Situlpahuwa, also spelt Sithulpahuwa or Sithulpawwa, is situated 18 km east of the pilgrimage site Kataragama amidst the jungles of Yala National Park. Situlpahuwa is definitely a sight to see for those travellers in southern Sri Lanka who are interested in historical sites.

Content of our Situlpahuwa page:

Sithulpahuwa, often referred to as Chitthala Pabbhata in the ancient chronicles, was a major monastery of the southern region then called Rohana. Situlpahuwa is a highly likeable archaeological site due to the natural setting in between two neighbouring rocky ridges, which can be climbed and offer perfect views to the surrounding wilderness of Yala. Situlpahuwa has excavated temples as well as monastic caves and also some remarkable ancient statues and inscriptions. It’s not an unknown place off the beaten path. Nevertheless, the lovely site not yet overcrowded. That’s why a visit of this multifaceted and picturesque archaeological site can be highly recommended to guests who spend a night or two in the areas of Kataragama or Tissamaharama or Kirinda Beach.

Name of Sithulpahuwa

In the ancient chronicles, the monastery today known as Sithulpahuwa is mentioned quite frequently under the name Chittalapabbata. The modern Sinhala name of the place is actually derived from that ancient Pali term, which literally translates to "Peace of Mind Hill".

Be aware, there are many different latinised spellings of Sithulpahuwa such as Situlpahuwa, Situlpahuva, Sithulpawwa, Situlpawu or Sithulpahu etc.

Location of Sithulpahuwa

Administratively, the archaeological and pilgrimage site of Sithulpahuwa is administratively belongs to the area of Yala National Park. However, travelers usually do not visit it on a safari, but it can be reached via a sandy track from Kataragama, without national park ticket fees and without the obligation to use a jeep with a ranger.

Significance of Sithulpahuwa

Sithulpahuwa is not only an important Buddhist sanctuary and pilgrimage site again but one of the historically most important sites and a highlight of heritage tours in the south of Sri Lanka. Sithulpahuwa is a typical example of what makes Sri Lanka‘s ancient sites so attractive: works of art embedded in a charming scenery. Two bright white restored dagobas on granite rocks are excellent vantage points overlooking the entire Block 1 of Yala National Park, with the ocean in the background. In between the rocks are remnants of monastic architecture from the Anuradhapura period and typical Buddhist caves and Mahayana Buddhist sculptures and - most interestingly for historians - a total of 60 historical inscriptions. They are prove of the importance of this large monastery, which had played a major role in the ancient Rohana Principality since the second century BC. All in all, no other archaeological site in the south offers such a comprehensive impression of the ancient monastic culture of Sri Lanka as Sithulpahuwa.

When visiting the south of Sri Lanka, which is known as Rohana in the Pali language of the chronicles in antiquity and as Ruhunu in modern Sinhala, the remnants of the capital of this region can be seen in Tissamaharama, the most extensive archaeological site is the Ramba Vihara, the best-preserved monastic complex with a systematic layout is the Magul Mahavihara of Lahugala, Buduruwagala has the most rock sculptures and the largest single one of the entire island, the beautiful freestanding statues are those of Maligawila, by far the largest stupa is in Yudaganawa near Buttala, and last not least the by far most impressive monastic caves can be seen at Mulkirigala Rock. However, there is reason to claim Sithulpahuwa to be the most excellent heritage attraction of the south at all, because it‘s Rohana‘s only ancient site that combines all typical elements of ancient Sri Lanka at only one place, stupas, caves, sculptures. Situlpahiwa is, so to speak, the most complete ancient monastery in Rohana. And it was probably the most important monastery in the south during the Anuradhapura period. In addition, the setting is the solitude of a wonderful a national park. That alone makes a visit of Sithulpahuwa worthwhile.

