Mulkirigala, also spelt Mulgirigala, is the most important heritage site in the Southern Province. In the hinterland of the coast, it’s the best example of a Sinhalese cave temple. There are plenty of caves used as image houses on different levels of the rock and the paintings in most of them are of excellent quality, though of a distinct style characteristic for the deep south of Sri Lanka. In a way, Mulkikirigala can be called the Dambulla of the south and the monadnock with its vertical cliffs resembles Sigiriya. Like Dambulla, Mulkirigala looks back to a long history. Monks lived in the rock shelters already in pre-Christian centuries.

Content of our Mulkirigala page:

Among tourists, the beautiful cave temple is not an unknown site, since it is mentioned in many pocket guides. On the other hand, Mulkirigala is not yet overcrowded. The rock temple in the hinterland of Tangalle is both an attractive place for heritage travellers and a rewarding destination for beach holiday makers who stay in one of Sri Lanka's south coast resorts.

There are two slightly different latinized forms of the name of this monastery both of which are used quite frequently: „Mulkirigala Rajamaha Vihara“ or „Mulgirigala Raja Maha Viharaya“.

Location of Mulkirigala

Mulkirigala, belonging to a region known as Giruva Pattuva in the western part of Hambantota District, situated 17 km north of the port town of Tangalle and 70 km east of Galle, the capital of the Southern Province. It can be reached within half an hour from the beaches of the southern coastal belt around Dickwella. Embilipitiya, the gateway to Udawalawe National Park, is 30 km to the northeast of Mulkirigala. When traveling from Tangalle or Dickwella or Matara to Udawalawe for an afternoon safari, it's worth considering a detour to Mulkirigala on the way. The Sinharaja Range, within sight of the peak of Mulkirigala Rock, is in 40 km distance to the north-northwest, as the crow flies.

History of Mulkirigala

According to a local legend, it was King Saddhatissa, the brother of the even more famous Dutthagamani, who founded this monastery in the second century BC. He had been hunting in this area when a local Vedda showed him a rock he proposed for a temple. The king found the rock to be perfectly suitable and named is Mu Kivu Gala, as this can translate to "the rock mentioned by him".

Two inscriptions in very ancient Brahmi letters, which mention donations to the order, prove that the caves of this over 100m high granite rock housed Buddhist reclusives already in the 2nd century BC. The rock monastery of Mulkirigala can therefore claim to be almost of the same age as Dambulla or Ridivihara and one of the oldest monasteries in the world that is inhabited by monks today.

Despite some claims it might have been mentioned in the Mahavamsa chronicle under a different name, it's not certain that the monastery of Mulkirigala is recorded in one of the ancient chronicles of the island, Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa, or in the medieval Chulavamsa, which became the second part of the Mahavamsa sequel. The chronicle Pujavaliya of the 13th century is the first one to report that Mulkirigala was founded by the early Anuradhapura kings in the first centuries of the Buddhist period.

Despite some claims it might have been mentioned in the Mahavamsa chronicle under a different name, it's not certain that the monastery of Mulkirigala is recorded in one of the ancient chronicles of the island, Dipavamsa and Mahavamsa, or in the medieval Chulavamsa, which became the second part of the Mahavamsa sequel. The chronicle Pujavaliya of the 13th century is the first one to report that Mulkirigala was founded by the early Anuradhapura kings in the first centuries of the Buddhist period.

However, Mulkirigala is believed to be the Giriba Vihara mentioned in the Bodhivamsa, a chronicle of the Bo-tree composed around the 10th century, as one of the first 32 temples that received a sapling of the Anuradhapura Bo-tree. Or it is identified as the Samuddagiri temple, which is said to be one of 64 temples founded by King Saddhatissa's father Kavantissa, then the regent of the south.

