temple architecture.

The Gedige of Lankatilaka near Kandy is unique, as it is not constructed on flat ground but on a sloping and uneven surface of a natural rock. The 30 m long temple structure has a granite foundation and walls of the inner shrine room are partly built of stone, the outer walls are made of brick. Both kinds of walls got a a lime plaster covering.

Apart from foundations and door jambs, Lankatilaka is an overall brick construction. Brick was the preferred material of traditional sacral architecture in Sri Lanka. Traditionally, stone was only used for pillars and window and door frames as in the case of Lankatilaka. In contrast, Dravidian Hindu temples in southern India are usually stone monuments. The use of granite instead of bricks for temple walls in the case of the contemporary Gadaladeniya temple is result of Southindian architectural influence.

The temple has an inner wall of the central Budhist shrine room and an outer wall of coronol annexes for auxiliary Hindu shrines of much smaller size. It is not entirely clear, whether this onionskin-layout was the original groundplan. It seems more likely, that only the inner walls are from the Gampola period, constructed according to the plans of the Indian architect Sathapati Rayar. The outer brick walls creating the said ring of Hindu chapels is a later addition in this case. On the other hand, the tiered structure of the tiled roofs is presumed to be from the Gampola period according to some art historians. In this case, it is more likely, though not absolutely neccesary that the ground floor was wider than than the first upper floor. This article - without claiming any expertise to be able to verify it - prefers the theory that the outer ring and the current tiered structure of the roof is a result of refurbishments of the Kandy period, see below. Definitely, the interior was extensively altered during the 18th century.

According to a copper plaque inscription found in Lankatilaka, the original temple was construct as a four-storied mansion with a height of more than 25 meters. However, the outline has changed significantly, if the hypothesis of later refurbishments is correct. Today, only 3 stories can be seen from the outside. There is only one upper floor inside the building, the stairway to this one upper storey is behind the central statue. A second upper level, not existing any more, is said to have contained a reclining Buddha, presumably of small size. The highest storey sheltered scriptures and relics. But what is called “storey” particularly in Dravidian Indian temple architecture, is usually referring to layers or tiers of the roof, not to man-size rooms. “Storeys” in that respect can be of less than one meter in height. Typically, Dravidian temple roofs consisted of three layers of decreasing sizes. Thereby, the a roof was shaped like a step-pyramid, crowned by a small dome called Stupika. This kind of outline is still intact at the nearby Gadaladeniya temple.

The horizontal ground plan as well as the storey architecture of the Lankatilaka temple are quite remarkable. Both the horizontal layout and the vertical outline could be the result of refurbishments throughout the centuries. Surprisingly, this yielded a harmonious overall look.

Originally, the Lankatilaka temple was designed by an architect from southern India, Sathapati Rayar. In essence, the architecture is patterned after Gedige type of the Buddhist architecture from the Polonnaruwa period, which in turn mirrored Hindu temples of India, with a Garbhagriha room for the idol below the Sikhara temple tower and an adjacent Mandapa hall for visitors to the east. Buddhist images houses, of course, replace the idol of a Hindu deity by a Buddha statue. Image houses are called Pathimagara in the ritual language Pali or Pilimage in modern Sinhala. Gedige in a narrow sense is the brick vault roofing over a Buddhist image house. But the term Gedige can apply to image houses in general, too. Already in the Anuradhapura period, Gediges had been constructed for worshipping Buddha images. It was during the Polonnaruwa period that they became large-sized buildings playing a dominant role in temple architecture.

The Gedige of Lankatilaka near Kandy is unique, as it is not constructed on flat ground but on a sloping and uneven surface of a natural rock. The 30 m long temple structure has a granite foundation and walls of the inner shrine room are partly built of stone, the outer walls are made of brick. Both kinds of walls got a a lime plaster covering.

Apart from foundations and door jambs, Lankatilaka is an overall brick construction. Brick was the preferred material of traditional sacral architecture in Sri Lanka. Traditionally, stone was only used for pillars and window and door frames as in the case of Lankatilaka. In contrast, Dravidian Hindu temples in southern India are usually stone monuments. The use of granite instead of bricks for temple walls in the case of the contemporary Gadaladeniya temple is result of Southindian architectural influence.

The temple has an inner wall of the central Budhist shrine room and an outer wall of coronol annexes for auxiliary Hindu shrines of much smaller size. It is not entirely clear, whether this onionskin-layout was the original groundplan. It seems more likely, that only the inner walls are from the Gampola period, constructed according to the plans of the Indian architect Sathapati Rayar. The outer brick walls creating the said ring of Hindu chapels is a later addition in this case. On the other hand, the tiered structure of the tiled roofs is presumed to be from the Gampola period according to some art historians. In this case, it is more likely, though not absolutely neccesary that the ground floor was wider than than the first upper floor. This article - without claiming any expertise to be able to verify it - prefers the theory that the outer ring and the current tiered structure of the roof is a result of refurbishments of the Kandy period, see below. Definitely, the interior was extensively altered during the 18th century.