History of Sithulpahuwa

|

Chittalapabbata, the ancient Sithulpahuwa, is considered to be a founding of no less than Kavantissa (Kakavanna Tissas), whi reigned in the south around 200 B.C. and is most famous for being the father of a rebellious son, Dutthagamani, who restored a Buddhist kingship in Anuradhapura and thereby became the national hero of the Sinhalese. Even though Sithulpahuwa was once not as remote as it seems to be today, it was well outside the capital city of Rohana. In this respect, it might be compared to Mihintale, which is in a distance to Anuradhapura. However, there is a difference. It‘s likely that Sithulpahuwa was the largest and most important monastery of the southern prinicipality at all, whereas the the three largest monasteries of the Anuradhapura Kingdom were situated within the capital. 12,000 monks are said to have lived here at the same time. This is obviously a gross exaggeration, as the largest monastery in Sri Lanka - the Abhayagiri in Anuradhapura - in its heidays housed a maximum of 7000 monks, which is impressive enough.

|

It might come to a surprise that the area of today's Yala National Park was not a wilderness in antiquity. That this region was far less lonesome in the Anuradhapura period is proven by the aforementioned high number of historical inscriptions. Even today's visitor also gets an impression of the heritage of this region when driving from Tissa or Kataragama to Yala, as smaller excavations on the way, including a stupa, will be passed on the way.

In particular, the contrast between the white stupa and the dark gray rock and a pond at its feet looks like a miniature version of the Sithulpahuwa site. |

Overall, however, the hills of Sithulpahuwa have the unusually high number of 160 rock shelters that served as monk's caves, some of them large enough to accommodate several monks.Despite its size and significance, Sithulpahuwa did not lose its reputation of great holiness as an abode of reclusives. 1000 monks are said to have attained Nirvana here, i.e. to have become Buddhist saints.

An Ancient Sithulpahuwa Legend & What it tells about Buddhism

In addition to the chronicles, the commentaries on the Holy Scriptures, which were also written in Pali, repeatedly mention Chittalapabbata and tell a kind of Acts of the Saints about its monks, such as this one:

A monk and his pupil once lived in the capital of Ruhana. The old monk saw that his disciple was on the verge of enlightenment when the latter revealed his ambition to leave the order, because he disliked the life of the monks in the town. The old monk agreed that the pupil should take off the robe and become a layman, but only after he had accompanied him to Chittalapabbata, where there was enough water for a cleansing bath. This way the old monk hoped to buy time that his pupil could attain Nirvana in the meantime. But when they arrived in Chittalapabbata alias Sithulpahuwa, the young disciple was still not enlightened, and so the old monk wasted more time by asking him to prepare a cave for him, which he himself was too weak to do, and he should do so condiderately and mindfully. When the young monk had carried out this service conscientiously, the old monk advised him that, before leaving, he should lie down and take a rest after all the work he had done. So the young monk went calmly and observantly to his little hut and rested there for one night. But the next morning he had developed his mindfulness so completely and perfectly well, that he attained enlightenment. This way, the old wise monk had achieved his goal.

The legend is a vivid example of the specific path of enlightenment that is tought in Buddhism. What is given here as "mindfulness" is actually a translation of the Pali word "sati" (Sanskrit: "smriti"), which denotes the seventh item of the eight-fold path to awakening. In the sacred scriptures of Buddhism Sati is actually the core element of the path to enlightenment in the sense that is more stressed than in other contemporary Indian practices. Sati consists in constantly focusing on what one is just doing at any given point in time. What is done momentarily can be such different activities as preparing an accommodation or going to bed. Sati simply means being fully focused on what‘s going on. By practicing this kind of meditation in ordinary activities, the student attains extraordinary perfection of this focussed mindset. The clever old monk not only bought some more time again and again, but what he was actually doing is teaching the right meditation technique.

