Embekke Devale, also spelt Ambekka Devalaya, is one of the three so-called “Western Temples” which are situated to the west of Kandy and to the north of Gampola, the other two being Lankatilaka and Gadaladeniya. The Embekke Devale is often attributed to the Gampola period of the Late Middle Ages (14th century). The surviving structures of the Embekke Devale, however, are mainly from the Kandyan period. In contrast to the other two Western Temples, Embekke’s main shrine is Hindu, dedicated to Kataragama, but an attached shrine is Buddhist. In Lankatilaka and Gadaladeniya, it’s the other way around. The Hindu deity Kataragama, the Sri Lankan version of Skanda aka Murugan, is venerated by Buddhist Sinhalese, too.

|

Content of our Embekke page Location Names Legends History Structures Digge - drummers hall highlight: woodcarvings |

The main feature of the Embekke temple is a timber structure, whereas the main buildings of Gadaladeniya and Lankatilaka are made of dressed stone and brick respectively. More precisely, the feature Embekke is most famous for is the wooden Digge, the “Drummers’ Hall” in front of the main shrine. The pillars of this Digge carry the most excellent woodcarvings from the Kandyan period, altogether there are more than 100 specimen, many of which are masterpieces. Besides ornaments, they show human beings and mythical animals including fabulous creatures, secular and religious scenes alike. Almost every motif is represented by more than one carving, but the design of each is unique, for example the ways of depicting the clothing differ. Embekke has earned a reputation of being the village of woodcarvers till the present day. Several workshops are in the immediate neighbourhood of the temple.

|

Location of the Embekke temple

|

Embekke, a village situated in the historical Medapalata Korale or today's Udunuwara Divisional Secretariat in Kandy District, is situated 10 km north of Gampola and 16 km southwest of Kandy by road. The temple, named Embekke Devale or Ambekka Devalaya, is located 1 km to the west of the village of the same name, the temple's separate ribbon-built hamlet is at the road to Lankatilala. Embekke Devale is the southernmost of the three Western Temples from the Gampola period, the one closest to Gampola, which is the ancient Gangasiripura, which was the capital of Sri Lanka in the 14th centura. More precisely, it was the residential city of the Sinhalese kings, whose actual power was in decline those days.

|

Furthermore, there are facilities for Sinhalese pilgrims. Another workshop of a woodcarver can be found outside the hamlet, at the gravel road to the village of Embekke.

Names of Embekke and Kataragama and Gampola

"Embekke" is pronounced with a short "ae" at the beginning and stressed on the second syllable. Be aware, there are many different spellings of „Embekke“, as the first and second „e“ are actually pronounced „ae“ and the last „e“ is spelt (not pronounced) „a“ in Sinhala. Most common latinized spellings of the name are „Embekka“ and „Ambekke“, but in further literature you could also find „Embakka“ or „Ambakka“.

The name is derived from "Ann-bakka", which literally means "horn-big" in Sinhala. "Anbakka" is said to have been the former name of the place. The ancient name refers to one of the many local traditions of Embekke. In ancient times, an annual ritual called "Ankeliya" was celebrated in honor of the goddess Pattini. An extraordinarily big horn safekept in the nearby village played a crucial role in the ceremonies of this festival

The name is derived from "Ann-bakka", which literally means "horn-big" in Sinhala. "Anbakka" is said to have been the former name of the place. The ancient name refers to one of the many local traditions of Embekke. In ancient times, an annual ritual called "Ankeliya" was celebrated in honor of the goddess Pattini. An extraordinarily big horn safekept in the nearby village played a crucial role in the ceremonies of this festival

Legend of the Kataragama shrine of Embekke

the juvenile god Kataragama with his six heads and flanked by his two consorts

the juvenile god Kataragama with his six heads and flanked by his two consorts

All over Sri Lanka there are many temples dedicated to the major deity of the south of the island, Kataragama. He is identified with the northern Indian God of War, Skanda, and the Tamil shepherd deity, Murugan. Next to Kandy, Embekke is the most important Kataragama shrine in the hillcountry. According to the founding legend of Embekke, the construction of the temple has an intimate connection with the main temple of Kataragama in the pilgrimage site of the same name in the south of Sri Lanka, where the ever-young heroic god is believed to have settled down after his arrival from India.