According to a copper plaque inscription found in Lankatilaka, the original temple was construct as a four-storied mansion with a height of more than 25 meters. However, the outline has changed significantly, if the hypothesis of later refurbishments is correct. Today, only 3 stories can be seen from the outside. There is only one upper floor inside the building, the stairway to this one upper storey is behind the central statue. A second upper level, not existing any more, is said to have contained a reclining Buddha, presumably of small size. The highest storey sheltered scriptures and relics. But what is called “storey” particularly in Dravidian Indian temple architecture, is usually referring to layers or tiers of the roof, not to man-size rooms. “Storeys” in that respect can be of less than one meter in height. Typically, Dravidian temple roofs consisted of three layers of decreasing sizes. Thereby, the a roof was shaped like a step-pyramid, crowned by a small dome called Stupika. This kind of outline is still intact at the nearby Gadaladeniya temple.

The original threy-storeyed temple roof collapsed, at least in parts. It could have been a stone roof instead of the current tiled roof. If this assumption (which, it has to be said, is controvertible, see above), is correct, the reason for the rearrangement of the number of tiers is evident: Stone roofs are not appropriate for rainy areas, as they can not be sufficiently sealed up. The inner shrine rooms, containing valuable statues and paintings, get wet and the entire structure can weather quickly and thereby become unstable. That Dravidian type of stone roofs was perfectly well adapted to the dry-zone climate of southeastern India, which is today’s state of Tamil Nadu, where numerous huge Dravidian monuments still exist. However, this kind of architecture or roof construction is not found in the monsoon zone of southwestern India, in today’s state of Kerala. In contrast to Tamil Nadu, many of Kerala's temples are made of wood and have tiled roofs. In Sri Lanka, stone monuments like Nalanda Gedige were constructed in the dry zone, too. But when imitating this Dravidian architecture in the rainy hillcountry, this construction type turned out to be inappropriate. This is why one characteristic feature of the later Kandyan architecture is the tiled roof, similar to those temples in Kerala, though of a slightly different shape. Hence, when the collapsed roof of Lankatilaka was restored, the Kandyan style of roof was chosen, as a more reliable protection of the shrine. Therefore, what can be seen today, is a Gampola-period temple with a Kandy-period roof.

vaulted circumambulatory and original outer walls of Lankatilaka's shrine room

vaulted circumambulatory and original outer walls of Lankatilaka's shrine room

Furthermore, the layout had to be altered, too. The groundplan was enlarged. The original temple consisted of a shrine room. The outer walls had alcoves for sculptures of Hindu deities. However, these images were exposed to more rain than their counterparts in Southeast India. In order to protect them, a roofed ambulatory with an additional outer brick wall was built, surrounding the inner stone shrine room on all sides, except from the eastern entrance. The thick outer walls made of brick are well designed with arches and sculptures. The entire plan of the Lankatilaka temple now protrudes to the four sides like of a cross. The Hindu shrines with sculptures of deities at the cardinal points are protected by separate tiled roofs of the ground floor, whereas main roof on the upper storey only covers the central Buddhist shrine room. Yet the result of the Kandyan refurbishment is a coherent type of architecture, a unique blend of Dravidian and Kandyan elements.

The original Buddhist image house faces to east, whereas the entrance to the vaulted aisles connecting the Hindu shrines is from the west. There is probably no other building in the world integrating Buddhist and Hindu places of worship in such a harmonious and symmetrical way.

The original Buddhist image house faces to east, whereas the entrance to the vaulted aisles connecting the Hindu shrines is from the west. There is probably no other building in the world integrating Buddhist and Hindu places of worship in such a harmonious and symmetrical way.

Antarala - Doorway

Approach to the Buddhist image house, which is the main shrine of the Lankatilaka temple, is from the east. The narthex or front hall of an Indian temple is sometimes called Antarala or Antharalaya. Confusingly, the term Antarala often refers to the narrow joint between the Garbhagriha chamber of the idol and the Mandapa hall in front of it. If Antarala means the inner corridor to the west of the Mandapa, the vestibule with the eastern outer entrance of the Mandapa hall is called Ardhamandapa in Indian architecture, not Antarala. To be clear (or confusingly unclear): What we are discussing now under the headline "Antarala", is such a Ardhamandapa structure, the elongated eastern doorway of the entire shrine.

There is an almost undecorated moonstone or Sandakadapahana in front of the flight of steps below an arched doorway. The arch at the entrance to the Lankatilaka image housenis a simple form of a Makarana Torana, Torana designating the door and Makaras the two crocodile-like creatures framing the arch. The balustrades are monolithic Gajasinha statues. Gajasinha, also transcribed Gajasimha, translates to “elephant-lion”. Gajasinhas are lions represented with elephants’ heads. In Sri Lanka, Gajasinhas replace Makara balustrades in the late Middle Ages. They can already be seen at the stairway of Yapahuwa, which was built one century earlier than Lankatilaka Vihara. In contrast to the Yapahuwa Gajasinhas, the elephant-lions of the Gampola period are depicted with the head and trunk bent to the back. Above the flight of steps, inside the doorway, two large murals depicting lion figures can be seen, a unique feature of the Antarala of Lankatilaka. In front of the main gate to the shrine room. In contrast to most other Davarapalas, they are nit positioned facing east but looking into the hall of the Antarala from the side. They carry swords as weapon. But they don’t look angry. Sri Lankan Dvarapalas are often depicted in a less furious way than their Indian or Southeastasian counterparts.