One characteristic aspect of the Buddhist understanding of awakeing is that it‘s not a spectacular event, but very calm and continuous. The Buddhist enlightenment is neither associated with ascetic or ritual or gnostic achievements as in esoteric circles, nor with an engagement in a dialogue with a higher authority or with an externally imposed change of mind through a gift of grace as in the Christian redemption dramaturgy. No higher power intervenes on the Buddhist path of salvation, but something happens of its own accord, for which other beings can only create most favorable conditions. The polemical Christian interpretation, which is extremely widespread in Western literature on Buddhism, that this is "salvation from one's own strength" - that is: a kind of hubris, since such strength can only come from a perfect authority - completely misunderstands the crucial point.

In fact, in Buddhism Sati practitioners cannot have their own strength and succeed by their own efforts at all. They cannot, because they are without a soul. This is the central Buddhist teaching of Anatta (Sanskrit: Anatman), which translates to „non-self“. To put it in other words: In a Buddhist understanding of the world there is nothing like “on one‘s own”, the idea of a self being the source of anything is a deception. Rather, Budddhist interpret the world a realm of interaction. The momentum that leads to salvation in Buddhism - and which in fact has nothing to do with superordinate world authorities - is not owned by a meditator, but it‘s due to the path of meditation. Whoever practices Sati is practicing its perfection (the perfection of Sati and not the perfection of one‘s own self, which from a Buddhist point of view is just a meaningless goal, a supposed solution to a problem only created by oneself and not really existent). From a Buddhist point of view, the Christian theology of grace turns out to be the erroneous assumption that salvation is about oneself. This state of mind – salvation is something concerning the very essence of one‘S pwn person - turns out not only to be a misunderstanding of what salvation is about but actually a hindrance on the path. A Christian usually is full of disdain for the Buddhist way of salvation without any reference to or intervention from supreme beings. The Buddhist is simply amused about the Christian way of salvation circling around a self at all. However, there is significant difference: Buddhists only see Christians trapped in a mistake, that of misunderstanding, but unlike Christians, who see those who don‘t see any value in a heavenly gift of salvation, Buddhists do not mingle the rejection of the true path of salvation with a moral flaw or something like a sin.

One characteristic aspect of the Buddhist understanding of awakeing is that it‘s not a spectacular event, but very calm and continuous. The Buddhist enlightenment is neither associated with ascetic or ritual or gnostic achievements as in esoteric circles, nor with an engagement in a dialogue with a higher authority or with an externally imposed change of mind through a gift of grace as in the Christian redemption dramaturgy. No higher power intervenes on the Buddhist path of salvation, but something happens of its own accord, for which other beings can only create most favorable conditions. The polemical Christian interpretation, which is extremely widespread in Western literature on Buddhism, that this is "salvation from one's own strength" - that is: a kind of hubris, since such strength can only come from a perfect authority - completely misunderstands the crucial point.

In fact, in Buddhism Sati practitioners cannot have their own strength and succeed by their own efforts at all. They cannot, because they are without a soul. This is the central Buddhist teaching of Anatta (Sanskrit: Anatman), which translates to „non-self“. To put it in other words: In a Buddhist understanding of the world there is nothing like “on one‘s own”, the idea of a self being the source of anything is a deception. Rather, Budddhist interpret the world a realm of interaction. The momentum that leads to salvation in Buddhism - and which in fact has nothing to do with superordinate world authorities - is not owned by a meditator, but it‘s due to the path of meditation. Whoever practices Sati is practicing its perfection (the perfection of Sati and not the perfection of one‘s own self, which from a Buddhist point of view is just a meaningless goal, a supposed solution to a problem only created by oneself and not really existent). From a Buddhist point of view, the Christian theology of grace turns out to be the erroneous assumption that salvation is about oneself. This state of mind – salvation is something concerning the very essence of one‘S pwn person - turns out not only to be a misunderstanding of what salvation is about but actually a hindrance on the path. A Christian usually is full of disdain for the Buddhist way of salvation without any reference to or intervention from supreme beings. The Buddhist is simply amused about the Christian way of salvation circling around a self at all. However, there is significant difference: Buddhists only see Christians trapped in a mistake, that of misunderstanding, but unlike Christians, who see those who don‘t see any value in a heavenly gift of salvation, Buddhists do not mingle the rejection of the true path of salvation with a moral flaw or something like a sin.