The Dutch, who ruled the coastal provinces in from in the second half of the 17th century and in the 18th century, called this rock as "Adam’s Berg", which translates to "Adam's Peak". It's a common hypothesis that they confused it with Sripada, the mountain known as Adam's Peak till the present day. However, it's more likely that they used the same name of two completely different places knowingly, one for the place where Adam left his first footprint after leaving paradise and one for the place of his tomb, the former being today's Adam's Peak and the latter referring to Mulkirigala Rock.

In the 18th century, it was a disciple of the founder of the Syam Nikaya in Kandy, Saranankara Thero, who became the first chief monk of the reestablished Mulkirigala monastery in the 18th century. Saranankara Thero had traveled to Siam, modern-day Thailand, for the purpose of reintroducing a line of ordination to restore the Buddhist monastic life in Sri Lanka. There is a commemoration stupa on the first terrace of the rock, placed just in front of the first painted cave next to the ticket booth,. The small stupa is dedicated to Vatarakgoda Dhammapala, who was Saranankara‘s disciple and refounder of the Mulkirigala temple.

The Dutch, who ruled the coastal provinces in from in the second half of the 17th century and in the 18th century, called this rock as "Adam’s Berg", which translates to "Adam's Peak". It's a common hypothesis that they confused it with Sripada, the mountain known as Adam's Peak till the present day. However, it's more likely that they used the same name of two completely different places knowingly, one for the place where Adam left his first footprint after leaving paradise and one for the place of his tomb, the former being today's Adam's Peak and the latter referring to Mulkirigala Rock.

In the 18th century, it was a disciple of the founder of the Syam Nikaya in Kandy, Saranankara Thero, who became the first chief monk of the reestablished Mulkirigala monastery in the 18th century. Saranankara Thero had traveled to Siam, modern-day Thailand, for the purpose of reintroducing a line of ordination to restore the Buddhist monastic life in Sri Lanka. There is a commemoration stupa on the first terrace of the rock, placed just in front of the first painted cave next to the ticket booth,. The small stupa is dedicated to Vatarakgoda Dhammapala, who was Saranankara‘s disciple and refounder of the Mulkirigala temple.

It was in the library of the Mulkirigala monastery that the British colonial officer and scholar George Turnour, who besides James Prinsep contributed much to decipher the inscriptions on the first discovered Pillar of Ashoka, discovered parts of the Mahavansa Chronicle and, even more significantly, he received transcriptions of exhaustive commentaries on this chronicle from the chief monk in 1826. The commentaries known as Mahavamsa-Tika were composed in the late Anuradhapura or early Polonnaruwa period. This commentary provides not only additional historical material from otherwise lost ancient sources. It also turned out to be extremely helpful to understand the text of the Mahavamsa written in Pali, as the commentary explains ambiguous Pali terms used in the chronicle. This discovery in Mulkirigala turned out to be a key for Turnour to prepare the first translation of the Mahavamsa into English, published in 1837. Only afterwards, the national chronicle was also translated into Sinhalese.

In a sense, Turnour‘s translation marks the starting point for researching further Pali texts, in particular the Buddhist Tipitaka canon. This project was was carried out by the Pali Text Society in London, which was founded for this purpose. The Pali Text Society played a decisive role in drawing interest in western nations to the religion of Buddhism and in its oldest documents, also for their scientific evaluation. This western science also had repercussions on Buddhism in Ceylon itself, as it partly opened up a new understanding of the original evidence of Buddhism. The new knowledge of the Mahavansa was also of inestimable value for the identification of the antiquities of Sri Lanka.

Mulkirigala Monastery

Today's monastery is small group of buildings at the foot of the rock, partly leaning against rocks and making use of natural shelters, but it‘s modern stone masonry for the most part. The assembly rooms and residential quarters are grouped around an inner courtyard. This patio-style ensemble, also known from temples in Kandy such as Malwatta, is modeled after the residences of the Kandyan highland nobility. This kind of monastic architecture is from a more recent period, as in the Kandy period buildings made of stone or brick were originally reserved either for royal residence or for shrine and ceremonial rooms only. In contrast, the monks' quarters, consisting of huts known as Kutis, were built from perishable material, just like secular peasant huts. In the Anuradhapura period, only supporting pillars had been made of stone in significant monasteries.