The founding legend is narrated in a poetical work named Embekke Varnanawa, which is attributed to Delgahagoda Mudiyanse, an otherwise less known composer. The legend has it that Henakanda Bissobandara, one of the consorts of King Vikramabahu III, campaigned for the building of the temple. So the story goes:

The founding legend is narrated in a poetical work named Embekke Varnanawa, which is attributed to Delgahagoda Mudiyanse, an otherwise less known composer. The legend has it that Henakanda Bissobandara, one of the consorts of King Vikramabahu III, campaigned for the building of the temple. So the story goes:

The drummer Rangama, who lived in the hamlet of Aratthana, which was famous for its drummers and dancers, suffered from an almost incurable disease of the skin. As no medicine was helful, he went on a pilgrimage to the temple in Kataragama in the south of Sri Lanka. There he vowed to the God of Kataragama to perform rites with his drums at the temple annually. Miraculously, the skin disease was cured soon afterwards. For many years to come Rangama kept his promis and performed his pilgrimages to Kataragama each and every year. However, the long journey was not easy. When Rangama got old, he was increasingly incapable to walk that arduous path to a far-distance temple. On his last pilgrimage to Kataragama, he prayed to the god and confessed not eo be able to return as promised in the years to come. Deeply saddened about it, he returned home from Kataragama. But the following night the god appeared to him in a dream and revealed that a miracle would occur after a few days. Then he, Rangama, should walk to the place of this miracle and perform the drum ritual at that very spot. It happened that when a gardener tried to cut down a Kaduru tree in the flower garden of Queen Henakanda Bissobandara's flower, blood was pouring out from the tree instantly after the very first cut. When the drummer Rangana heard about it, he went into that flower garden and performed his rituals there, as the god had advised him to do, and he built a small wooden temple around the tree. A few days later King Vikramabahu in Gangasiripura came to know about it. He ordered the construction of a large temple with two upper floors and donated land and elephants to the new temple. The queen bequeathed her jewels to the temple. And ever since the drumming ritual has been performed every year in this new Kataragama Temple in Embekke. It is said that even today the descendants of that pious devotee Rangama are among the drummers that attend the annual festival.

History of the Embekke Devale

Theories on the origin of the wooden pillars and their carvings contradict each other. A first shrine has definitely been built at this site in the Gampola periody, see above. However, it‘s questionable whether the stone building of the main shrine behind the Digge is the original one from the 14th century. Even more unlikely is the common statement that hat the pillars of the Digge are from the Gampola period, too. Some claim, they were originally part of the ceremonial throne or audience hall in Gampola and later on they were removed from Gampola and reused in Embekke during the early modern Kandy period. But the said late medieval origin of the carvings is highly unlikely, as the dancers depicted on the panels wear typical costumes of the Kandy period and a horseman almost certainly represents a European dress, of which the Gampola artists of the Middle Ages could not have had any visual impression. In case all the pillars and their reliefs actually date back to one and the the same period, which is likely sue to their similar styles, or are even made by the same artist, as is often claimed, then they cannot have existed already at a palace of the kings of Gampola. The entire hall is most probably an edifice from the Kandy period, this is to say: a later addition or otherwise a replacement of an earlier hall. In fact, from the perspective of a lover of Sinhalese art, the carvings of Embekke should be considered to be the highlights of the Kandyan art of woodcarving, though they are found at a temple of the earlier Gampola period.

However, the carvings at the door of the Embekke Devale might be more ancient than those at the pillars of the drummers hall. If anything of today's structure, which is from the Kandy period, dated back the Gampola period, most likely this door would be a part of the original temple

So that later date of the pillar carvings – 17th or 18th century instead of 14th century – does not at all diminish the fame of the Embekke carvings. The quality of the woodcarvings far exceeds all other specimens found at other Kandyan-style pavilions. It‘s also possible that the Digge of Embekke is one of the earliest of its kind in the Kandy period and served as a kind of model for other wooden hypostyle halls of the Kandy kingdom. Indeed, it seems likely that the Embekke Digge is earlier than the audience hall of the Kandy kings found at the Tooth Temple.

The name of the artist of the Embekke carvings is given as Devendra Mulachari. In this case, the pillar decorations could be evene laterr, as an artist of that name lived in the early 19th century, he was the court architect of the last Kandy king Sri Vikrama Rajasingha. It was this Devandra Mulachari who designed the eye-catching octagonal porch of the temple of the tooth in Kandy. However, the Digge von Embekke shows absolutely no similarities with that late Kandyan style.

