|

Gal Vihara,

Polonnaruwa’s world-famous group of rock-cut statues - a sedentary, a standing and a wonderfully carved reclining Buddha - is a masterpiece of art of the ancient Sinhalese civilization. Let's quote Sir James Emerson Tennant: |

"This rock-hewn shrine

strictly Kalugal-vihare, the black rock (granite) Temple stands unrivalled due to its special features, the most impressive antiquity par excellence to be seen in the island, Ceylon and possibly not rivaled throughout the continent of India." |

Polonnaruwa's rock-hewn Buddha Statues - in brief

"Gal Vihara", also spelt "Gal Viharaya", means “Rock Monastery”. It's the name of Sri Lanka’s most celebrated rock-cut Buddha statues. They once belonged to the Uttara Rama, meaning “Northern temple”, founded by Polonnaruwa’s great King Parakramabahu I (1153-86). The Gal Vihara group consists of four fascinating statues, three colossal rock-cut images and a smaller one in a partly artificial cave. The Gal Vihara sculptures, each different in design, are undoubtedly the most perfect specimen of Buddha statues hewn out of solid granite in Sri Lanka. All four images are hallowed out of the abrupt eastern slope of a single massive boulder, which is about 27 meters in length and 10 meters in height. They are still in a good state of preservation. In order to protect them from acid rain, the resplendent images are sheltered under a new roof, the aesthetic perfection of which might be debatable.

History of the Gal Vihara rock temple - and its rediscovery

The Gal Vihara appears to mentioned in Sri Lanka’s ancient chronicle, the Mahavamsa, or more precisely, it’s second part which is sometimes referred to as the Chulavamsa. The Culavamsa part was writen during the Polonnaruwa and Dambadeniya periods, most probably under the Kings Parakramabahu I and Parakramabahu II respectively. The Gal Viahra’s name given in the chronicle is Uttara Rama, meaning “northern monastery”. The name refers to its location in the northern part of the capital Polonnaruwa and just north of the main monastic complex which is called Alahena Parivena today.

The Chronicle attributes a sedent and a reclining Buddha of the Uttara Rama to the great King Parakramabahu I. (1152-86). It does not not mention a standing Buddha statue, which contributes to some speculation concerning the time of origin and the identification of the standing rock statue of the Gal Vihara group.

Polonnaruwa’s Gal Vihara marks an important development in Buddhist history. The rock sculptures are remarkable in many respects. Though they still bear traces of Mayanist influences, the recling Buddha in particular is a new form of rock-cut Buddhas indicating a shift from worship of supernatural giant Buddhas to the more human form of the historical Buddha. Accordingly, the rock inscriptions of the Gal Vihara are significant sources of a principal development in the island’s Buddhist history: They record a monastic reform under the auspices of King Parakramabahu I, the result of which was the unification of the previous three monastic traditions (Nikayas), now in accordance with the Mahavihara tradition, which was purely Theravadic. From then on, Theravada has remained to be the predominant, or some say: sole form of Buddhism on the island. Parakramabahu’s Buddhist reform, documented at the Gal Vihara in Polonnaruwa, is of significance of Southeast Asian religious history, too. The pure form of Theravada Buddhism in Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia became predemoninant there, too, namely under the name “Sinhalese” or “Mahavihara” school.

After the fall of Polonnaruwa in the middle of the 13th century, caused by the maroding troops of the invader Kalinga Magha, Polonnaruwa fell into decay. Though the imposing rock statues have never been unknown to locals, who indeed created the modern name “Gal Vihara” or “Kalugala Viharaya” for them, the statues in the jungles were an exciting discovery for British explorers in the 19th century.

The first colonial officer who visited the Gal Vihara statues and reported about them, was Lieutenant Fagan in 1820.

Major Jonathan Forbes mentioned the rock-cut statues of Polonnaruwa in his famous travel log “Eleven Years in Ceylon”, first published in 1840 in London.

Samuel Baker, who later on became famous as explorer of the River Nile, saw the Gal Vihara rock statues and made a record of them in one of his first books, “Eight Years' Wanderings In Ceylon”, published in 1855.

Photos of the sculptures were taken for the first time in 1858. In the begin of the 1860s, Sir James Emerson Tennant, a noteworthy colonial secretary of Ceylon 1845-1850, described the Gal Vihara, too. But the first scientific account was written by James Ferguson in his “History of Indian and Eastern Architecture”, punlished 1910 in London). The report of British Ceylon’s most famous Archaelogical Commissioner, H.C.P. Bell mentioning his predecessors is cited below, given at the end of this webpage.

The Chronicle attributes a sedent and a reclining Buddha of the Uttara Rama to the great King Parakramabahu I. (1152-86). It does not not mention a standing Buddha statue, which contributes to some speculation concerning the time of origin and the identification of the standing rock statue of the Gal Vihara group.

Polonnaruwa’s Gal Vihara marks an important development in Buddhist history. The rock sculptures are remarkable in many respects. Though they still bear traces of Mayanist influences, the recling Buddha in particular is a new form of rock-cut Buddhas indicating a shift from worship of supernatural giant Buddhas to the more human form of the historical Buddha. Accordingly, the rock inscriptions of the Gal Vihara are significant sources of a principal development in the island’s Buddhist history: They record a monastic reform under the auspices of King Parakramabahu I, the result of which was the unification of the previous three monastic traditions (Nikayas), now in accordance with the Mahavihara tradition, which was purely Theravadic. From then on, Theravada has remained to be the predominant, or some say: sole form of Buddhism on the island. Parakramabahu’s Buddhist reform, documented at the Gal Vihara in Polonnaruwa, is of significance of Southeast Asian religious history, too. The pure form of Theravada Buddhism in Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia became predemoninant there, too, namely under the name “Sinhalese” or “Mahavihara” school.

After the fall of Polonnaruwa in the middle of the 13th century, caused by the maroding troops of the invader Kalinga Magha, Polonnaruwa fell into decay. Though the imposing rock statues have never been unknown to locals, who indeed created the modern name “Gal Vihara” or “Kalugala Viharaya” for them, the statues in the jungles were an exciting discovery for British explorers in the 19th century.