An Sithulpahuwa Episode in the Classical Visuddhimaggha Commentary

The Visuddhimaggha, the classical compendium of Theravada Buddhism, contains the following episode about Sithulpahuwa and salvation:

An Indian named Visakha came to Sri Lanka to join the Buddhist Order. After five years of training in Anuradhapura, he had become an exemplary and benevolent monk. The new Bikkhu then went on a journey and spend four months in each monastery before moving on. On the way to Chittalapabbata Visakha arrived at a fork and did not know which way to take. But a god from the nearby rocks revealed the direction to him. After four months in Chittalapabbata, Visakha heard someone crying in the night before his departure. When he asked who was crying, he got the answer: "I am the one, the god Maniliya." "And why are you crying?" The deity in a tree responded: "Because you will go away tomorrow." The monk asked: "Why should my moving on be important to you?" "Because even we, the gods, ceased quarreling since you came here." So Visakha agreed to stay in Chittalapabbata for another four months. But when he was about to leave after that second period, the same happened again. And the extensions were repeated so many times that when Visakha finally attained enlightenment, he was still in Chittalapabbata.

What to see in Sithulpahuwa

When arriving at the large new pilgrim parking lot at the foot of Sithulpahuwa, the first impression of the heritage site might be disappointing, as concrete buildings and souvenir stalls are predominant. After all, those small pilgrim restaurants invite you to enjoy a local herbal tea. However, the main attraction is the excavation a little bit hidden on the other side of the nearby hill, which is crowned by a large white dagoba.

There is a medium-sized white dagoba named Maha Situlahuwa Stupa atop the steep granite rock near the parking lot. The stupa platform can be easily reached via two stairways. The core of the stupa dates back to the 3rd century, but the pearly-white appearnce is the result of a restoration in the 20th century.

There is a medium-sized white dagoba named Maha Situlahuwa Stupa atop the steep granite rock near the parking lot. The stupa platform can be easily reached via two stairways. The core of the stupa dates back to the 3rd century, but the pearly-white appearnce is the result of a restoration in the 20th century.

That the original dagoba was presumably of a flatter shape can still be seen at two smaller brick stupas a little further below but still close to the summit terrace. It is popularly believed that the remains of the Buddha lie beneath the main stupa and the remains of two of his main disciples under those secondary stupas.

|

The rocky summit is a vantage point with an excellent panoramic view of the entire Yala National Park.

Above all, the historical core area of Chittalapabbata can be overlooked from here, as it is located in between the two distinctive parallel granite ridges. Apart from the ruins, there is a small reservoir in the valley between the two rocks. |

Towards the southwest there is another peak, which can be seen in a far distance. It‘s a granite rock known as Akasachetiya, which is already mentioned in the chronicles. The name literally translates to "heavenly stupa". The 2000 year old dagoba on top of it is still in its original condition. On that distant rock there was another ancient monastery of forest monks. Today, it‘s even more lonesome and pristine than Sithulpahuwa. Some hikers visit the place. But the ascent is not possible without climbing. And the path should not be gone without a local ranger, as the elephants and leopards and bears roam in this area.

At the foot of the rock of Sithulpahuwa is a new white construction, which is probably designed as a terrace for a Bo-tree. Sri Lanka's pilgrimage sites tend to “upgrade” the natural beauty of the place by new buildings. This might be disturbing form a conservationist perspective. However, one should keep in mind that Sithulpahuwa is not only an archaeological but also a religious site. It is not only a present-day phenomenon, it has been a common practice throughout the centuries to extend of even redesign ancient places in the style of the time.