There is an almost undecorated moonstone or Sandakadapahana in front of the flight of steps below an arched doorway. The arch at the entrance to the Lankatilaka image housenis a simple form of a Makarana Torana, Torana designating the door and Makaras the two crocodile-like creatures framing the arch. The balustrades are monolithic Gajasinha statues. Gajasinha, also transcribed Gajasimha, translates to “elephant-lion”. Gajasinhas are lions represented with elephants’ heads. In Sri Lanka, Gajasinhas replace Makara balustrades in the late Middle Ages. They can already be seen at the stairway of Yapahuwa, which was built one century earlier than Lankatilaka Vihara. In contrast to the Yapahuwa Gajasinhas, the elephant-lions of the Gampola period are depicted with the head and trunk bent to the back. Above the flight of steps, inside the doorway, two large murals depicting lion figures can be seen, a unique feature of the Antarala of Lankatilaka. In front of the main gate to the shrine room. In contrast to most other Davarapalas, they are nit positioned facing east but looking into the hall of the Antarala from the side. They carry swords as weapon. But they don’t look angry. Sri Lankan Dvarapalas are often depicted in a less furious way than their Indian or Southeastasian counterparts.

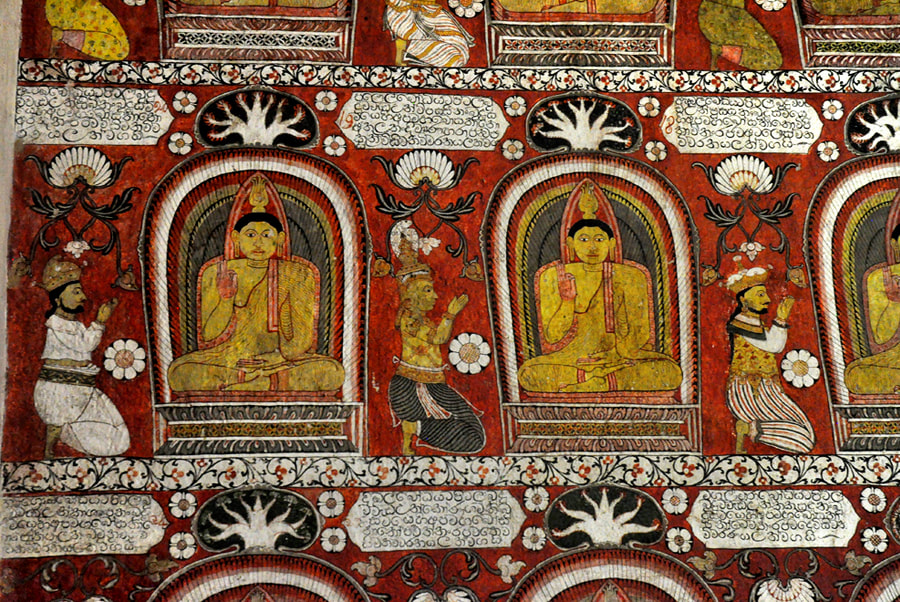

Buddhist shrine of Lankatilaka Vihara

The main shrine room of the Lankatilaka Vihara is a typical image house, decorated with Buddha statues and paintings. As in Indian architecture of Hindu temples, the chamber containing the main idol of the temple is called Garbhagriha, which translated to “uterus house”. The decorations are mostly from the Kandyan period. Compared to prayer rooms of churches or mosques, the shrine room is not large. But it’s much more spacious than Garbhagrihas of Indian temples, access to which is usually permitted only to Brahmin priests. The shrine room of Lankatilaka is open to the public, as it is a combination of Garbhagriha and Mandapa, a Mandapa being the hall for prayers. In Indian temples, both rooms are usually separated by a door. In the case of Lankatilaka, they both form one single room. This is why it is larger than other Garbhagrihas.

The main image of worship is a 4 m tall Seated Buddha statue in Samadhi Mudra, which is the meditation gesture, also known as Dhyani Mudra. The posture of the legs is called Virasana, though it’s not identical with the Yoga posture of the name. Virasana, also known as Paryankasana, is the half-lostus posture. The right leg is folded on top of the left one, without being interlocked as in the case of lotus posture, known as Padmasana. Virasana is by far the most common sitting posture of Buddha images in Sri Lanka and Thailand, in contrast to the north Indian tradition, where a version ot the Padmasana is predominant.

The colossal statue is made of brick and covered with stucco. Presumably, it is from the time of origin of the temple, this is the Gampola period. However, today’s appearance is from the Kandy period, as the scuplture was remodelled and restored and repainted, when King Kirthi Sri Rajasingha reformed the order and reactivated many monasteries that had fallen into decay. Buddha images from the Gampola period, of which some bronze sculptures survived, are without any folds.

The Seated Buddha is framed by a an elaborate Makara Torana and flanked by two standing Buddhas in Vitarka Mudra, which is the the preaching gesture. The undulating folds of the garment are typical of the Kandy period.