The first colonial officer who visited the Gal Vihara statues and reported about them, was Lieutenant Fagan in 1820.

Major Jonathan Forbes mentioned the rock-cut statues of Polonnaruwa in his famous travel log “Eleven Years in Ceylon”, first published in 1840 in London.

Samuel Baker, who later on became famous as explorer of the River Nile, saw the Gal Vihara rock statues and made a record of them in one of his first books, “Eight Years' Wanderings In Ceylon”, published in 1855.

Photos of the sculptures were taken for the first time in 1858. In the begin of the 1860s, Sir James Emerson Tennant, a noteworthy colonial secretary of Ceylon 1845-1850, described the Gal Vihara, too. But the first scientific account was written by James Ferguson in his “History of Indian and Eastern Architecture”, punlished 1910 in London). The report of British Ceylon’s most famous Archaelogical Commissioner, H.C.P. Bell mentioning his predecessors is cited below, given at the end of this webpage.

Sedentary Buddha - Vijjadhara Guha

The four sites of the Buddha statues of the Gal Vihara are called “caves”, though the three huge ones are not posted below rock sheltered but sculptured in partly artificial rock niches, except from the one small Buddha image seated in a cave indeed. The Gal Vihara rock measures 52 m (170 ft) in length, Along the 26 m long centrepiece, the rock is 10 m high, it then falls away gradually towards each end.

Sockets cut into the rock just behind the statues indicate that the walls had originally separated the statue from one another. Accordingly, remnants of brick foundations walls testify that each of the four figures was enshrined in a separate image house. The images were not intended to decorate a rock surface picturesquely but to be venerated inside shrine rooms, three of them with vaulted brick walls. Those “cave rooms” were only illuminated by small windows and candle light. This means, originally the immense statues were not exposed to sunshine as today. The figures were once plastered and painted in the same manner as other images in Sri Lanka’s cave temples.

The southernmost of the fours “caves” is Vijjadhara Guha, also transcribed Vijjadhdharaguha. The huge artificial alcove contains the island’s largest ancient image of a sedent Buddha, measuring 4.6 m (15 ft. 2.5 in) in height. The serene exquisitely carved Vijjadharaguha Buddha Image is regarded as one of Asia’s best specimen of seated rock statues at all. It’s cut back 5 m (17 ft.) for the shrine of the colossal sedentary Buddha statue.

The seated Vijjadharaguha sculpture is depicted in the common meditation gesture, which is called Samadhi Mudra or Dhyani Mudra, both hands are placed on the lap, right hand on left with fingers fully stretched. The-flame like symbol of enlightenment over the head of Buddha is called Siraspata.

The imposing rock-cut Vijjadharaguha figure sits on a throne, an Asana, the front of which is decorated with lions and thunderbolt symbols. The latter are noteworthy, because “Vajras”, as they are called, are indicating influence of the Tantic form of Mahayana Buddhism, which is otherwise even more alien to the Polonnaruwa art than to the previous Anuradhapura period.

Behind the head of the Vijjadharaguha Buddha is a bas-relief of a halo. The entire figure is framed by a relief in the shape of an arch, which is called Prabhamandala in Indian art. It resembles a Torana, a wooden gate, which is richly ornamented. Heads of the mythical crocodile-dragons called Makaras can be seen projecting on either side, holding small lions in their mouths. The upper part of the arch carries small celestial palaces or shrines with bas reliefs depicting Buddhas in their front niches or entrances.

Due to some Tantric symbolism of the Asana and the Prabhamandala, it has been speculated that the Vijjadharaguha Buddha does not represent the historical Buddha Shakyamuni but the cosmic Buddha Vairocana, one of the eternal Adibuddhas in Tantric Buddhism. The four small images of Buddhas or Bodhisattvas, all of them in Samadhi Mudra, too, could then represent the four directions of the universe, like in a Tantric Mandala.

Sockets cut into the rock just behind the statues indicate that the walls had originally separated the statue from one another. Accordingly, remnants of brick foundations walls testify that each of the four figures was enshrined in a separate image house. The images were not intended to decorate a rock surface picturesquely but to be venerated inside shrine rooms, three of them with vaulted brick walls. Those “cave rooms” were only illuminated by small windows and candle light. This means, originally the immense statues were not exposed to sunshine as today. The figures were once plastered and painted in the same manner as other images in Sri Lanka’s cave temples.

The southernmost of the fours “caves” is Vijjadhara Guha, also transcribed Vijjadhdharaguha. The huge artificial alcove contains the island’s largest ancient image of a sedent Buddha, measuring 4.6 m (15 ft. 2.5 in) in height. The serene exquisitely carved Vijjadharaguha Buddha Image is regarded as one of Asia’s best specimen of seated rock statues at all. It’s cut back 5 m (17 ft.) for the shrine of the colossal sedentary Buddha statue.

The seated Vijjadharaguha sculpture is depicted in the common meditation gesture, which is called Samadhi Mudra or Dhyani Mudra, both hands are placed on the lap, right hand on left with fingers fully stretched. The-flame like symbol of enlightenment over the head of Buddha is called Siraspata.

The imposing rock-cut Vijjadharaguha figure sits on a throne, an Asana, the front of which is decorated with lions and thunderbolt symbols. The latter are noteworthy, because “Vajras”, as they are called, are indicating influence of the Tantic form of Mahayana Buddhism, which is otherwise even more alien to the Polonnaruwa art than to the previous Anuradhapura period.

Behind the head of the Vijjadharaguha Buddha is a bas-relief of a halo. The entire figure is framed by a relief in the shape of an arch, which is called Prabhamandala in Indian art. It resembles a Torana, a wooden gate, which is richly ornamented. Heads of the mythical crocodile-dragons called Makaras can be seen projecting on either side, holding small lions in their mouths. The upper part of the arch carries small celestial palaces or shrines with bas reliefs depicting Buddhas in their front niches or entrances.