Just to the northwestern of the rock is a large columned hall. The large pillars are from the Anuradhapura period. This edifice was the chapter house of the historical Chittalapabbata monastery. The groundplan, though smaller in size and number of columns, seems to be insoired by the famous Lohapasada of the Mahavihara monastery in Anuradhapura. This is to say, it‘s likely that the stone pillars once carried upper floors made of timber.

Just to the northwestern of the rock is a large columned hall. The large pillars are from the Anuradhapura period. This edifice was the chapter house of the historical Chittalapabbata monastery. The groundplan, though smaller in size and number of columns, seems to be insoired by the famous Lohapasada of the Mahavihara monastery in Anuradhapura. This is to say, it‘s likely that the stone pillars once carried upper floors made of timber.

At the foot of the rock, very close to the ascent to the stupa, is one of the numerous rock inscriptions of Sithulpahuwa. It‘s a custom of pilgrims to throw coins upon that tablet. This males sense in a way, as that the inscription refers to gifts of money. The text reads: “King Gamani Abhaya, son of the great King Tissa and grandson of the great King Vasabha, donates the two Kahapanas that he received daily from the High Court of Dubala, Yahatagama and Akujamahagama, in order to consistently provide medicine worth two Kahapanas for the community of monks of Chittalapabbata ”.

Click here for More Details on Situlpahuwa Inscriptions

The pious work mentioned in the inscription is evidence of the early use of the ancient Indian silver coins called Kahapanas, which also have been excavated. The minting system in India was based on the Roman model. Although Kahapanas are said to have also been made of gold or copper, only silver Kahapanas have been excavated so far. Theay are called "Eldings" by the British. The amount of silver of one Kahapana is about 4 grams. Silver was a trade item from the Mediterranean region for which there was a stron demand on the subcontinent.

Due to the style of the fonts, which are a somewhat later type of Brahmi, the inscription can be dated to the second century AD. The king's name is also identifiable: King Gamani Abhaya. However, this does not necessarily refer the famous Anuradhapura king Vattagamani Abhaya of the first century BC, as „Gamani“ was a common name and „Abhaya“ is also known from other texts even in India. The name of the grandfather is given in this inscription as „Vasabha“, whereas Vattagamani Abhaya‘s grandfather was Kavantissa, the abovementioned king of Rohana. Rather, Vasabha was the founder of the Lambakanna dynasty in Anuradhapura and reigned in the 1st century AD. The grandson of Vasabha meant in this inscription is likely the king who is popularly called Gajabahu ("elephant arm"), who reigned in the 2nd century AD.

Another inscription in Sithulpahuwa attests an astonishing practice: It names fines for crimes such as adultery. As antiquated as this may seem today, in other ancient cultures such as the Jewish adultery was punishable by death. That corporal punishment was replaced by fines in Sri Lanka already in antiquity is almost certainly to be attributed to the Buddhist religion of the island nation. By the way, this historical record contradicts claims that Asian traditions are less concerned about human rights. Reductions or even abolition of physical punishments and death penalty are also known from ancient India.

There are two more large inscriptions at the northern side of the ascent, they are attributed to the first century. One makes mention of King Ilanaga. Both inscriptions are valuable historical sources, revealing facts about the economic life of the monasteries in the Anuradhapura period. The king donated villages to the monasteries, or more precisely: their agricultural land, from which the taxes no longer were collected for the king but to the Buddhist Order. From then on, the paddy farmers even had to pay water fees to the Buddhist monastery, according to the second inscription. This means, the temple administered the irrigation system of a specific region, irrigation being the crucial element of the ancient Sinhalese civilisation.

Another inscription on the same rock dates back to King Vasabha, the abovementioned founder of the Lambakanna dynasty. Vasabha was not the first king who constructed tanks but the first one doing this on a large scale, making him one of the important persons of the island‘s history. Remarkably, the mentions a female person, a princess, as donator. Women highlighted as donors, however, is more than once found in Sri Lanka‘s ancient records.