However, the carvings at the door of the Embekke Devale might be more ancient than those at the pillars of the drummers hall. If anything of today's structure, which is from the Kandy period, dated back the Gampola period, most likely this door would be a part of the original temple

So that later date of the pillar carvings – 17th or 18th century instead of 14th century – does not at all diminish the fame of the Embekke carvings. The quality of the woodcarvings far exceeds all other specimens found at other Kandyan-style pavilions. It‘s also possible that the Digge of Embekke is one of the earliest of its kind in the Kandy period and served as a kind of model for other wooden hypostyle halls of the Kandy kingdom. Indeed, it seems likely that the Embekke Digge is earlier than the audience hall of the Kandy kings found at the Tooth Temple.

The name of the artist of the Embekke carvings is given as Devendra Mulachari. In this case, the pillar decorations could be evene laterr, as an artist of that name lived in the early 19th century, he was the court architect of the last Kandy king Sri Vikrama Rajasingha. It was this Devandra Mulachari who designed the eye-catching octagonal porch of the temple of the tooth in Kandy. However, the Digge von Embekke shows absolutely no similarities with that late Kandyan style.

Structures of the Embekke Temple

|

The temple compound of the Embekke Devale is enclosed by a wall, as usual for larger Hindu temple compexes. The main entrance to the temple precincts is from the east. This is a common feature of sacred Hindu architecture, too. The gatehouse, which also serves as the ticket office today, is a small pavilion with ten pillars. It is a kind of wooden variant of a Gopuram, the latter being the Indian term for temple gates. More precisely, only the tiled roof is a wooden structure, whereas the pillars and walls are new and made of stone or even concrete.

|

Gopurams are the doorways in enclosure walls of Indian and Southeast Asian temples and can be very elaborate in southern India and Cambodia in particular. However, they are less important in classical Sri Lankan temple architecture and more often seen at Hindu Kovils of the Tamil minority than at the Buddhist Viharas and Devales of the Sinhalese.

There are various types of structures in the temple compound, including a kitchen. Entering from the east, there are two rice granaries to the left, just on the edge of the temple grounds. Like some granaries in Europe, they are placed on wooden supports to protect them from rats and mice. Astonishingly, such rice granaries within a temple complex are named with a Tamil word, namely "Kottara". The Sanskrit name would be "Ugrana".

By the way, the architectural type of stilt buildings became quite common in the sacred architecture of the Kandy period. In many temples of the Kandyan style it’s the main shrine, the so-called image house, that is set on wooden stilts. Such "raised" shrines, which are called Tampita or Tempita temples can be seen not only in the hillcountry but also in the plains of the North Western and North Central Provinces.

By the way, the architectural type of stilt buildings became quite common in the sacred architecture of the Kandy period. In many temples of the Kandyan style it’s the main shrine, the so-called image house, that is set on wooden stilts. Such "raised" shrines, which are called Tampita or Tempita temples can be seen not only in the hillcountry but also in the plains of the North Western and North Central Provinces.

The wooden Digge of the Embekke Devale

|

The most conspicuous building in the temple compound area is the Mandapa-like hall in front of the main shrine. It's completely made of timber, only placed on a stone terrace and with tiles as the roof. The hall is a so-called Digge, which is a Sinhala term meaning „drummers house“. Both „g“ of the word are pronounced: „Dig-Ge“, „Ge“ being a common abbreviation of „Gedere“ for „House“. Digges are a common feature of Kandyan-period temples in particulat, and it‘s likely that this hall is from that period, see below. A Digge can have two different functions.

|

At some temples it is a storeroom for musical instruments and chariots and guidons that are used during pageants at Perahera temple festivals. Such a kind of Digge is usually a walled room. But a Digge can also be a "drummers' hall" literally, a hall for rituals performed with musical instruments, the drum being the most common instrument in Sri Lanka. Such a Digge, as in the case of Embekke, is an open columned hall that can be seen – and heard - well by visitors of the temple standing in the court around the hall when the music is played during ceremonies.

The function as well the architectural concept of the Digge, particularly in the case of the Embekke Devale, corresponds roughly a Mandapa hall of a Hindu temple. It‘s a somewhat more airy vestibule in front of the main sanctuary, the latter safekeeping the icon of a god. The vestibule is used for the rituals of those who do not have access to the Holy of Holies, as access to the main sanctuary is reserved for priests. In Indian architecture, the hall and main sanctuary are usually clearly separated, each has its own roof, that of the main shrine being higher than that of the Mandapa. But most commonly they are made of the same material, either both are wooden structures or both are stone buidlins. In the case of Embekke, the comparatively inconspicuous main sanctuary, crowned by a higher tower, is made of brick, whereas the vestibule hall, the Digge, for drum ceremonies is made of wood, as said.