Due to some Tantric symbolism of the Asana and the Prabhamandala, it has been speculated that the Vijjadharaguha Buddha does not represent the historical Buddha Shakyamuni but the cosmic Buddha Vairocana, one of the eternal Adibuddhas in Tantric Buddhism. The four small images of Buddhas or Bodhisattvas, all of them in Samadhi Mudra, too, could then represent the four directions of the universe, like in a Tantric Mandala.

Cave Statue - Nisinnapatima Guha

There is only one cave room at the Gal Vihara which is hallowed out of the solid rock as a complete shrine room, using the rock as its ceiling. Presumably, this was a natural cave artificially enlarged to a rectangular cave room. The Pali name is Nisinnapatimaguha. This so-called “Excavated Cave” of Polonnaruwa’s Gal Vihara is the only example of an ancient cave in Sri Lanka, which is man-made and therefore resembling Buddhist cave temples of mainland India. Traces of wall-paintings can be seen on the walls of the Nisinnapatimaguha cave, too.

The Excavated Cave, too, houses a rock-carved sedent Buddha sculpture in Samadhi Mudra. Measuring 1.4 m (4 ft. 7 in.) in height, the image inside the cave is of course much smaller in size than the neighbouring Vijjadharaguha Buddha, but it’s excellently carved and charming indeed. This rock-cut image is seated on an almost 1 m high pedestal, a Padmasana, which means “Lotos Seat”. The Nisinnapatimaguha Buddha is depicted under a parasol. Only the body of this sedentary Buddha is framed by a Prabhamandala arch, which is of rectangular form. Makara-Dragons are displayed in anupright position. Besides the foot of the arch, there are two noteworthy figures depicting attendants with flywhisks. Flywhisks are called “chamara” or “prakirnaka” in Indian art. In Tantric Buddhism, they represent the sweeping away of obstacles to enlightenment. In Hindu art, flywhisks are emblems of royal dignity and souvereignty.

The halo surrounding the head is clearly marked. On either side of the head are minuscule images of Brahma to the right and Vishnu to the left of the of the Nisinnapatimaguha Buddha, both guardian deities are depicted four-armed.

The Excavated Cave, too, houses a rock-carved sedent Buddha sculpture in Samadhi Mudra. Measuring 1.4 m (4 ft. 7 in.) in height, the image inside the cave is of course much smaller in size than the neighbouring Vijjadharaguha Buddha, but it’s excellently carved and charming indeed. This rock-cut image is seated on an almost 1 m high pedestal, a Padmasana, which means “Lotos Seat”. The Nisinnapatimaguha Buddha is depicted under a parasol. Only the body of this sedentary Buddha is framed by a Prabhamandala arch, which is of rectangular form. Makara-Dragons are displayed in anupright position. Besides the foot of the arch, there are two noteworthy figures depicting attendants with flywhisks. Flywhisks are called “chamara” or “prakirnaka” in Indian art. In Tantric Buddhism, they represent the sweeping away of obstacles to enlightenment. In Hindu art, flywhisks are emblems of royal dignity and souvereignty.

The halo surrounding the head is clearly marked. On either side of the head are minuscule images of Brahma to the right and Vishnu to the left of the of the Nisinnapatimaguha Buddha, both guardian deities are depicted four-armed.

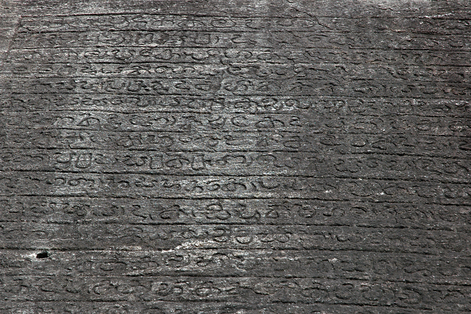

Gal Vihara rock inscription - Parakramabahu's monastic reform

Next to the entrance of Excavated Cave (Nisinnapatima Guha) is the famous Gal Vihara inscription on the sloping rock between the cave and the standing image. It’s one of Sri Lanka’s longest ancient inscriptions at all. It contains the records of King Parakramabahu I. about his convening of a Buddhist council in 1165 in order to restore the order by establishment of rules for good conduct and monastic discipline. Many monks, who had children or were engaged in magical rituals, which is not in accordance with the Vinaya rules of the Sangha, were expelled from the Buddhist order.

In particular, this Gal Vihara rock insciption mentions the king's efforts to unite the Buddhist order under a single Nikaya tradition, that of the ancient Mahavihara.

Convening a council, purifying the order from monks’ bad conduct, unifying the Sangha as well as well as recording this in inscription, all of this belongs to a tradition of significant Buddhist kings established by none other than the famous Indian Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century B.C.E. After periods of corruption of monastic discipline, important Sri Lankan Kings were engaged in restructuring the Sangha. Parakramabahu the Great is the best example. Such edicts are called Katikavata in Sri Lankan history.

Accordingly, the text quotes the king: “Seeing again and again a blot on the immaculate Buddhist religion if a mighty monarch like myself were to remain indifferent the religion might perish and many living beings would be destined for hell. Let me serve the religion that it might last a thousand years”.

The new code of conduct for monks was drawn up with the help of the most renowned monk of the Polonnaruwa period, Mahakassapa from Dimbulagala, who followed the Theravadic traditions of the Sri Lanka’s most ancient monastery, the Mahavihara in Anuradhapura. Mahakassapa became the “Sangharaja”, the “King of the Buddhist Order”. Though the period of a unified Sangha under a hierarchical leadership disappeared again with the fall of Polonnaruwa, there is one legacy of Parakramabahu’s Sangha reform lasting in Sri Lanka till the present day. It was from Parakramabahu’s Buddhist Council onwards, that the Theravada school of Buddhism, the “Elders’ Teaching”, has been the sole accepted form of Buddhism on the island. In this respect, the significance of the events recorded in the Gal Vihara inscription cannot be underestimated for the culture of Sri Lanka and beyond.

That the Sri Lankan Buddhist tradition was held in high esteem during that period, can be learned from the account of a Tibetan envoy who visited Bodhgaya, the holiest place of worship in India for all Buddhists. His report from 1235 states, he counted 300 Sinhales monks at the Buddhist main shrine, who were in charge of keeping the sacred place intact.