Due to the style of the fonts, which are a somewhat later type of Brahmi, the inscription can be dated to the second century AD. The king's name is also identifiable: King Gamani Abhaya. However, this does not necessarily refer the famous Anuradhapura king Vattagamani Abhaya of the first century BC, as „Gamani“ was a common name and „Abhaya“ is also known from other texts even in India. The name of the grandfather is given in this inscription as „Vasabha“, whereas Vattagamani Abhaya‘s grandfather was Kavantissa, the abovementioned king of Rohana. Rather, Vasabha was the founder of the Lambakanna dynasty in Anuradhapura and reigned in the 1st century AD. The grandson of Vasabha meant in this inscription is likely the king who is popularly called Gajabahu ("elephant arm"), who reigned in the 2nd century AD.

Another inscription in Sithulpahuwa attests an astonishing practice: It names fines for crimes such as adultery. As antiquated as this may seem today, in other ancient cultures such as the Jewish adultery was punishable by death. That corporal punishment was replaced by fines in Sri Lanka already in antiquity is almost certainly to be attributed to the Buddhist religion of the island nation. By the way, this historical record contradicts claims that Asian traditions are less concerned about human rights. Reductions or even abolition of physical punishments and death penalty are also known from ancient India.

There are two more large inscriptions at the northern side of the ascent, they are attributed to the first century. One makes mention of King Ilanaga. Both inscriptions are valuable historical sources, revealing facts about the economic life of the monasteries in the Anuradhapura period. The king donated villages to the monasteries, or more precisely: their agricultural land, from which the taxes no longer were collected for the king but to the Buddhist Order. From then on, the paddy farmers even had to pay water fees to the Buddhist monastery, according to the second inscription. This means, the temple administered the irrigation system of a specific region, irrigation being the crucial element of the ancient Sinhalese civilisation.

Another inscription on the same rock dates back to King Vasabha, the abovementioned founder of the Lambakanna dynasty. Vasabha was not the first king who constructed tanks but the first one doing this on a large scale, making him one of the important persons of the island‘s history. Remarkably, the mentions a female person, a princess, as donator. Women highlighted as donors, however, is more than once found in Sri Lanka‘s ancient records.

Turning left at those inscriptions and proceeding in the direction of the reservoir, the visitor arrives at Situpahuwas largest rock shelter used as a shrine room. Such abris are usually called “caves” in Sri Lakja. A newly whitewashed outer wall has turned this rock shelter into a closed shrine room for the veneration of a long recumbent Buddha with two disciples at his feet. The sculptures are modern, but the bricks forming the core of the reclining Buddha might be from a much earlier period.

For a lover of ancient Buddhist art, however, the two statues in front of the cave, now protected by a pavilion, are much more interesting. They depict two Bodhisattvas, saviours venerated in Mahayana Buddhism. The statues are dated to about the eighth century. This corresponds the late Anuradhapura period. It‘s not inscriptional evidence but the art of the period that indicated that Mahayana Buddhism played an important role in southern Sri Lanka during this period, as most sculptures show Mahayanistic influence. Both statues are without arms now, also one head is missing. The sculpture with head probably represents the Avalokiteswara, whereas the one without a head could be the Bodhisattva Maitreya, who is venerated in both Theravada and Mahayana. The Avalokiteshwara statue is considered to be one of the highest quality that were found in ancient Rohana.

Below the rock that carries the stupa and shelters the recling Buddha are remnants of the foundation walls of two other ancient buildings. The larger one, which is closer to the rock, was a classical Sinhalese shrine for the veneration of a Buddha statue. Such a so-called image house (Pilimage in Sinhala) had a wider main shrine room for the statue and a slightly more narrow vestibule for the layman attending ceremonies.