The Makara Torana framing the Seated Buddha is impressive. As mentioned, this typical element of Indian architecture framing door arches and sculptures is named after the mythical crocodiles at the side, which are sometimes called dragons. The arches are also called Kala Makara Toranas, Kalas being the demon heads at the top. This demon face, which is also known as Kirthi Mukha, and the Makarara dragons spout out the rank which forms the arch. All elements of the Dragon pandol are symbols of fertility and wellbeing.

Above the Makara Torana framing the Seated Buddha statue's head is a group of sculptures of Hindu deities, venerating or protecting the Buddha:

The colossal statue is made of brick and covered with stucco. Presumably, it is from the time of origin of the temple, this is the Gampola period. However, today’s appearance is from the Kandy period, as the scuplture was remodelled and restored and repainted, when King Kirthi Sri Rajasingha reformed the order and reactivated many monasteries that had fallen into decay. Buddha images from the Gampola period, of which some bronze sculptures survived, are without any folds.

The Seated Buddha is framed by a an elaborate Makara Torana and flanked by two standing Buddhas in Vitarka Mudra, which is the the preaching gesture. The undulating folds of the garment are typical of the Kandy period.

The Makara Torana framing the Seated Buddha is impressive. As mentioned, this typical element of Indian architecture framing door arches and sculptures is named after the mythical crocodiles at the side, which are sometimes called dragons. The arches are also called Kala Makara Toranas, Kalas being the demon heads at the top. This demon face, which is also known as Kirthi Mukha, and the Makarara dragons spout out the rank which forms the arch. All elements of the Dragon pandol are symbols of fertility and wellbeing.

Above the Makara Torana framing the Seated Buddha statue's head is a group of sculptures of Hindu deities, venerating or protecting the Buddha:

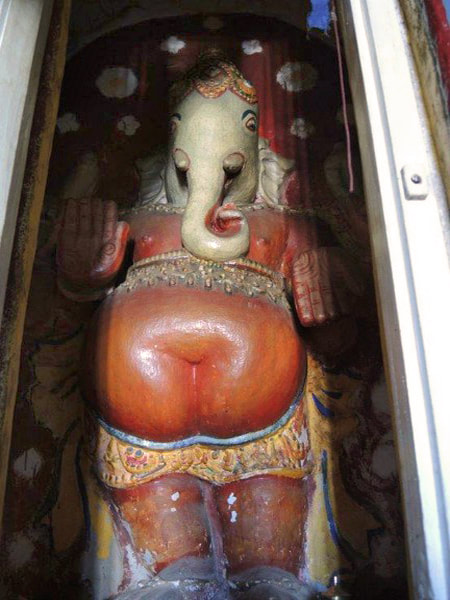

Shiva and his family in a Buddhist shrine

To the left hand side of the Buddha (respectively to the right when you are facing him), Shiva and Parvati can be seen in the corner just below the ceiling. Depictions of Shiva, the supreme god of Tamil Hinduism, are usually a very rare sight in Buddhist shrine of Sri Lanka. In contrast to Vishnu's consort Lakshmi, Shiva's wife Parvati is rarely depicted in Buddhist works of art. The occurrence of these deities indicates the syncretic character of the Lankatilaka shrine, integrating Hindu elements in the Buddhist worship. Below Shiva and Parvati is their elephant-headed son, Ganesha. Ganesha as Ganapati - this is in his function as leader or lord (pati) of the fertility-bringing gnomes (ganas) - is not an uncommon figure in Buddhist art. Ganesha is still worshipped by some Sinhalese Buddhists inhabiting northern parts of Sri Lanka, living among Tamils or close to Tamil majority areas. Here he is known as Pulleyar, the elephant lord of the scrub jungles. The Tamil name of the elephant-headed deity is Pillaiyar. Remarkably, the Sinhalese Pulleyar lacks specific parents and is a servant of the Buddha. In contrast, the Ganesha in the Lankatilaka temple is depicted in Hindu manner, in a group with his parents, who are above him. Their other son, Ganesha's brother, can be seen in the same layer is close to him: The red-faced Skanda, known as Kataragama in Sri Lanka, is half hidden below the Makara Torana. All Hindu gods mentioned above display Anjali Mudra, also known as Namaskara Mudra, having the hands folded in front of the breast, a gesture of adoration for the Buddha.