Mulkirigala Monastery has close ties to the Kandyan tradition of the highlands. Unlike most of the monasteries in the western and southern lowlands, it belongs to the Syam Nikaya, more precisely to the Malwatta branch of this "Siamese order", which has its headquarters in the monastery of the same name Kandy. After Malwatta and next to Ridivihara, Mulkirigala is one of the most respected monasteries of this branch. It was the Siam Nikaya that reestablished a monasery at this two millennia old temple mountain in the 18th century. Compared to most other monasteries of the Syam Nikaya, which are inhabited by only one or very few fully ordained monks, Mulkirigala is the residence of a comparatively large number of monks. About 10 fully ordained monks lived here in the early 21st century. Mulkirigala is also a respected training center for young novices, formong a so-called Pirivena (or Parivena in Pali). About two dozen novices are housed in Mulkirigala.

Sightseeing at Mulkirigala Rock

As with so many old hermit settlements and monasteries in Sri Lanka, Mulkirigala is a rock in the first place. The rock rises up to more than 200 m above sea level, the slopes are almost vertical at all sides, but it's easy to climb the rock via a flight of stairs at a less steep flank and in a natural chasm. Altogether, there are 533 steps leading to the summit.

Natural rock shelters were prepared by laymen to provide suitable accommodation for pious monks. It was important to make them more weatherproof in the first place. Mulkirigala Rock is one of those granite monadnock that are so typical of the plains of Sri Lanka.

Natural rock shelters were prepared by laymen to provide suitable accommodation for pious monks. It was important to make them more weatherproof in the first place. Mulkirigala Rock is one of those granite monadnock that are so typical of the plains of Sri Lanka.

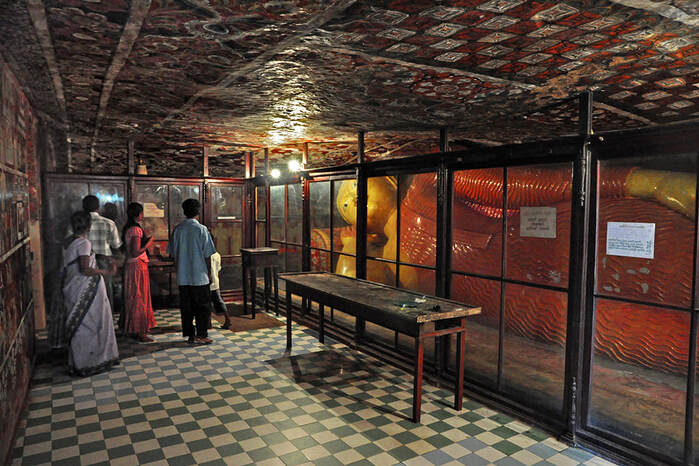

Paduma Rahat Vihara

The lower platform of the rock furthermore carries the temple‘s Bo-tree. This platform close to ground level gives access to the two most beautifully painted caves of Mulkirigala. This entire lower complex including the two painted caves is called Paduma Rahat Vihara. Each shelters a 14 m long recling Buddha, depicted in the state of Parinirvana, his final extinction, whereas most other reclining Buddhas in Sri Lanka - except from the ver large ones carved out of rocks - are not actually representations of his passing-away but showing him in sleeping position. The iconographic difference is only subtle. For example, the feet of a sleeping Buddha are exactly in parallel, wheres one foot has a very short inclination in the case of a dying Buddha.

In the first cave, a row of seated Buddhas is depicted under the ceiling. They represent the 28 Buddhas in Tushita heaven. This is the heaven where Bodhisattva Maitreya resides, who has accumulated such an amount of positice Karma in his previous lives that he can dwell in this pleasant heaven in his present life and will be reborn on earth and attain even greater perfection in his next life, namely Buddhahood. Maitreya is the future Buddha, awaited by Mahayana and Theravada Buddhists alike. A common belief is he will come to earth 5000 years after the previous Buddha Shakyamuni.