There is an almost plain moonstone in front of the entrance to the said vestibule there is a relatively plain moonstone. It seems to be nothing special, but this specimen is already of considerable size and apparently was slightly carved. What is out of the scope of the usual temple entrance scheme indeed is that there is a second moonstone to the opposite direction on the inside of the threshold.

The smaller structure closer to the reservoir has an almost square floor plan, with a smaller square made of brick in the very centre. The latter most probably formed the terrace of a Bo-Tree. This is to say, the temple was a Bodhigare, a shrine for tree worship. The big monolith that lies in front of the structure, towards the pond, is quite interesting. It is an Asana, a throne, that only symbolically represents the presence of the Buddha – just like a Bo-treebaum - without any depiction, there is no statue on it. Buildings with such a stone throne demonstratively left empty are referred to as „Asanaghara“ in Sinhalese monatic architecture. The term translates to „seat house“ or „throne house“, whereas „Bodhigara“ means „enligthenment house“ or „tree house“.

Asanas representing the Buddha are symbols that were already used in pre-Christian centuries in India, whenn Buddha statues had not yet been introduced. It‘s highly likely that the “stone throne” of Situplahuwa is a monolith that was cut and brought to the sanctuary already in the early Anuradhapura period. The abovementioned compendium of Theravada teachings composed by Buddhaghosa, the Visuddhimagga, handed down many local folk tails from that early period. One of those legends referring to Sithulpahuwa tells of another type of meditation, one that, in its emphasis on instantaneousness and by its brevity and conciseness, almost appears like a Japanese Haiku of Zen Buddhism: „A monk sees a flower placed on the Asana and thus perfects his meditation.“ This Asana mentioned in the Visuddhimagga can definitely be the preserved large stone, as no other Asana has been found in Sithulpahuwa.

Below the rock that carries the stupa and shelters the recling Buddha are remnants of the foundation walls of two other ancient buildings. The larger one, which is closer to the rock, was a classical Sinhalese shrine for the veneration of a Buddha statue. Such a so-called image house (Pilimage in Sinhala) had a wider main shrine room for the statue and a slightly more narrow vestibule for the layman attending ceremonies.

There is an almost plain moonstone in front of the entrance to the said vestibule there is a relatively plain moonstone. It seems to be nothing special, but this specimen is already of considerable size and apparently was slightly carved. What is out of the scope of the usual temple entrance scheme indeed is that there is a second moonstone to the opposite direction on the inside of the threshold.

The smaller structure closer to the reservoir has an almost square floor plan, with a smaller square made of brick in the very centre. The latter most probably formed the terrace of a Bo-Tree. This is to say, the temple was a Bodhigare, a shrine for tree worship. The big monolith that lies in front of the structure, towards the pond, is quite interesting. It is an Asana, a throne, that only symbolically represents the presence of the Buddha – just like a Bo-treebaum - without any depiction, there is no statue on it. Buildings with such a stone throne demonstratively left empty are referred to as „Asanaghara“ in Sinhalese monatic architecture. The term translates to „seat house“ or „throne house“, whereas „Bodhigara“ means „enligthenment house“ or „tree house“.

Asanas representing the Buddha are symbols that were already used in pre-Christian centuries in India, whenn Buddha statues had not yet been introduced. It‘s highly likely that the “stone throne” of Situplahuwa is a monolith that was cut and brought to the sanctuary already in the early Anuradhapura period. The abovementioned compendium of Theravada teachings composed by Buddhaghosa, the Visuddhimagga, handed down many local folk tails from that early period. One of those legends referring to Sithulpahuwa tells of another type of meditation, one that, in its emphasis on instantaneousness and by its brevity and conciseness, almost appears like a Japanese Haiku of Zen Buddhism: „A monk sees a flower placed on the Asana and thus perfects his meditation.“ This Asana mentioned in the Visuddhimagga can definitely be the preserved large stone, as no other Asana has been found in Sithulpahuwa.