An Avatar of Vishnu in a Buddhist shrine

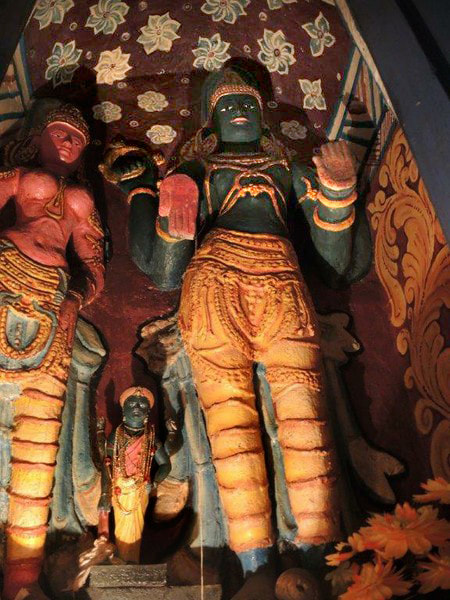

His counterpart on the other side, also half hidden by the dragon arch, is Upulvan. Identified with Vishnu, Upulvan is a highly-venerated deity in traditional Sinhalese Buddhism, interpretet as a protector of the Buddhist teachings and the Buddhist island. According to mythology, Upulvan is blue-faced. But it’s quite common to use any darkish colour in works of art depicting him. Noteworthy is that Vishnu is represented a second time. Close to Upulvan can be seen a figure with the head of a boar. This is Varaha, one of the ten classic Avatars, an incarnation of Vishnu. In contrast to Upulvan, Avatars of Vishnu are rarely seen in Buddhist shrines, except from the Buddha himself, who is considered to be the ninth incarnation of Vishnu. But this is only a belief of Hindus. Buddhists don’t consider the Buddha to be an Avatar. The reason is: In Buddhism, a Buddha is a higher being than a god, whereas an Avatar is not superior to his deity in Hinduism.

The Hindu Trimurti in a Buddhist shrine

Above Upulvan, the local Sinhalese deity, and Varaha, the Hindu Avatar, which both represent Vishnu, is another exceptional mythological figure, namely Brahma. He can be easily identified by his four faces. In general, Brahma is not an uncommon mytholgical figure in Buddhist art. Actually, Brahma is more venerated in Buddhism than in Hinduism, as a leading deity, regarded as the heavenly king and supreme protector of the Buddhist teachings, a so-called Dharmapala, doctrine-guardian. According to Buddhist traditions, it was Brahma who appeared before the Buddha urging him to teach others instead of being satisfied with finding enlightenment only for himself. Despite this important role of Brahma in Buddhism, there is a major difference to Hindu teachings about Brahma: In Buddhist art, Brahma is never depicted as a creator. Again, there is something extraordinary in the depiction of Brahma in the Lankatilaka shrine room. Here he is seen in a group with Shiva and Vishnu. This means, the Hindu trinity of supreme divinity, the famous the Trimurti, is represented in the Buddhist shrine of Lankatilaka. But they are not depicted as supreme beings. Rather, they are obviously degraded to protectors of the Buddha, among other guardian figures.

Hindu Devales of Lankatilaka

southern Devale and corridor of Lankatilaka's outer ring of 5 such shrines

southern Devale and corridor of Lankatilaka's outer ring of 5 such shrines

As mentioned, the Lankatilaka Temple has an outer ring of shrines for Hindu deities, which can be appoached from the western side, whereas the entrance to the main shrine for Lord Buddha is facing east. In front of the western entrance to the Hindu shrines is a small hall, partly open at breast height. It serves as a so-called Digge, “Dig-Ge” translates to “drumming house”. It’s a hall for music performances.

Those shrines of Hindu deities venerated also by Sinhalese Buddhists are called Devales, whereas Kovils are shrines of Tamil Hindus. Hidden behind curtains, the idols of the Devales are placed in niches of what was once the outer wall of the original Gampola-period temple building and is still the exterior wall of the central Buddhist shrine room. Each of the five Devales of the Lankatilaka has its own entrance, but four of the doors are almost always closed. The western door is sometimes opened or a key can be arranged by temple servants. As all five Devales are connected by a joint vestibule, all five statues of the Hindu gods can be visited from the western entrance. The corridors are quite narrow and have asymmetric barrel-vaulted roofs, leaning against the inner wall. This construction type quite typical for ambulatories of temples from earlier periods, too. Thus, it would come to no surprise, if this ring of aisles would be from the late medieval Gampola period. However, this article assumes, see above, that they are later additions from the Kandy period and that originally the statues ot the deities had no shrine rooms but were simple placed in niches of the original outer temple wall, which is now the inner wall of the corridor.

The western Devale, just behind the Digge hall, is dedicated to the warrior god Kataragama on his peacock. The northern shrine is for the mountain god Saman and that on the opposite southern side for the deified demon Vibhishana. There are two smaller Devales facing east. There are separate gates of these two shrines, one to the left and one to the right of the main entrance of the Buddhist shrine. In the southeastern corner, Vishnu is venerated, whereas the elephant-headed Ganesha has its shrine in the northeastern corner.

Those shrines of Hindu deities venerated also by Sinhalese Buddhists are called Devales, whereas Kovils are shrines of Tamil Hindus. Hidden behind curtains, the idols of the Devales are placed in niches of what was once the outer wall of the original Gampola-period temple building and is still the exterior wall of the central Buddhist shrine room. Each of the five Devales of the Lankatilaka has its own entrance, but four of the doors are almost always closed. The western door is sometimes opened or a key can be arranged by temple servants. As all five Devales are connected by a joint vestibule, all five statues of the Hindu gods can be visited from the western entrance. The corridors are quite narrow and have asymmetric barrel-vaulted roofs, leaning against the inner wall. This construction type quite typical for ambulatories of temples from earlier periods, too. Thus, it would come to no surprise, if this ring of aisles would be from the late medieval Gampola period. However, this article assumes, see above, that they are later additions from the Kandy period and that originally the statues ot the deities had no shrine rooms but were simple placed in niches of the original outer temple wall, which is now the inner wall of the corridor.