In particular, this Gal Vihara rock insciption mentions the king's efforts to unite the Buddhist order under a single Nikaya tradition, that of the ancient Mahavihara.

Convening a council, purifying the order from monks’ bad conduct, unifying the Sangha as well as well as recording this in inscription, all of this belongs to a tradition of significant Buddhist kings established by none other than the famous Indian Emperor Ashoka in the 3rd century B.C.E. After periods of corruption of monastic discipline, important Sri Lankan Kings were engaged in restructuring the Sangha. Parakramabahu the Great is the best example. Such edicts are called Katikavata in Sri Lankan history.

Accordingly, the text quotes the king: “Seeing again and again a blot on the immaculate Buddhist religion if a mighty monarch like myself were to remain indifferent the religion might perish and many living beings would be destined for hell. Let me serve the religion that it might last a thousand years”.

The new code of conduct for monks was drawn up with the help of the most renowned monk of the Polonnaruwa period, Mahakassapa from Dimbulagala, who followed the Theravadic traditions of the Sri Lanka’s most ancient monastery, the Mahavihara in Anuradhapura. Mahakassapa became the “Sangharaja”, the “King of the Buddhist Order”. Though the period of a unified Sangha under a hierarchical leadership disappeared again with the fall of Polonnaruwa, there is one legacy of Parakramabahu’s Sangha reform lasting in Sri Lanka till the present day. It was from Parakramabahu’s Buddhist Council onwards, that the Theravada school of Buddhism, the “Elders’ Teaching”, has been the sole accepted form of Buddhism on the island. In this respect, the significance of the events recorded in the Gal Vihara inscription cannot be underestimated for the culture of Sri Lanka and beyond.

That the Sri Lankan Buddhist tradition was held in high esteem during that period, can be learned from the account of a Tibetan envoy who visited Bodhgaya, the holiest place of worship in India for all Buddhists. His report from 1235 states, he counted 300 Sinhales monks at the Buddhist main shrine, who were in charge of keeping the sacred place intact.

Actually, the Vinaya rules layed down by the Buddha himself do not allow the intervention of laymen such as kings into affairs of the Sangha. Of course, a king has no authority to change or proclaim monastic rules. The Katikavatas did not alter the canonical Vinaya but introduced additional rules for securing the observance of the original Vinaya rules. For example, King Parakramabahu decreed that new ordination ceremonies had to be held only in the capital, Polonnaruwa, on a specific festival day and in the presence of the king. The most important administrational means for securing monastic discipline was that monks had to acquire a certificate of the king. This meant, noone could falsely claim to be a monk any more, as it had happended previously. This practice of royal or governmental certififications for monks is a practice which was borrowed from the Sri Lankan Katikavata tradition in other Theravada Buddhist countries, too, in mainland Southeast Asia, particularly in Thailand.

Nevertheless, in practice this meant that a layman, the king, was able to decide who could become a monk. And actually this is not in accordance with the original Vinaya rule of the Buddha, that emphasized the strict autonomy of the order, especially concerning the admission of new members of the Sangha. Furthermore, Parakramabahu’s rule that the leadership of the capital’s monastery was in charge of regional and local communities of monks, is against wording and spirit of the original Vinaya rule of the Buddha who decreed, that all competences are attributed to the local congregations. Indeed, the Buddha seems to have intended to avoid a hierarchical structure in favour of democratic autonomy of each monastic community.

Standing Gal Vihara Statue - Utthitapatima Guha

The rock-cut statue is 7 m (23 ft) tall statue. It’s a masterpiece of art and stonemasonry. The identity of the standing figure of Polonnaruwa’s Gal Vihara group is one of the most controversial issues in Buddhist art history. Popular belief as well as many educated tour guides consider it to be a depiction of Ananda, the Buddha’s favourite disciple, mourning besides the reclining Buddha statue, which definitely represents the passing away of the Master. Nevertheless, it is much more likely, that this mystic standing rock statue of Gal Vihara is a Buddha image.

The 78th chapter of the Mahawansa (belonging to the part called Chulavansa) states that Parakrama caused cunning workmen to make three caves in the rock, the cave of the spirits of knowledge, the cave of the sitting image, and the cave of the sleeping image. No mention is made of the standing image. But the brick foundation could provide evidence this separate cave with the standing image was a later addition, just to add a "standing posture" to the already existing sedent and recumbent ones in order to assemble all three common postures of Buddha stues in Sri Lanka. Others expain the missing reference in the chronicles in just the opposite way: The standing image is earlier, maybe from the same period as Sri Lanka’s other rock-hewn status such as Aukana Buddha. Both the latter explanation is not entirely convincing. The styles of the upright ant the nearby lying statue in Polonnaruwa are quite similar, particular the round face and the elaborate but very thin garment of the standing statue resemble those of the other Gal Vihara statues much more than those of rock-cut statues from the previous Anuradhapura period.

The main reason for the controversy and for identifying this marvellous statue as Ananda is the gesture of crossing the hands on the chest. Sri Lanka’s most renowned archaeologist, Senarat Paranavitana, was of the opinion that it represents the Buddha himself in grief, namely as Paradukkha-dukkhita, this is sorrowing for the sorrows of others. Similarly, other authors believe that this Buddha statue depicts the Buddha’s great compassiontowards all sentinent beings, which is called “Maha Karuna”.

Today’s most widely accepted theory was put forward by Prof. Leelananda Prematilleke, former Head of the renowned Department of Archaeology of the University of Peradeniya and Coordinating Director of the UNESCO - Sri Lanka Project of the Cultural Triangle. He assumed that the upright statue of Gal Vihara represents the Buddha in the second week after attaining enlightenment. He spent this week paying respect to the Bodhi tree and the lotus seat below the tree. Therefore a Bodhi tree was planted recently there by the custodians of the Cultural Triangle Project.