In the first cave, a row of seated Buddhas is depicted under the ceiling. They represent the 28 Buddhas in Tushita heaven. This is the heaven where Bodhisattva Maitreya resides, who has accumulated such an amount of positice Karma in his previous lives that he can dwell in this pleasant heaven in his present life and will be reborn on earth and attain even greater perfection in his next life, namely Buddhahood. Maitreya is the future Buddha, awaited by Mahayana and Theravada Buddhists alike. A common belief is he will come to earth 5000 years after the previous Buddha Shakyamuni.

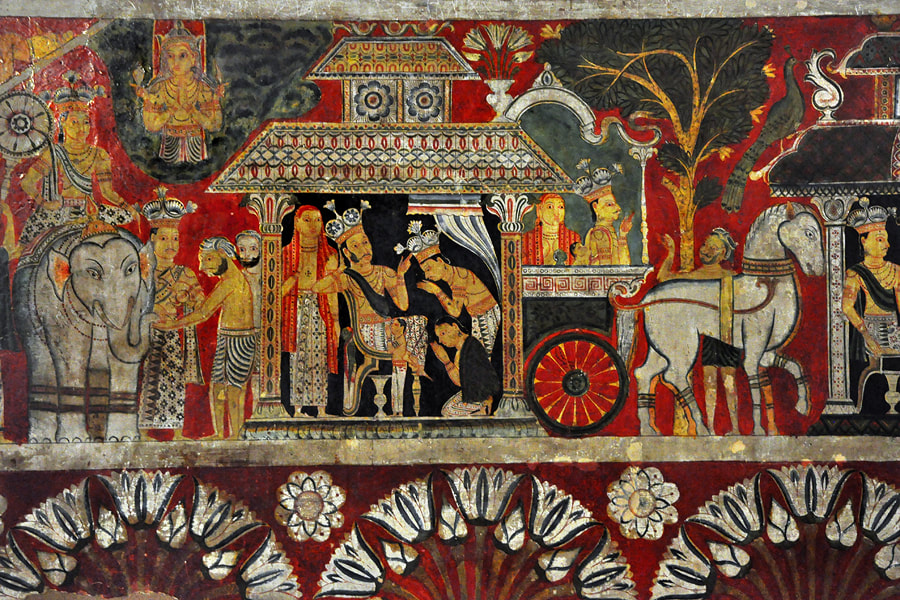

Traces of different layers of paintings can still be seen at the head end of the 14m long reclining Buddha. Overall, the paintings in this cave are from three different periods. The different layers are around 300, 200 and 100 years old respectively. Only the faded, pale ocher-coloured paintings date back to thej 18th century. This is the say they are originals from the Kandy period, when the monastery was reestablished by the monks of Syam-Nikaya. The later layers of murals that are dominating today are from the of the colonial era, albeit still in traditional Kandy style. Actually, most of the so-called Kandyan paintings in Sri Lanka are from the colonial period but perpetuate the Kandyan art.

However, the later paintings also show significant differences when compared to the classialc Kandyan paintings known from Dambulla or Degaldoruwa. A sppecific of the Mulkirigala paintings is use of shades of blue. In the late Kandy period, blue mineral colours could only obtained by importing lapis lazuli from Afghanistan. But this was expensive and was therefore the bluw colour is rarely used in original Kandy paintings. Lapis lazuli is also absent from the oldest frescoes in Mulkirigala, which by the way are the first Kandy paintings in the tropical lowlands of Sri Lanka. However, in the colonial era Europeans in coastal cities could purchase indigo, which was much cheaper than lapis lazuli and was used as a blue dye. Making use of indigo acquired from the coastal merchants, the 19th century paintings of Mulkirigalas are strikingly more colorful than those from the Kandy period. In general, the mural in Sri Lanka temples are not frescoes in a strict sense. Rather, tempera paints and binders made from oils were brushed on the plaster only after it had been dehumidified and completely dry.