The western Devale, just behind the Digge hall, is dedicated to the warrior god Kataragama on his peacock. The northern shrine is for the mountain god Saman and that on the opposite southern side for the deified demon Vibhishana. There are two smaller Devales facing east. There are separate gates of these two shrines, one to the left and one to the right of the main entrance of the Buddhist shrine. In the southeastern corner, Vishnu is venerated, whereas the elephant-headed Ganesha has its shrine in the northeastern corner.

UpulvanUpulvan, set in a narrow shrine in the southeastern corner, was the most venerated god in the Gampola and Kotte periods. Since the Kandy period, Upulvan has been identified with Vishnu. This is why the statue, which is from a later period, depicts him with four hands. Upulvan means "colour of blue water lily". Confusingly, figures of blue-coloured mythology are very often depicted as dark grey or dark green in Indian art.

|

VibhishanaThe southern Devale is dedicated to Vibhishana, brother of Lanka's mighty demon king Ravana who abducted Rama's wife Sita. Vibhishana criticized that crime and helped Rama to free Sita. Rama rewarded Vibhishana by appointing him king of Lanka after Ravana's death. Sinhala Buddhists do not venerate Rama, but Vibhishana is guardian deity of the west of the island. As a demon, he has dark skin and tusks. His wife is known as Sarama.

|

KataragamaThe western shrine of Lankatilaka is that of Kataragama, known as warrior god Murugan in South India and Skanda in the Brahmanic Sanskrit tradition. Kataragama, whose skin colour is red, is the deity which has the most Devales. Although of foreign origin, he is held in high esteem by Sinhalese. Kataragama is depicted six-headed or in a very feminine way, the latter symbolizes his youth and beauty. His chariot is the peacock.

|

SamanThe northern shrine has Saman, a Yakkha demon, one of the aboriginal inhabitants of Sri Lanka according to Buddhist tradition. Saman was the first who converted to Buddhism when Lord Buddha visited the island. He therefore became the guadian of the religion. In particular, Saman is the protector of Adam's Peak, Ratnapura and the hillcountry. His colour is light. Usually, he is seen with a white elephant and not with a consort.

|

GanapathiPlaced in the northeastern corner, the occurence of Ganesha, also known as Ganapathi in Pali or Pulleyar in Sinhala, is somewhat strange among the group of supreme deities. He is usually not considered to be one of the highest gods of the Buddhist island. His shrine might be a concession to Tamils or to local traditions. In the late Middle Ages, Ganesha and Skanda were also identified with beings venerated by Mahayanist.

|

Satara Varam Deviyo - the "Four Paramount Deities" of Sinhalese Buddhism

In Buddhism, there is no believe in a creator deity or in a universal ruler of the world, because such a being could not be considered a superior or supreme being, as it would also be responsible for worldly suffering. The supreme beings according to Buddhist faith are those that have overcome the causes of suffering, Buddhas are such beings. Many Buddhist scholars don‘t hesitate to call their faith atheistic, atheistic in a sense of explicitely denying the existence of an ethically relevant being that is in charge of everything.

Nevertheless, the Buddhist tradition has never completely denied the existence of gods, only the existence of gods that are superior to a Buddha. The Buddha himself taught, that maintaining the traditional religious worship of gods and supporting priests - not only monks of his own Sangha - is helpful to safeguard order and stability. But faith in gods can only be helpful in worldly affairs, it is irrelevant or, as a bond, contraproductive on the path to salvation. However, even early Buddhism knew a religious exercise called "Devatanussati", which means nothing more than "god-viewing". It is not faith in their powers to help on the way to salvation, but a meditation practice gaining insight in the structure of this world. What is relevant on the way to salvation, is this mental activity, not the effects exercised by other beings, quite the contrary, salvation is liberation from those effects.

Apart from being objects of meditation practices, gods can be powerful beings according to Buddhist faith. Fertility and health, as intramundane goals, are believed to be dependent on supernatural beings. Believe in gods may not be required to be a Buddhist, but Buddhism does not explicitely deny their existence or their important role in worldly affairs. This is why Buddhism left local beliefs and worships of gods and ghosts untouched when it spread to other regions.

The result is that in the case of Sri Lanka the pre-Buddhist Sinhalese religion continued to play a role in the Buddhist era and that religious practices remained to be open for integrating new concepts of supranatural beings.

In Sri Lanka, there has been a hierarchy of superhuman beings up to the present time. Subordinate local deities could differ from region to region, even from village to village. Only in recent decades, the worship of local gods seems to have been decreasing, although it still occurs.Similar to beliefs in other Asian countries, many of these local deities are believed to have once been human heroes who were killed in a crue way and who, after their death, became ghosts who could bring harm or benefit. These ghosts are quite similar to the so-called Nats in Myanmar, which is a Theravada Buddhist country, too. But ghosts of Myanmar are not worshipped in Sri Lanka and the other way around.

Besides local ghosts, there are other gods that are venerated in larger regions. At the top of the hierarchy of the Sinhalese folk religion are gods that are in charge of the main regions of the island, namely the northern plains that were once the Anuradhapura kingdom, the southeastern plains that were once the Rohana principalities, the wetlands in the west and the mountains. Each of these principal parts of the island is protected by its own superior god, but – in contrast to typical local and regional deities on the lower levels of the hierarchy - all of these four principal gods of Sri Lanka are venerated in all parts of Sri Lanka. For example, the god of the south has temples in the highlands, too.