The 78th chapter of the Mahawansa (belonging to the part called Chulavansa) states that Parakrama caused cunning workmen to make three caves in the rock, the cave of the spirits of knowledge, the cave of the sitting image, and the cave of the sleeping image. No mention is made of the standing image. But the brick foundation could provide evidence this separate cave with the standing image was a later addition, just to add a "standing posture" to the already existing sedent and recumbent ones in order to assemble all three common postures of Buddha stues in Sri Lanka. Others expain the missing reference in the chronicles in just the opposite way: The standing image is earlier, maybe from the same period as Sri Lanka’s other rock-hewn status such as Aukana Buddha. Both the latter explanation is not entirely convincing. The styles of the upright ant the nearby lying statue in Polonnaruwa are quite similar, particular the round face and the elaborate but very thin garment of the standing statue resemble those of the other Gal Vihara statues much more than those of rock-cut statues from the previous Anuradhapura period.

The main reason for the controversy and for identifying this marvellous statue as Ananda is the gesture of crossing the hands on the chest. Sri Lanka’s most renowned archaeologist, Senarat Paranavitana, was of the opinion that it represents the Buddha himself in grief, namely as Paradukkha-dukkhita, this is sorrowing for the sorrows of others. Similarly, other authors believe that this Buddha statue depicts the Buddha’s great compassiontowards all sentinent beings, which is called “Maha Karuna”.

Today’s most widely accepted theory was put forward by Prof. Leelananda Prematilleke, former Head of the renowned Department of Archaeology of the University of Peradeniya and Coordinating Director of the UNESCO - Sri Lanka Project of the Cultural Triangle. He assumed that the upright statue of Gal Vihara represents the Buddha in the second week after attaining enlightenment. He spent this week paying respect to the Bodhi tree and the lotus seat below the tree. Therefore a Bodhi tree was planted recently there by the custodians of the Cultural Triangle Project.

AnimisachetiyaThe most celebrated standing Buddha image at Gal Vihara, dated to the Polonnaruva period,

bears the most controversial gesture in Buddhist iconography, the gesture of crossing the hands on the chest. As this gesture is not known in Indian Buddha images, the exact iconographical meaning of the gesture has engendered controvery among scholars. S.M. Burrows and S. Paranavitana opine that this peculiar mudra is a gesture of sorrow. Gunapala Senadeera identifies it as gesture of meditation. However, this gesture, though not shown by Indian Buddha images, is known as the Svatika Mudra in Hindu art. In Hindu art, to pay homage to a supreme god, several statues of attendants perform the cross-handed gesture. It neither means sadness nor meditation, but devotion. The cross-handed gesture is found mostly in South Indian art, examples of sculptures in Svastika Mudra were created during several periods of the first millennium, such as Amaravati, Pallava, Western Chalukya and Chola. One example of Svastika Mudra in India is Buddhist, but neither depicting a Buddha nor one of his diciples. It is a Bodhisattva statue in cave 12 in Ellora. It is posted in front of the Garbhagriha containing the Budda image, paying hommage to the Buddha. However, outside India there are examples of depictions of the Buddha showing him paying hommage with the Svatika Mudra, not to other beings but to places and symbols of Enlightenment or Nirvana. This is why Prof. Leelananda Prematilleke identified the upright image of the Gal Vihara as a representation of Animisachetiya (also transcribed “Animisacetiya”), or Anamisasatthana (also transcribed “Animisa Satthana”). The latter term refers an event in the second week after the Buddha’s enlightenment, whereas “Animasachetiya” is the name of the place of this event. In the second week after attaining Buddhahood the Buddha meditating in standing posture, gazing without blinking to the place of his enlightenment, which is marked by his seat and the Bodhi tree. “Animisa” means “unblinking”. This miracle story of the Buddha’s one week long unblinking gaze is told in some Pali scriptures of Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia. One such biography of the Buddha, composed in Sri Lanka, is the Jinacharita. The scene of the Animisachetiya, showing the Buddha gazing towards the Bo-Tree, is depicted in the Kandyan murals of the Dambulla cave temple. In this painting, the Buddha in front of the Bodhi Tree shows the same gesture of devotion as at the Gal Vihara in Polonnaruwa, the hands crossed in front of the chest. The Buddha is paying hommage to the Bo-Tree. The Jinacharita reads: “For one week, [the Buddha] stood paying homage to the Bodhi tree and to the throne of victory by his unblinking lotus-like eyes.” The legend of Aminisacetiya is also depicted in Kandy-period murals in the cave temple of Hindagala. There is more supporting evidence for this interpretation from Southeast Asia. In medieval Myanmar (Burma), the cross-handed Svastika Mudra was used for illustrations of the Animisachetiya legend in the Powintaung cave from the Ava period (14th to 16th century). The cross-handed gesture for the Animisachetiya is also found in the art of Laos ad Lan-Na (today’s northern Thailand). Animisachetiya illustrations of the Buddha are also known from classical Thai art, an example can be found in Wat Koh Kaew Suddharam in the Siamese capital Ayyuthiya. Eventually, this gesture became quite popular in Thailand’s Ratanakosin style of art in the 19th centuries. There are sveral examples of Animisachetiya illustrations with cross-handed gesture in Bangkok, for example at Wat Suthat, known to tourists as the “Temple of the giant Swing”. Most notably, a relief of a Buddha displaying the Svatika Mudra in front of a Bo Tree was found at a slab of a Bai Sema (monastic boundary) in Wat Bueng Khum Ngoen. This Buddhist monastery is located in the Yasothon Province in the northeastern region of Thauland which is known as Isan. This part of Thailand was not under control of the Dvaravati Kingdom during the first millennium C.E. Surprisingly, the Bai Sema slab is nonetheless an example of Dvaravati art. And this is definitely earlier than the Polonnaruwa period. Hence, there is an example of a depiction of a Buddha in the Svastika gesture of devotion illustrating the Animisachetiya some centuries prior to the creation of the Standing Buddha of Polonnaruwa’s Gal Vihara. During the Polonaruwa period, starting already in the 11th century, monastic and cultural contacts between Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia had been intensified. There are many examples of influences of Southeast Asian architecture in Pollonnaruwa. So it would come as no surprise, if too the Gal Vihara group is influenced by both Indian Hindu and Southeast Asian Buddhist art. This is why the interpretation of Prof. Prematilleke is very conclusive. If he is correct, the statue is the Buddha and not Ananda.

|

Pro interpreting of the upright figure as Ananda+ The chronicle states that King Parakramabahu donated a sedentary and a recumbent Buddha, but a standing Buddha statue is not mentioned.