The picturesque pond in between the two rocks of Sithulpahuwa is man-made. Be aware, that it is inhabited by crocodiles. Near the pond are further caves or rock shelters that once served as simple accommodation of the highly respected forest monks of Chittalapabbata. On the other side of the pond, one can climb up on the other side to the second rock carrying the second white Dagaba of Sithulpahuwa. It‘s called Kuda Sithulpahuwa Stupa, which just means "Little Sithulpahuwa Stupa". The platform of this second white Dagaba is another good vantage point. Despite the name „little“, the second rock is even a little bit higher than its neighbour. In the vicinity of the rocks are some more remnannts of the ancient Chittalapabbata scattered in the jungle. It is estimated that 80% of the historical monastery that is still hidden in the jungle.

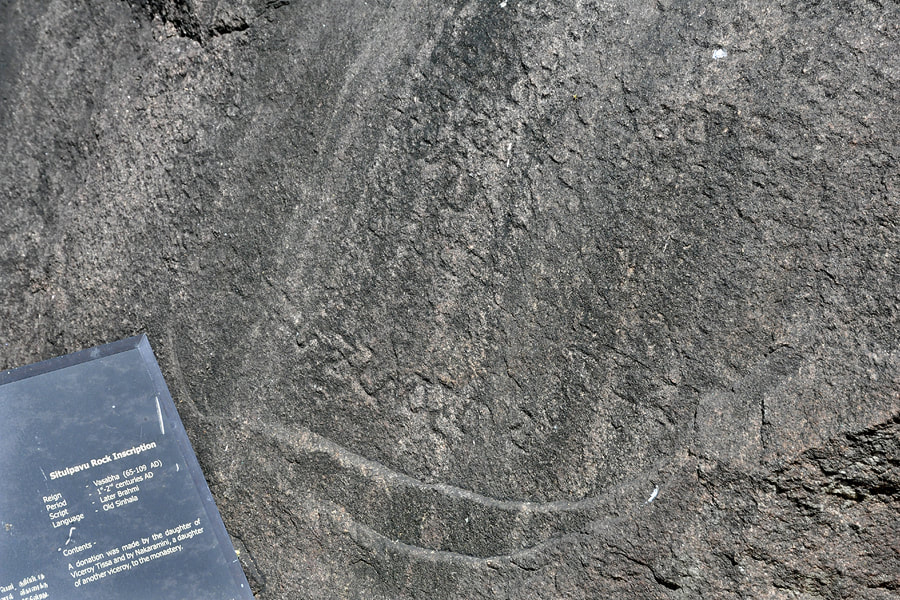

In the valley of the pond is another rock inscription, provided with an explanation board. It is another of the inscriptions of King Vasabha from the 1st century and it also mentions a female donator.

The view from the pond back to the main rock and the excavation area in front of it is a pleasant one, as this is still a peaceful place undisturbed by the stalls and parking lot at the other side of the rock. This area leaves an impression of the tranquility that once attracted reclusives to settle down in Sithulpahuwa.

The view from the pond back to the main rock and the excavation area in front of it is a pleasant one, as this is still a peaceful place undisturbed by the stalls and parking lot at the other side of the rock. This area leaves an impression of the tranquility that once attracted reclusives to settle down in Sithulpahuwa.

In the valley of the pond is another rock inscription, provided with an explanation board. It is another of the inscriptions of King Vasabha from the 1st century and it also mentions a female donator.

The view from the pond back to the main rock and the excavation area in front of it is a pleasant one, as this is still a peaceful place undisturbed by the stalls and parking lot at the other side of the rock. This area leaves an impression of the tranquility that once attracted reclusives to settle down in Sithulpahuwa.

The view from the pond back to the main rock and the excavation area in front of it is a pleasant one, as this is still a peaceful place undisturbed by the stalls and parking lot at the other side of the rock. This area leaves an impression of the tranquility that once attracted reclusives to settle down in Sithulpahuwa.