So who are these four highest gods of Sinhalese popular religion? The answer is: It depends. It depends on the historical era. There are no canonical scriptures giving the names of these highest gods once and for all. Even their number can sometimes be five insteead of four, as in the case of Lankatilaka.

Today, the highest Sinhalese gods are those venerated in the Four Devales at the Tooth Temple in Kandy, namely Vishnu, Kataragama, Natha and Pattini. Of these, Natha is the local god of Kandy. In other regions, Natha was considered to be a Bodhisattva, this means an even higher being than a god. But he was not known as one of the island‘s four highest gods before the Kandy period. Pattini, a goddess of South Indian origin, became popular only under the last Kandyan kings, who were of South Indian origin themselves.

Since the Kandyan era, Vishnu has been regarded as the highest of them all. At the begin of the Kandy period, this pan-Indien deity became to be identified with Upulvan (Upallavana in Pali language), a deity not known in India but mentioned in Sri Lanka‘s ancient Buddhist chronicles as protector of the Buddhist faith.

Kataragama is somewhat an exemption. Today, his temple is set apart from the other three in Kandy and is maintained by Tamil Hindu priests instead of Kapurala priests serving the other three gods. Kapuralas can be Sinhalese. Of the highest gods venerated in Kandy today, Kataragama is the only one who seems to have been part of the Satara Varam Deviyo, the "Four Paramount Deities" of Sinhalese Buddhism, right from the beginning. Until the Gampola period, Upulvan, Kataragama, Saman and Vibhishana were regarded as those principal gods protecting Sri Lanka and its Buddhist faith. Of these, only the name of Kataragama still remains as one of the divine „Big Four“ in Kandy. Kataragama is the god of the hills and the south, the ancient Rohana. Vibhishana is the God of the West, and Saman is Lord of the mountains, particularly Adams‘s Peak and of the Sabaragamuwa Province between central highlands and the range of the Sinharaja hills.

Concerning his regional origin or predominance, Upulvan is the most difficult case. He is considered the God of the northern plains, mainly today‘s Cultural Triangle, which corresponds to the ancient land called "Rajarata". This had been the most populated part of the island till the 13th century. But surprisingly, in the Cultural Triangle there is no accumulation of temples for Upulvan. And his most famous temple is at Dondra, at the southern tip of Sri Lanka. Upulvan seems to be a kind of primus inter pares, considered to be the highest god of the entire island.

Number two in significance is Kataragama. Kataragama is an immigrated God who had to fight for his rank in the southern region of the island, which finally became his home. This god has the largest number of temples in Sri Lanka, as he is venerated by Buddhists and Hindus and Weddahs and even by some Muslims (as a prophet).

Under his Tamil name, Murugan, this deity plays an even important role in southern India. He can therefore be called god of the Tamil people. Murugan cult is older than Brahmanism among Tamils in South India. The Brahmin priests from northern India who played increasingly important roles at the princely courts in southern India during the medieval period, interpreted the Tamil deity Murugan as the god Skanda known to them from their Sanskrit texts. The reason is, that both Murugan of the Tamil south and Skanda of the Sanskrit north are warrior gods. In the course of time the Tamils of South India and Sri Lankan became predominantly Shivaite (whereas Vishnu-worship is more widespread in northern India). But the pre-Brahmin origin of Murugan can still be seen from the fact that southindian priests of most Murugan temples are not members of Brahmin castes.

By and large, the original Tamil religion of South India was neither worship Vedic gods such as Indra or Mithra (an exception is Varuna) nor popular Puranic deities such as Vishnu, Krishna, Shiva or Durga. Rather, the pre-Brahmanic Tamil pantheon of South India consisted of four or five highest gods, which were associated with the different parts of the Tamil region. Murugan was the god of the hills, the regions where the herdsmen lived. Unlike peasants of the river valleys, the Tamil nomads form the hillcountry were belligerent - and so was their god Murugan. Animal sacrifices were practiced at some of his remote temples until recently.

The parallel to the Sinhalese pantheon of four or five gods for different landscapes is obvious, although in the Sinhalese traditon the criterion of the cardinal directions is more significant than that of landscape and culture forms as in the case of Tamila Nadu. However, there are more similarities between the highest gods of the pre-Brahmanic Tamils of South India and the Buddhist Sinhalese of Sri Lanka. Among the four Tamil principal deities, Mayon was considered to be the highest, with the color blue being assigned to him. The number two was Ceyon or Murugan, his color is red. This exactly corresponds to Upulvan and Kataragama in Sri Lanka. The two other gods of the Tamil pantheon, on the other hand, were less distinctive characters, their characters and names could change in the course of history.