+ Crossing the arms in front of the breast is a gesture of devotion, expressing veneration for a higher being, but there is no higher being than a Buddha he could venerate. Contra identification as Ananda statue* Buddha images with crossed arms are uncommon but not completely unknown. There are many examples in Southeast Asia, and at least one of them is earlier than the Gal Vihara standing statue. Standing Buddha statues with crossed armes are also known from the later Kandyan art in Sri Lanka.

* Disciples like Ananda are usually depicted baldheaded. Curles indicate a depiction of a Buddha. * The elongated ears of the statue are typical for Buddha images, not a feature of diciples. * In Buddhist iconography, the Padmasana, a pedestal in the form of a lotus throne, is usually reserved for Buddha statues. * The grieving Ananda is usually depicted at the feet of a dying Buddha, not at his head. * It is clear, from the marks in the rock and the brick foundation walls in front of it, that the standing statue of Gal Vihara had a separate shrine, where it was the principal idol of veneration, which would be unthinkable for a statue of Ananda. The term "Svastika Mudra" (Swastika Mudra) is not unambiguous. It does not only designate the posture of crossed arms, but also other gestures, for example a hand gesture only splaying and interlocking the fingers, or an arm posture with hands stretched forward horizontally, similar to Pataka Mudra, but with hands crossed at the wrist.

|

Reclining Buddha of Polonnaruwa - Nipannapatima Guha

Sri Lanka’s iconic Gal Vihara Reclining Buddha is 14 m (46 ft) long. In spite of the colossal dimensions, the statue is graceful and resonating with peace. The liquid flow of the robes over the body has been much admired.

The soles of the Buddha's feet are decorated with a lotus blossom and other auspicious marks of royalty or Buddhahood.

Typically for the Polonnaruwa period, the Gal Vihara Reclining Buddha has a round face with a high forehead. The feet are not entirely parallel as it would be for sleeping Buddhas. The The left foot of the Buddha resting on the right is slightly drawn back. In Buddhist iconography, this is a feature marking the moment of the passing-away and attaining the final Nirvana. which is called Mahaparinirvana in Sanskrit and Mahaparinibbana in Pali.

There is a debate, if this is nevertheless a depiction of a sleeping Buddha instead of an expiring Buddha. The reason is: If the upright standing statue nearby is not Ananda, then there are no attendents. Earlier Indian representations of the Mahapariniravana usually show Ananda and some more disciples standing at the feet of the Buddha.

The sleeping Buddha is a much more common motive in Sri Lankan art than the expiring Buddha. This is why some interpret this image as a depiction of a sleeping Buddha in the so-called “Lion Posture” (Sihasana or Sinhasana). It’s also called the “pose of the sleeping lion”, as the lion sleeps resting its head on its paw.

The Buddha rests his head on an elaborately decorated cylindrical pillow, the carving of which is carefully executed. It has a slight depression under the weight of the head. The pillow is decorated with the Chakra, the eternal wheel. The very centre of the pillow shows a so-called “Lion-Face” (Kirthimukha).

The so called “Cave of Reclining Image” (“Nipannapatima Guha”) was indeed an image house with brick walls on three sides. The image house once sheltering this impressive recumbent sculpture had its own separate entrance and two windows additionally.

The soles of the Buddha's feet are decorated with a lotus blossom and other auspicious marks of royalty or Buddhahood.

Typically for the Polonnaruwa period, the Gal Vihara Reclining Buddha has a round face with a high forehead. The feet are not entirely parallel as it would be for sleeping Buddhas. The The left foot of the Buddha resting on the right is slightly drawn back. In Buddhist iconography, this is a feature marking the moment of the passing-away and attaining the final Nirvana. which is called Mahaparinirvana in Sanskrit and Mahaparinibbana in Pali.

There is a debate, if this is nevertheless a depiction of a sleeping Buddha instead of an expiring Buddha. The reason is: If the upright standing statue nearby is not Ananda, then there are no attendents. Earlier Indian representations of the Mahapariniravana usually show Ananda and some more disciples standing at the feet of the Buddha.

The sleeping Buddha is a much more common motive in Sri Lankan art than the expiring Buddha. This is why some interpret this image as a depiction of a sleeping Buddha in the so-called “Lion Posture” (Sihasana or Sinhasana). It’s also called the “pose of the sleeping lion”, as the lion sleeps resting its head on its paw.

The Buddha rests his head on an elaborately decorated cylindrical pillow, the carving of which is carefully executed. It has a slight depression under the weight of the head. The pillow is decorated with the Chakra, the eternal wheel. The very centre of the pillow shows a so-called “Lion-Face” (Kirthimukha).

The so called “Cave of Reclining Image” (“Nipannapatima Guha”) was indeed an image house with brick walls on three sides. The image house once sheltering this impressive recumbent sculpture had its own separate entrance and two windows additionally.

Location of Gal Vihara in Polonnaruwa

Quotation of Archaeological Commissioner's

H.C.P. Bell's 1907 report on the Gal Vihara in Polonnaruwa

|

"Excavations were limited in 1907 to two important temples, the Buddhist " Gal Vihare" and