The Digge measures 16 m in length and 8 m in width and has 32 wooden pillars. This is the said main attraction of Embekke, as the shafts of these pillars and also some beams are decorated with the delicate wood carvings Embekke is famous for. The roof of the Digge has a feature that is quite imposing. Twentysix rafters slanting radially from above are fixed together at the very centre by a giant catch pin, which is known as „Madol Kurupuwa“.

|

It‘s worth taking a look at the roof of the Digge anyway, for eyample to take notice of the carved decorations on some of the beams and of almost all capitals.

Altogether 514 carvings are said to found in this Drummers‘ Hall. By far the most beautiful ones are the panels which are at eye level on the pillars. Of this panel type, there are 128 carvings in total, as each wooden pillar has such carvings at almost square panels on all four sides. The fame of Embekke is founded on the excellent quality of just these panels as well as on their abundance in variants.

|

Each panel is unique in design, although some motifs such as flowers or birds can be seen at more than one panel.

Various kinds of precious timber were used at the Devale of Embekke. The type of wood of the pillars of the Diffe is often given as sandalwood, a term commonly used to denote species from different plant families. The exact Sinhala name of the wood, Gammalu, stands for Pterocarpus marsupium. This tree does not belong to the sandalwood family Santalaceae but to the legume Fabaceae. Derived from the Nepalese name, “Bijasal” has become a term for this precious wood in European languages. In terms of trade, it belongs to the Padouk woods, named after a place in Burma. Padouk is considered to be just as good for furniture production as teak.

The wooden pillars of the Digge hall of the Embekke Devale stand on stone plinths. The lower section has a square groundplan, whereas the upper part of the pillars is formed by two octagonal sections, which are separated from each other by an almost cubic bulge. The lotus capitals correspond exactly those of the Kandyan style. Kandy capitals are always lush in appearance and have four half-open lotuses which are hanging downwards, facing the viewer.

By the way, that alternation of square and octagonal pillar sections is typical of the wooden buildings of the Kandy period, too. However, the columnar shape of the alternation of octagonal and square shaft sections as well as their distinctive cube-shaped bulges (with those almost square panels which can bear the main relief decoration) are features that are older than the early modern Kandy period and even older than the late medieval Gampola period. Rather, thise wooden pillars of the wooden halls of the Kandy period have their models in the stone pillars of the Polonnaruwa period. For example, this design can be seen in the vestibule of the so-called Yakfruit Temple of the Ridi Vihara in Reedigama. But these medieval stone pillars, in turn, are likely to have been replicas of wooden pillars, of which no examples have survived due to the perishable material. The reason for this hypothesis, that the (lost) prototypes of such „columns with a bulge“ were originally wooden – and then translated into stone and afterwards into wood again – is the design. The said bulges seem to have been joints of pillar sections or beams originally.

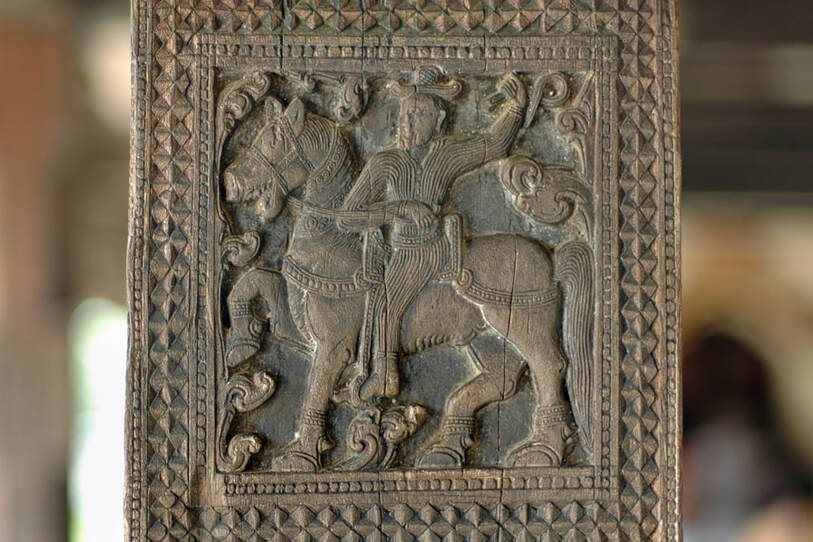

As said, the four sides of each distinctive cube, which looks like an angular bulge on the column shaft, are richly decorated. These cubic blocks carry the carvings for which Embekke is famous and which shall now be illustrated by showing some of the typical ornametal and most of the noteworthy figural designs:

Themes of the Embekke Woodcarvings

Floral ornaments

Most of the panels at the pillars show floral ornaments. The stalks and leaves intertwined in geometric patterns are vaguely reminiscent of arabesques. Many of them are Kalpalatas, mythical wish-fullfilling creepers, others are simply flowers depicted as large circular ornaments in the rectangular panels.