However, the later paintings also show significant differences when compared to the classialc Kandyan paintings known from Dambulla or Degaldoruwa. A sppecific of the Mulkirigala paintings is use of shades of blue. In the late Kandy period, blue mineral colours could only obtained by importing lapis lazuli from Afghanistan. But this was expensive and was therefore the bluw colour is rarely used in original Kandy paintings. Lapis lazuli is also absent from the oldest frescoes in Mulkirigala, which by the way are the first Kandy paintings in the tropical lowlands of Sri Lanka. However, in the colonial era Europeans in coastal cities could purchase indigo, which was much cheaper than lapis lazuli and was used as a blue dye. Making use of indigo acquired from the coastal merchants, the 19th century paintings of Mulkirigalas are strikingly more colorful than those from the Kandy period. In general, the mural in Sri Lanka temples are not frescoes in a strict sense. Rather, tempera paints and binders made from oils were brushed on the plaster only after it had been dehumidified and completely dry.

Four Hindu gods are depicted on the narrow right side of the cave, which is the wall just behind the door. From left to right the deities are Vishnu, Skanda, Kataragama and, just behind the door, Saman. The latter is easily identifiable by the mountain in the background, which represents Siri Pada, the sacred mountain of the Buddha's footprint, which is known as Adam's Peak to Westerners. Saman is considered the patron god of this holy mountain and one of the major guardian deities of the Buddhist religion in Sri Lanka. He is therefore one of the highest gods of the Buddhist Sinhalese. But the deity known as Upulvan in Sri Lanka is held in even higher esteem, as a protector of the entire island. Due to the blue colour of his skin, Upulvan has been identified with the Hindu god Vishnu sind the late Middle Ages. As said, Vishnu can be seen to the left. The grim figure next to him is said to be the Indian god of war, Skanda. But with his fangs he looks more like a demon. It‘s more probable that this is a representation of the regional god Vibishana, the brother of demon king Ravana. Vibhishana is the guardian deity of the western lowlands of Sri Lanka. The main reason for not identifying the demonlike god with Skanda is that the res-coloured Kataragama Kataragama stands right next to him and Lord Kataragama is actually the regional manifestation of Skanda in southern Sri Lanka. It‘s highly unlikely that the same god is depicted twice in this group of four. Moreover, the said Kataragama portrait also has iconographic features tha are actually charactistics of Skanda, viz. twelve arms and the peacock as his mount.

Click for Background Information: 4 Highest Sinhalese Deities

Upulvan-Vishnu, Vibishana, Kataragama and Saman form a typical pantheon of four highest gods of the island, they symbolize the parts of Sri Lanka corresponding to the four cardinal directions. The south is Kataragama's country. Though local deities played an even more important role in every day religious life, a group of four was venerated on the entire island. This foursome has been at the top of the hierarchy of deities of the Buddhist Sinhalese since antiquity, though not always consisting of the very same gods. In the Kandyan period Natha, the guardian of the Kandy Valley, and Pattini, a female goddess of Southindian origin, finally replaced Vibhishana and Saman. It‘s all the more remarkable that Vibhishana and Saman reappear in a painting of the colonial period. This might be due to the fact that the centre of Sinhalese culture shifted slightly from the Kandyan hillcountry to the wetzone lowlands. Vibhishana, the god of the western plains, and Saman, the regional deity of the Ratnapura Valley at the foot of Adam‘s Peak, are the guardians of the population centres in the lowlands.