Siva Devale No. 1—that chief of the Hindu shrines of Polonnaruwa—for the past seventy years at least strangely mistermed "Dalada Maligawa." Both these sites are characteristic of the semiantagonistic faiths which ruled at Polonnaruwa, at times with that tacit rivalry and mutual toleration of broad-minded religionists, anon, when the tide of fanaticism rose beyond control, ousting each other's fanes and wrecking the images. "Gal Vihare." The first site attacked was the " Gal Vihare." This rock-hewn shrine—strictly " Kalugal Vihare," or "the Black rock (granite) Temple "—stands unrivalled as, in its special features, the most impressive antiquity par excellence to be seen in the Island of Ceylon, and possibly not rivalled throughout the Continent of India. The fine of gigantic figures carved from the gray rock which forms their background, calm, immovable, majestic, amid the hush of the surrounding forest, gazing ever fixedly into space with the pensiveness of profound meditation, or wrapped in eternal slumber, must inspire in the thoughtful beholder wonder and admiration, mingled with an instinctive sense of silent awe. The irresistible charm and sublimity of the " Gal Vihare " could not but appeal forcibly to the few observant visitors who, for the last century, have chanced to view it in its peaceful wooded seclusion untouched by axe and spade. Their impressions (recorded below) leave little need for further " general description." It remains but to marshal in order those necessary, if dry-as-dust, details and measurements which an Archaeological Report is bound to furnish forth for scientists and others interested in such minutiae. Lieut. Fagan, who found his way to Polonnaruwa nearly a hundred years ago (1820), pushed energetic exploration of the jungle-buried ruins as far north as the " Gal Vihare " : On advancing about half a mile further in the jungle I came upon what at first view appeared a large black rock, about 80 ft. long and 30 high in the centre, and sloping towards the ends, and on advancing a few steps further found myself under a black and gigantic human figure at least 25 ft. high. I cannot describe what I felt at the moment. On examination I found this to bo a figure of Budhoo in an upright posture, of excellent proportions and in an attitude, I think, uncommon, his hands laid gracefully across his breast and his robe falling from his left arm. Close on his left lies another gigantic figure of the same sacred personage, in the usual recumbent posture. I climbed up to examine it more minutely and found that the space between the eyes measured one foot, the length of the nose 2 ft. 4 in., and the little finger of the hand under his head 2 feet. The size of the figure may be guessed from these proportions. On the left of the standing figure is a small door of the Vihari, and on the right of the door another figure of the god of the same proportions as the former two and in the common sitting attitude. These figures are cut out clear from the rocks, and finely executed ; but whether each is formed of one or more pieces I forgot to examine. The entrance to the Vihari is arched with a pilaster on each side cut out of the rock, the old wooden door in good preservation. Within sits Budhoo on a throne, a little above the human size with his usual many headed and many-handed attendants. The apartment is narrow and the ceiling low and painted in red ornament, the whole resembling others that I have seen in the Seven Corles, Matale, &c. Between the door and the standing figure the rock is made smooth for about 6 ft. square, and this space is covered with a close written Kandian [sic] inscription perfectly legible. I may have overlooked many interesting points in this great monument of superstition, but it was nearly dark and I was obliged to return to Topary. Various names are assigned by the people to the other buildings, but they all agree in calling this Galle Vihari. (1) Twenty years afterwards (1841) Major Forbes included a description of the " Gal Vihare " in his notice of the ancient structures of Poloimaruwa : Projecting from the perpendicular face of a large rock, in the strongest relief, are three colossal figures of Buddha : they are in the usual positions, sitting, standing, and reclining ; the last-mentioned being upwards of forty feet in length. According to minute directions which the Cingalese possess, these positions of Gautama are, and his features ought to be, retained without variation. Between the sitting and standing figures, the Isuramuni [sic], or Kalugalla wihare, has been cut in the hard rock. In this cavern-temple part of the stone has been left, and afterwards shaped into the figure of Buddha seated on a throne : the two pillars in front of this wihare are also part of the solid rock. These works were completed in the twelfth century, and in the reign of Prakrama Bahoo ; yet are not only undecayed, but the most minute ornaments are sharp and undiminished by time or weather. (2) Some fourteen years later (1855) Sir Samuel Baker, whose sporting propensities took him far afield, thus describes " the rock temple" as he saw it in 1855 : At the further extremity of the main street, close to the opposite entrance gate, is the rock temple with the massive idols of Buddha flanking the entrance . . . . . . . . . . The most interesting, as being the most perfect, specimen is the small rock temple, which, being hewn out of the solid stone, is still in complete preservation. This is a small chamber in the face of an abrupt rock, which doubtless, being partly a natural cavern, has been enlarged to the present size by the chisel ; and the entrance, which may have been originally a small hole, has been shaped into an arched doorway. The interior is not more than perhaps twenty-five feet by eighteen, and is simply fitted up with an altar and the three figures [sic] of Buddha, in the positions in which he is usually represented, the sitting, the reclining, and the standing postures. The exterior of the temple is far more interesting. The narrow archway is flanked on either side by two inclined planes, hewn from the face of the rock, about eighteen feet high by twelve in width. These are completely covered with an inscription in the old Pali [sic] language, which has never been translated. Upon the left of one plane is a kind of sunken area hewn out of the rock, in which sits a colossal figure of Buddha, about twenty feet in height. On the right of the other plane is a figure of standing posture about the same height. Still further to the right, likewise hewn from the solid rock, is an immense figure in the recumbent posture, which is about fifty-six feet [sic] in length, or, as I measured it, not quite nineteen paces. These figures are of a far superior class of sculpture to the idols usually seen in Ceylon, especially that in the reclining posture, in which the impression of the head upon the pillow is so well executed that the massive pillow of gneiss rock actually appears yielding to the weight of the head. This temple is supposed to be coeval with the city, which was founded about 300 years before Christ [sic] and is supposed to have been in ruins for upwards of 600 years. (3) Sir Emerson Tennent's too brief notice (1860) of the " Gal Vihare" is best known. It is illustrated by a reliable woodcut : The most remarkable of all the antiquities at Topare, is the Gal-wihara, a rock temple hollowed in the face of a cliff of granitic stone which overhangs the level