Animal depictions

The emblematic lion of the Sinhalese people can be seen at some of the panels, whereas elephant depictions are surprisingly rare at the Embekke Devale. Most of the animal depictions found in the Digge are birds, mostly peacocks and geese. Though all of them can be interpreted as mythical beings, they might also be just illustrations of ordinary birds knon from everyday life. Cocks with their long necks intertwined can be found more than once.

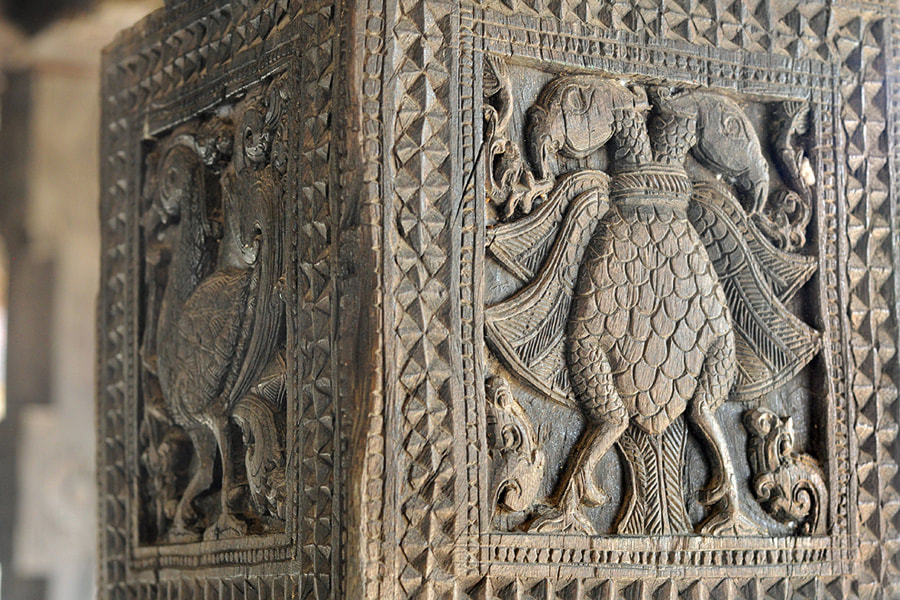

Mythical creatures

There can be no doubt, that some ot the depictions at the pillars of the Digge are mythical creatures not found in nature. Resembling the floral designs, the Kirtimukha mask can be seen in several varients. Kirtimukha, the "glorious face", is always engaged in swallowing vegetation. In the Hindu iconography, the "face of glory" in particular symbolizes the sun and time and the all-devouring deadly fire. It is the epitome of Shiva's destructive power as master of time. Though originally a symbol of Shivaism, it became a common feature in Buddhism, too, particularly at doors. But it's rarely found in Sri Lanka prior to the late Middle Ages. Similarly, the Gajasimha, a lion's body with an elephant's head, is a hybrid creature that can be found in Sinhala art only since the late medieval Yapahuwa period, though it is known in Indian and Southeast Asian art in much earlier periods. There is more than one Gajasimha shown at the Embekke panels. A theme from a later period of Indian art is the optical illusion of an elephant and bull sharing the same head. Carved at Indian temples already in the 12th century (Airatesvara temple near Kumbakunam in Tamil Nadu), it became a common subject of Indian art only in the early modern period, particularly in painted decorations of palaces. In Sri Lanka, such optical illusions known as Kunnarayas are decorative elements of the Kandy period.

Mythical birds

As mentioned above, birds are the animals most frequently depicted in Embekke carvings. Some of them are definitely not natural but mythical beings. The snorting peacock might represent a Makara. Though Makaras are usually depicted as crocodiles or dragons, they can also have the appearance of birds. Surprisingly, one of the hybrid creatures is a bird with an elephant's head, a combination rarely found in Asian art, though not completely unknown. Birds with trunks are already depicted the medieval Mon Art of northern Thailand and are today known as Hatsadiling. In contrast, the double-headed eagle, which can be seen in more than one varient in the drummers hall of Embekke, seems to be inspired by European heraldic symbols rather than by Asian prototypes.