The four supraregional high gods can be interpreted in Sri Lanka as guardian deities of various parts of the country. But the concept of a foursome is not of Sinhalese origin. Rather, the pre-Brahmanic Tamil culture of southern India worshiped four gods as the highest ones, each of the four was related to a certain type of landscape more than to a specific region. The types of land in Tamil Nadu, namely mountainous areas, bushland, urban river plains or coastal areas also differed in culture. Later on, those old Tamil gods were interpreted by Brahmins as regional variants of the younger Hindu gods Shiva and Vishnu. Most present-day Tamils consider Shiva to be the supreme god. But the said ancient Tamil gods have not lost their dominance among the Sinhalese. It may come to a surprise that Sinhala Buddhists have preserved the old Tamil beliefs better than the Hindu Tamils themselves. But there is nothing unusual about such a shift of earlier traditions on the subcontinet. In a similar way, the ancient highestd gods of the Vedas, those of the Holy scriptures of Hinduism, such as Indra, hardly play a role in the religiosity of today's Hindus. The theology and also the iconography of today's Hinduism is actually much younger than Buddhism. The ancient pantheon of Vedic gods has not been preserved painstakingly, rather it has undergone a development in Hinduism. But unlike Brahmin priests, Buddhist monks were not interested in devoloping further stories about the realm of the gods and hardly took any notice of the beliefs of the lay people. As traditions of Brahmin priests played a much less significant role in Buddhist regions, the latter are more dominated by folk traditions and ofte have preserved pre-Brahmanic elements.

|

Just above the said paintings depicting the major gods and also on the wall in between the two doors of the cave, there is a sequence of figural paintings, depicting each person in a very uniform way. Each of them wears a robe and has a halo around the shirt-haired heads and a lotus flower in the right hand. These are the iconograhic charectiristics of Buddhist saints, the so called Arhats or Arahants, those human beings who through the guidance of the Buddha have achieved Nirvana.

|

Click For Explanation: What is an Arahant?

The Nirvana of Arahants is just the same state of mind as that of a Buddha. There are no differences in rank within the Nirvana. The distinction between Buddhas and Arahants is a worldly one. Arahants did not find awakening on their own but through the help of a Buddha, be it through study of his discourses of observance of his monastic rules. So every Buddhist who attains Nirvana is at least an "Arahant", a "saint". In contrast, those beings who find awakening through their own reflection on the Dharma of the worl, without any guidance ot assistance, are called Pacceka Buddhas in the Pali language or Pratyeka Buddhas in Sanskrit. However, most of these enlightened beings are fully satisfied with the achievement of the goal of enlightenment. Only very few of them also reach out to others and make the effort of helping them on their path to awakening. Only those who are engaged in this activity of helping others to become Arahants are called Buddhas. Strictly speaking, when Siddharta Gautama found enlightement und the Bodhi Tree, he only became Pratyeka Buddha. It was not prior to his first teaching sermon, known as "setting the wheel of teaching in motion", that he became a Buddha truly and fully.

According to the beliefs of Theravada Buddhists, in the course of history only a few hundred people have achieved Arahantship, i.e. found salvation. Those of the enlightene beings or saints that lived on the island are mentioned by names in Sri Lanka's oldest commentary on the canon. It is also believed that attaining Nirvana becomes increasingly difficult in the course of the centuries, as the temporal distance from the Buddha is an obstacle on this path. Orthodox Theravada Buddhists consider attaining Nirvana to be impossible in our present circumstances. Only in folk religion particularly respected living monks are sometimes venerated as Arahants. For example in Myanmar such Arahants are known. They usually do not hold a high office and underwent no specific right nor does their exist any process of canonization. They are simply venerated as saints by many lay people. Orthodox monks nowadays actually don‘t expect to attain Nirvana. Rather, the goal of the normal Theravada monk is basically the same as that of a layman, namely gaining good Karma for a more favorable rebirth. For this purpose, monastic life offers by far the best preconditions. However, the ultimate goal, Nirvana, isnot given up at all, but it‘s expected to be attained only in a later life. It‘s postponed, so to speak. In particular, monks hope to be able to accumulate such favourable Karma that they will one day be reborn as a disciple of the next Buddha Maitreya, in whose presence it will be easiest to achieve Arahantship, i.e. Nirvana.