The astonishing conclusion of this excursion is that the Pantheon of today's Sinhalese people is largely that of the early Tamil culture, two thousand years ago. In the course of the centuries, Tamils have become followers of Shiva, who is of almost no signifcance for Sinhalese Buddhists. In other words: The Buddhist Sinhalese people of Sri Lanka have better preserved what was once the original pre-Brahmanic pantheon of Tamils. This might come to a surprise who believe in an ethnic antagnonism rooted deep in history and resulting diverse cultural traditions: Sinhalese Buddhists worship the same principal gods as Tamils did, before they became Shivaites. In other words: Concerning the pantheon of four or five highest gods, Sinhalese and the Tamil roots are almost the same. Actually, it‘s no surprise considering the nature of the Buddhist faith mentioned above: It does not replace older traditions of worship of ghosts or gods. They can continue to be the same. This is not the case in a system of beliefs that is concerned with a ranking of the gods. Those who think, Shiva is the supreme being, as most Tamils do today, cannot confess a pantheon of four other highest gods. Instead of this, they have to subordinate them: Hence, Murugan alias Kataragama becomes the son of Shiva.

The close interconnection of Tamil and Sinhala culture and religion, which manifests itself not only in this pantheon of four principal gods, should not be downplayed in favour of common Western schemes of thought, which tend to believe in parallel developments of cultural plants from their diverse and specific and very own historical roots. According to Buddhist faith, this typical Western concept, although such identity-theories have become increasingly popular among Asian intellectuals after the colonial period and due to Western education, is misleading particularly when researching Asian cultural history, as interdependency, the key concept of Buddhist thought, is a more appropriate axiom for reasoning and explanations of cultural phenomenons.

Getting back to the five Hindu deities of Lankatilaka: The daily puja ceremonies at the the Buddha sculpture and at the five statues of the Hindu gods were similar to each other during the Gampola period. Furthermore, the annual processions at the Lankatilaka Vihara combined worship of the Buddha and of the five deities. Today, the procession of the Sacred Tooth in Kandy, the famous Esala Perahera, is also celebrated by the Buddhist Tooth temple and its four adjoining Hindu Devales together, in this respect quite similar to the medieval example of Lankatilaka, although there is now an obvious hierarchical gradient between the worship of the Buddha's tooth and the Hindu‘ deities. Nevertheless, the German scholar Hans-Dieter Evers assumed, that the medieval rites of the Lankatilaka temple were predecessors or inspirations of modern Kandy Peraheras.

Lankatilaka's temple concept as religious exaltation of a powerless king

The German sociologist Hans-Dieter Evers, now known as expert in the field of development policies, studied at the University of Ceylon in the early 1960s. Afterwards, he published several minor but authoritative studies on the social history of the island nation, standing out against common simplifying thought patterns that are dividing people into ethnic or religious groups by attributing specific identities.

Evers regards the Gampola period as the climax of a religious syncretism of Theravada, Mahayana, and Hindu elements in Sri Lanka's history of Buddhism, reflecting influences from Southeast Asia where similar syncretisms served to exalt the monarch by defining his power in a sacral manner. According to Evers, the idea of divine kingship, becoming increasingly important after the Polonnaruwa period, comes to a culmination point at the Lankatilaka temple. The king‘s dwindling secular power is thereby compensated by an even higher cosmic position of the monarchy.

Accommodation near Lankatilaka Viharaya

Most foreign visitors of the Lankatilaka temple arrive from Kandy, where a wide range of hotels and guesthouses is available, more than in any other town of Sri Lanka, except from the capital. The three Western Temples - Gadaladeniya, Lankatilaka and Embekke - can be reached on a half-day excursion from Kandy. They can also be part of sightseeing tours on a transfer day from Kandy to Nuwara Eliya.

For those arriving from Colombo who like to avoid the traffic jams of Kandy and Peradeniya or for travellers interested in visiting Lankatilaka in the early morning or late afternoon hours, accommodation is available in closer proximity, too. In Pilimathalawa, which is situated at the Colombo-Kandy mainroad (A1), just 6 km to the north of Lankatilaka and only 1 km north of Gadaladeniya, there are several cheap guesthouses and also a modern 2-star hotel called Urban Castle.

In Gampola, which is to the south of Lankatilaka Vihara, there is a Tourist Inn called Sama Uyana Bungalow, providing a small swimming pool. The rooms are simple, not too expensive. Like most hotels of Kandy, Gampola's Sama Uyana Bungalow is in 17 km distance from the Lankatilaka temple, but in a much quieter location, in a tea garden with panoramic views.

Regrettably, neither Urban Castle nor Sama Uyana pay commissions for being mentioned on our excellent Lankatilaka page. We forgot to ask them.

For those arriving from Colombo who like to avoid the traffic jams of Kandy and Peradeniya or for travellers interested in visiting Lankatilaka in the early morning or late afternoon hours, accommodation is available in closer proximity, too. In Pilimathalawa, which is situated at the Colombo-Kandy mainroad (A1), just 6 km to the north of Lankatilaka and only 1 km north of Gadaladeniya, there are several cheap guesthouses and also a modern 2-star hotel called Urban Castle.

In Gampola, which is to the south of Lankatilaka Vihara, there is a Tourist Inn called Sama Uyana Bungalow, providing a small swimming pool. The rooms are simple, not too expensive. Like most hotels of Kandy, Gampola's Sama Uyana Bungalow is in 17 km distance from the Lankatilaka temple, but in a much quieter location, in a tea garden with panoramic views.

Regrettably, neither Urban Castle nor Sama Uyana pay commissions for being mentioned on our excellent Lankatilaka page. We forgot to ask them.