Celestial beings

A bird with a human face is sometimes interpreted as Garuda. However, it's more likely it represents a Kinnara. A Kinnara is a a celestial musician, partly human, partly bird, though other types of hybrids are also known. Kinnaras are known from several Buddhists texts, including the canonical Jatakas and the Mahayanistic Lotus Sutra. Their female counterparts are Kinnaris, often depicted with human breasts. Kinnaras and Kinnaris are faithful couples without offspring, only devoted to each other, but they are benevolent towards human beings. Kinnaris are musicians at the Mountain of Gods in the Himalayas. Similarly, Apsaras are female dancers at the court of the gods.

Human life

The dancing figures at the Embekke Devale might be Apsaras of the gods or just human dancers of royal courts of the Kandyan period or both. Definitely, they wear Kandyan dresses. That some of the depictions at the Embekke Devale are not religious but secular can be seen from the fact that scenes from daily life can be found at the panels, too. A nursing woman carressed by a much smaller man could also refer to a mythological scene, but the chatting and arguing women are definitely a secular theme. The same subject is also known from the Panavitiya Ambalama near Kurunegala.

Depictions of fights

Another subject represented quite frequently at the Embekke Devale is fighting. If the lion attacking the elephant is a fighting seen, too, is debatable, as the elephant seems to be acquiescent and even amused. The scenes of human engaged on fights, however, are unambiguous. The wrestling scene shows the fighter in Kandyan dresses.

The native Sri Lankan martial arts are called Angampora and Ilangam, the former being unarmed, whereas the latter makes use of 32 different types of blades and swords. The most common of the traditional Sinhalese daggers is known as Piha Ketta. Sri Lanka's tradition of martial arts is said to be a tradition dating back even to the pre-Sinhalese period, when Yaksha demons inhabited the island. God Kataragama himself is considered to be a great Angampora fighter. When combating the Asura demons, he made use of his Angampora skills. Angampora, unarmed but potentially lethal by attacking the enemy’s nerve points and vessels, was part of the techniques used by the armies of Sri Lanka already in the medieval period and was still used to fight the Portuguese. The Kandy period marked the peak of martial art in Sri Lanka. Tournaments of two major competing schoolswere routinely fought in the presence of the king. According to Robert Knox, who spent many years in Kandy as a prisoner of war in the 17th century, large numbers of young men were trained in places called 'Angam Madu' and 'Ilangam Madu'. The Sinhalese martial art was prohibited by the British, who maimed practicioners by shooting into their knees and who also burnt down the practice huts. The decline under the British is the reason why Sri Lanka's martial art is less known than the south Indian Kalari. However, since independence some families that still practised secretely revived the tradition.

The native Sri Lankan martial arts are called Angampora and Ilangam, the former being unarmed, whereas the latter makes use of 32 different types of blades and swords. The most common of the traditional Sinhalese daggers is known as Piha Ketta. Sri Lanka's tradition of martial arts is said to be a tradition dating back even to the pre-Sinhalese period, when Yaksha demons inhabited the island. God Kataragama himself is considered to be a great Angampora fighter. When combating the Asura demons, he made use of his Angampora skills. Angampora, unarmed but potentially lethal by attacking the enemy’s nerve points and vessels, was part of the techniques used by the armies of Sri Lanka already in the medieval period and was still used to fight the Portuguese. The Kandy period marked the peak of martial art in Sri Lanka. Tournaments of two major competing schoolswere routinely fought in the presence of the king. According to Robert Knox, who spent many years in Kandy as a prisoner of war in the 17th century, large numbers of young men were trained in places called 'Angam Madu' and 'Ilangam Madu'. The Sinhalese martial art was prohibited by the British, who maimed practicioners by shooting into their knees and who also burnt down the practice huts. The decline under the British is the reason why Sri Lanka's martial art is less known than the south Indian Kalari. However, since independence some families that still practised secretely revived the tradition.

Stick dance

|

Though looking like a sword combat, this scene at a beam is not a fight but a dance. It's the traditional Sinhalese stick dance known as Lee Keli Natuma, as can be seen from the crossing of the sticks in the back of the dancers. In Lee Keli, each dancer has two sticks mutually used to generate rhythmic sounds. Both male and female dancers can participate. The stick dance popular in all parts of the island, it's performed particularly during festivals celebrations.

|