The second cave, just next door, also houses a reclining Buddha of about the same size. The ceiling of this cave is conventionally decorated with murals depicting flowers of a simple and almost geometrical design. Most noteworthy is the the wall between the doors. The colourful and vivid mural illustrate scenes from the canonical Jataka stories, a very common theme of Kandy painting. The scenes are lined up in horizontal lines like in a picture book. By European standards, the pictures may not have much depth of perspective. But in comparison with the classic Kandy painting such as those in Degaldoruwa they show a more pronounced spatiality. For example, the figures overlap more often. And shades are also used.

|

The left side of the wall painting illustrates the Telapatta-Jataka the story of the oil bowl. The right side has the most popular story from one of the previous lives of the Buddha, namely the Vessantara Jataka. It is about the future Buddha ceding all his belongings, all prestige, even his children and ultimately his beloved wife for the benefit of others, when the gods tested his generosity.

|

Click for Explanation: What are Jatakas?

"Jata" means "birth". Jatakas are stories about the a being that is reborn in several forms, human and animal, in each life obtaining such good Karma that it finally was reborn as Shkayamunu, the Buddha. So Jatakas are about the previous lives of the Buddha. 550 such tales are preserved in the Tipitaka canon, as part of the Sutra collection. They are stories of edification and instruction. As the later Buddha Shakyamuni had been often reborn as an animal, many Jatakas are fables. They are probably of pre-Buddhist origin and were integrated into the Buddhist canon as illustrations of teachings about morals and Karma. Most of the „(re)birth tales“ are about generosity and sacrifice. The stories were particularly popular with the lay people, because they offered them what the monastic rules or the discourses could not provide: figurative moral instruction. Many of the oldest known fables of India are thus integrated into the text corpus of the Buddhist holy scriptures and have only been passed on in the Buddhist tradition.

Rock Inscription

Climbing the staircase to the upper terraces of the Mulkirigala rock, one can see an ancient rock inscription to the right, it‘s just at the beginning of the steep section behind a turn of the pathway to the left. Visitors can hardly miss it, as a board draws attention to it. The inscription, which is from around the 6th centur, mentions tha two lay people were released from their obligation to work for the monastery. This indirectly indicates that at that point time the monasteries were already powerful landlords of a status comparable to that of the royal court. A king could not only collect taxes, but the peasants also contributed corvee and worked the land of the king.

Meda Maluva Vihara

|

Further uphill, a path branching off to the left leads to a small pearly-white dagoba. It belongs to the second temple complex named Meda Maluva Vihara, which translates to "Middle Terrace Temple". In particular, the middle terrace has a so-called Devale, a shrine dedicated to a Hindu deity. This means it‘s a place of worship for Buddhist laypeople, because monks usually do not participate in the cult for gods, because the gods are part of the world of suffering that has to be overcome and they can help only in this world‘s affairs but not on the way to salvation. Representations of Vishnu and Kataragama can be seen at the Meda Maluva.

|

Raja Maha Vihara

Halfway up the rock, only a few meters above the tier of the Meda Maluva, the visitor enters the wide platform of the so-called Raja Maha Vihara through a small gate. There are even more painted caves at this terrace than at the Paduma Rahat Vihara at the foot of the rock. In front of the cave shrines is a small pond with another rock inscription at its edge. The text is from the 12th century, corresponding the Polonnaruwa period. It mentions the name of this place as Muhundgiri. The present name "Mulgiri-gala" might be derived from that historical term. The water of the pond is considered to be of healing power and curing female infertility.

The series of rock shelters of the Raja Maha Vihara terrace is now has four distinct painted caves. The one on the outer right side was decorated much later than the others and is somewhat gaudy.