plain at the north of the city. So far as I am aware it is the only example in Ceylon of an attempt to fashion an architectural design out of the rock after the manner of tho cave temples of Ajunta and Ellora. The temple itself is a little cell, with entrances between columns ; and an altar at the rear on which is a sedent statue of Buddha, admirably carved, all forming undetached parts of the living rock. Outside, to the left, is a second sedent figure, of more colossal dimensions, and still more richly decorated. To the right are two statues likewise of Buddha, in the usual attitudes of exhortation and repose. The length of the reclining figure to the right is forty-five feet, the upright one is twenty-three, and the sitting statue to the left sixteen feet from the pedestal to the crown of the head. Between the little temple and the upright statue the face of the rock has been sloped and levelled to receive a verbose inscription, no doubt commemorative of the virtues and munificence of the founder. The Mahawanso records the formation of this rock temple by Prakrama Bahu, at the close of the twelfth century, and describes the attitude of the statues "in a sitting and a lying posture, which he caused to be hewn in the same stone." With the date thus authenticated, one cannot avoid being struck by the fact that the art exhibited in the execution of these singular monuments of Ceylon was far in advance of that which was provalent in Europe at tho period when they were erected. (4) In 1858 Mr. J. W. Birch of the Civil Service and Lieut. R. W. Stewart, R. E., visited Polonnaruwa, and were probably the first to photograph its ruins. This is all they have to say of the " Gal Vihare": From the face of a long rock near are carved stone figures of Buddha, in the sitting, standing, and recumbent postures. Between the sitting and standing figures is a small temple hollowed out of the solid rock, with an altar piece and figure of Buddha inside. On a part of the rock, which is flattened like a plane, are cut several lines of an inscription, apparently in the Nagari [sic] character. It is a very beautiful work, and is generally called the Kalugala Vihare , though it is referred to occasionally in the books as Isura Muni Vihara. It is said to have been executed by the orders of Prakrama Bahu. (5) Within a few years (1876) Fergusson's " History of Architecture " provided archaeologists with the first account by an expert : If not the oldest, certainly the most interesting group at Pollonarua is that of the rock-cut sculptures known as the Gal Vihara. They are not rock-cut temples in the sense in which the term is understood in India, being neither residences nor chaitya halls. On the left, on the face of the rock, is a figure of Buddha, seated in the usual cross-legged conventional attitude, 16 ft. in height, and backed by a throne of exceeding richness : perhaps the most elaborate specimen of its class known to exist anywhere. Next to this is a cell, with two pillars in front, on the back wall of which is another seated figure of Buddha, but certainly of a more modern aspect than that last described ; that appearance may, however, be owing to whitewash and paint which have been most liberally applied to it. Beyond this is a figure of Buddha, standing in the open air; and still further to the right another of him, lying down in the conventional attitude of his attaining Nirvana. This figure is 45 ft. long, while the standing one is only 25 ft. high. These Nirvana figures are rare in India, but there is one in the most modern cave at Ajunta, No. 26, and others in the latest caves at Nassick and Salsette. None of these, however, so far as I know, ever attained in India such dimensions as these. In another century or two they might have done so, but the attainment of such colossal proportions is a sure sign of their being very modern. (6) Finally, Mr. Burrows in his "Guide to the Buried Cities" has furnished almost the latest description of Ceylon's archaeological chef d'oeuvre in rock : The " Gal Vihara " (rock temple) consists of three figures of heroic size, and a shrine containing a smaller figure ; they are all carved out of the same abrupt boulder of dark granite. The southernmost figure represents the sedent Buddha in the conventional attitude, and is 15 ft. high above the pedestal. The back ground of the figure is elaborately carved : from the squares of the pilasters dragons' heads project ; and from the mouth of each issues a small lion. Higher up are representations of Hindu pagodas. The pedestal on which the figure sits has a bold frieze of lions alternating with a curious emblem which may be a pair of dragons' heads [sic] reversed. Next to this figures comes the shrine, which is cut out of the solid rock, and contains a rock-cut sedent figure of Buddha, 4 ft. 7 in. high, seated on a pedestal 3 ft. high. The background of the figure is profusely decorated with " deviyos " (minor divinities) bearing torches, grotesque lions, lotuses, &c. ; and the pedestal of the statue has a frieze of alternate lions and the dragons' heads. The whole has unfortunately been much disfigured by modern attempts to paint it on the part of a priest whose enterprise was in advance of his taste. Between the shrine and upright figure , the face of the rock has been smoothed to receive a long inscription of no particular interest. It consists of 51 lines of writing, and measures 13 ft. 9 in. The erect figure, which is 23 ft. high, and stands on a circular pedestal ornamented with lotus leaves, represents " Ananda," the favourite disciple of Buddha, grieving for the loss, or rather the translation, of his master. The figure has generally been taken for a Buddha, but erroneously, as it is obviously not in the conventional attitude of the standing Buddha ; and further the Mahawanso distinctly states that King Parakkrama Bahu " caused statues of Buddha in a sitting and a lying posture to be carved out of the same rock," making no mention of an upright statue of Buddha. The reclining figure of Buddha is by far the finest of the three. It measures 46 ft. in length, and has suffered little from the ravages of time. The expression of complete repose upon the face, the listless attitude of the arm and hand, the carefully arranged folds of the robe, together with the extreme stillness of the surrounding jungle, combine to form a wonderful realisation of the ideal Nirvana." (7) cited from: H. C. P. BELL, C.C.S., Archaeological Commissioner [1911]. NORTH-CENTRAL, NORTHERN, AND CENTRAL PROVINCES. ANNUAL REPORT, 1907. Colombo: PRINTED BY H. C. COTTLE, GOVERNMENT PRINTER, CEYLON. pp. 7-9 ------- Bell quoted from: (1) Fagan, " Accounts of the Ruins of Tobari," 1820. (2) Forbes, " Eleven Years in Ceylon, " 1841, Vol. I., p. 416. (3) Baker, " Eight Years' Wandering in Ceylon," 1855 (4) Tennent, "Ceylon," Vol. II., pp. 593-6, 1860. The engravings of ruins are from sketches by Mr. A. Nicholl, R.H.A. (5) Ferguson, " Souvenirs of Ceylon," 1868, p. 113. Lieut. Stewart's photograph of the " Gal Vihara " has been amusingly "faked" for the more convenient re-arrangement of the figures. "Ananda" and the sedent Buddha occupy the left and right sides of the engraving, with the recumbent Buddha between, and the cave shrine behind, walled. Tennent's woodcut (1860) shows (perhaps purposely) no wall hiding the cave. (6) Fergusson, " History of Indian and Eastern Architecture," 1876, p. 200. (7) Burrows, " The Buried Cities of Ceylon," 1905, p. 109. |