The other three caves are more interesting, though their murals are not originals from the 18th century Kandy period. However, they are old, some definitely date back to the 19th century, and they represent the original style convincingly, as they are clearly based on the models from the Kandyan period. The largest cave contains another sleeping Buddha, which measures about 14 m in length.

The other three caves are more interesting, though their murals are not originals from the 18th century Kandy period. However, they are old, some definitely date back to the 19th century, and they represent the original style convincingly, as they are clearly based on the models from the Kandyan period. The largest cave contains another sleeping Buddha, which measures about 14 m in length.

The smalles cave, located at the end of the series of rock shelters, is called serpent cave or Naga Lena. A demon in the shape of a snake is said to live in the small room behind the door that is decorated with a cobra painting.

Even more interesting than the painted rock shelters shrines of this tier called Raja Maha Vihara tier might be the corridor in front of them. The doors from the corridors to the caves are framed by large Makara Toranas. They seem to be from the 20th century but are pretty perfect examples of this kind of carved arches.

Even more interesting than the painted rock shelters shrines of this tier called Raja Maha Vihara tier might be the corridor in front of them. The doors from the corridors to the caves are framed by large Makara Toranas. They seem to be from the 20th century but are pretty perfect examples of this kind of carved arches.

Click for explanation: What is a Makara?

The Makara is also often seen in Hindu art in India and has become popular at arches of Buddhist temples in Sri Lanka only after the Polonnaruwa period. The different animals that were combined to form this mythical creature can be clearly identified: In general Makaras are mythical sea monsters, usually resembling a crocodile or a dragon. They are also sometimes called sea elephants because they can have the head of an elephant and the body of a fish. A makara is a symbol of the forces of water, both life-giving and devastating. The colourful Makaras of Mulkirigala have the mouth of a crocodile, ends up in an elephant's trunk. The body is that of a scaly fish, the ears are of a pig, the teeth are of a monkey, the paws of a lion and the tail of a bird.

The original Kandy paintings next to the entrance to the largest cave, that with the reclining Buddha, are the most noteworthy ones. At the outside there are illustrations of scenes of the Jivi-Jataka. They are among the most famous paintings of southern of Sri Lanka, particularly the group of musicians in which a woman is depicted as a drummer for the first time in Sri Lankan art.

These less colourful paintings are originals from the Kandy period. They haven't even been restored since. Nevertheless they appear to be fresh and modern. Though illustrations of texts from the Buddhist canon, the clothing and customs give an impression of courtly style of Sri Lanka in the 18th century.

Abandoned Rock Shelters

On the tier of the four caves of the Raja Maha Vihara there is a short jungle path to the opposite side of the rock. Here are the earliest examples of monastic caves of Mulkirigala, rock shelters serving as humble accommodations of monks. They were not resdesigned as Kandyan style image houses later on but fell into decay. In contrast to the Indian rock monasteries, the natural caves have not been expanded but have remained largely natural in Sri Lanka. On the outside they were protected by a wall. In one of the caves is an old Makara Torana relief that will once have adorned a doorway. In the very last rock shelters is one of the oldest inscriptions of Mulkirigala.

Summit of the Mulkirigala Rock

The steepest section of the stairs then leads to the top of the rock. The total number of stairs from the foot of the rock to the summit is 533.

The summit is crowned by a new Bo-tree sanctuary and a pearly-white stupa. The major attraction, however, is the 360-degreee panorama, though now lett photogentic due the construction of a radia mast on the neighbouring rock at the beginniong of our century.

The summit is crowned by a new Bo-tree sanctuary and a pearly-white stupa. The major attraction, however, is the 360-degreee panorama, though now lett photogentic due the construction of a radia mast on the neighbouring rock at the beginniong of our century.

Favourable weather conditions provided, the ocean can be seen in the south and the mountains of the Singharaja rainforest in the north. Seen from above, the Deep South of Sri Lanka looks like a deserted forest, though it is a cultivation are. A hole in the rock forms a direct connection to the slope, it is said to have been gouged by a mythical snake.